The Punishment of Virtue (24 page)

Read The Punishment of Virtue Online

Authors: Sarah Chayes

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: Cleaning an air filter on the Kabul to Kandahar road.

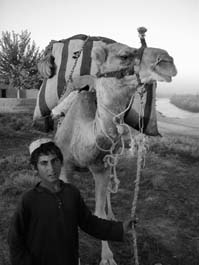

A nomad boy on the move, Helmand Province.

Three girls at a gas station on the Kabul to Kandahar road.

A young shepherd across the street from the Arghand workshop in Kandahar.

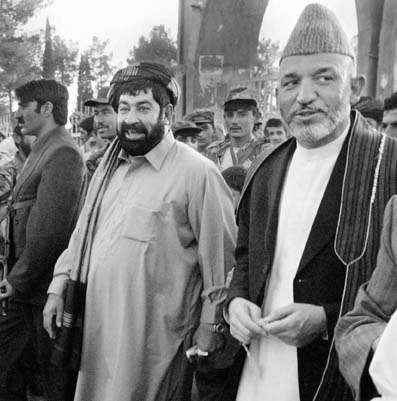

President Hamid Karzai (right) and Gul Agha Shirzai.

(AP I

MAGES

)

burqas

, and demanded that I take their picture. “Take it to America!” they cried. A revolutionary gesture.

Muhammad Akrem Khakrezwal in July 2003.

I later learned Civil Affairs had been told that the army did not like ACS's views, and they were not to have anything to do with us. Then when the units rotated and the base came under new command, I was issued a pass and could drive on and off unchallenged. Such was the bewildering lack of system that seemed to characterize much of the army's activities in Kandahar. Apparently, each incoming captain liked to leave his mark by making a new set of rules. Sort of like a dog peeing on a post.

At the gate, the one constant was Shirzai's insolent young men with their dark glasses and newly minted pickup trucks roaring through.

When President Karzai gave command of the provincial security forces to Mullah Naqib and Akrem's Alokozais as a check on Shirzai's power, one obvious move remained to Shirzai on the Kandahar chessboard, and he made it. He formed his own personal security forces. Thanks to funding provided by the U.S. army, Shirzaiâwho before the war had had to scrounge for followersâwas able to recruit and deploy two extralegal military units.

Nazmi Khass

, or the Special Force, was housed in palatial new barracks on the main road into town. This was the unit that competed with Akrem's police inside Kandahar proper, setting up its own checkpoints around town and coming to blows with the legitimate police. The second group of fighters was stationed out at the airport under the command of Gul Agha's brother Razziq. They continued to serve as U.S. proxies in the ongoing “war on terror.”

Technically, their role was a military one. They were charged with providing outer rim security for the U.S. base and with joining U.S. troops on missionsâboth combat and assessment visitsâaround the countryside. In practice, just the way engineer Abdullah made himself indispensable to me, Razziq and his colleagues saw to the grateful Americans' every need. And before long, the U.S. forces were helplessly wrapped inside the Shirzais' friendly bear hug.

The troops needed pickup trucks? Shirzai provided them, on lease, at rates so high the army could have paid for the truck outright within five or six months. The base needed gravel? Shirzai crushed it at his new facility or bought it from our friend the quarryman at $8 a tractor load and charged the U.S. Army $100. The Americans wanted to make a contribution to the local economy by hiring local labor for menial work around the base? The Shirzais provided the workers, then extorted a quarter of their daily wage in kickbacks. A thousand laborers on base racked up $2,000 a day for the Shirzais. And the employees, grateful anyway, were almost all Shirzai's Barakzais. In assorted contracts with the two commanders of this militia, the United States paid out almost $100,000 to each per month. And that's without the perks: the free cases of soft drinks, the PX privilegesâor the inestimable power and prestige this relationship with the Great Power of the day afforded these gunmen on the local scene.

1

The outcome of most contests is determined by terrain, and the Americans had surrendered a choice position to Gul Agha Shirzai. “Outer rim security” meant manning Gate 1, the gate between the golf balls, behind the grinning MiG. By controlling the outer gate, Shirzai's men in effect controlled access to the base. No competitor could even approach the Americans to offer a better deal on goods or services. The consequences of this monopoly were not restricted to the waste of taxpayer money. The damage went to the core of the U.S. mission in Afghanistan.

When U.S. Army Civil Affairs bid out contracts for a reconstruction projectâa village well or school, for exampleâthe bidders' conferences were held at Razziq Shirzai's compound. Few who were not Razziq's friends got inside the gate. That meant the local contractors being subsidized in the interests of capacity and relationship building were all in Shirzai's orbit. Since the governor's suggestions for reconstruction projects were also largely followed, it seemed to most Kandaharis that the primary mission of U.S. troops in Kandahar was to service Gul Agha Shirzai and his Barakzai tribe.

During one of our chats in his cozy receiving room, Akrem put it to me this way: “The other tribes are frustrated, and they're starting to pull away.” We were discussing some intensive political activity Shirzai had been engaging in, calling tribal elders to meet with him, giving them gifts of ceremonial turbans or rugs. Akrem could not understand why the U.S. forces seemed to be helping Shirzai so assiduously. “The Americans do everything for Gul Agha and Khalid Pashtoon,” he remarked with wonderment. “The schools, the wells, all are for the Barakzais. But it's only a small tribe. Gul Agha doesn't even need this American money; he's got the customs revenues.” Kandahar customs officials were all Shirzai's Barakzais, and so far, not a penny of the estimated $5 to $8 million dollars a month that was being collected at the gates of Kandahar was making it to central government coffers in Kabul.