The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914 (14 page)

Read The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

In Winnipeg he felt powerless to cope with the Doukhobor influx. It was easy enough, he told Smart, to ship 2,073 people by train from the East, “but to take hold of 2073, house and feed them, look after the sanitary arrangements and prevent them from being frozen to death is not an easy task. Our weather here has been from twenty to forty below zero for two or three weeks with a bad blizzard blowing.…”

He had no authority to make purchases. No committee had been organized to handle Doukhobor funds and no line of credit issued. He needed to buy wood, water, harnesses, oxen, sleighs, flour, and vegetables. He could not find sixty-gallon cauldrons in the West; these would have to be shipped by freight, and that would take a week or ten days or even longer, should there be a blizzard. “It will then take twenty-four hours to set them up,” McCreary reminded Smart, “so I should know now more particulars of what my powers are.” In the end he did the only thing possible: he dipped into his own departmental funds and endured a tough reprimand from Ottawa for doing so.

The five trainloads of Doukhobors began arriving in Winnipeg at 12:30 on the afternoon of January 27, 1899. The first train, delayed by weather at White River, was destined for Yorkton. But the shed there was not yet complete, and with the temperature now at forty-five below, McCreary did not feel it safe to house anybody there until the stoves and cauldrons had been going for at least twenty-four hours. He crammed 296 into the Dufferin School in Winnipeg – “forty more than its capacity” – and kept the rest in the immigration hall.

This was the coldest winter in the memory of the city’s oldest inhabitants. The third train did not pull into the station until one o’clock in the morning; by then it was so cold on the platform that McCreary froze his nose and fingers. Train No. 4 was an hour behind, en route to Brandon and making slow time, being forced to stop periodically to make steam when the engines froze. The fifth train arrived at 5:30 a.m. and collided with a yard engine just as it pulled out for Dauphin. Two cars were damaged and had to be replaced.

But the Doukhobors were in a state of near ecstasy. To them, McCreary’s makeshift arrangements were little short of Elysian. Hot dinners awaited them the moment they stepped off the train: the women of Winnipeg had spent hours peeling potatoes, chopping cabbage, making soup. Thousands turned out the following day to greet them. An address of welcome was offered by R.G. Macbeth, a local minister heading a committee especially organized for that purpose. As Wasil Papsouf stood up to reply, his face wreathed in smiles, there were tears of emotion in the eyes of the onlookers.

“God has been good to us,” Papsouf said. “We have come to a country where oppression does not exist. The kindness of your people has deeply impressed us all, and we are thankful. Everything has been first class.” As the spectators applauded, all the Doukhobors dropped to their knees and bowed their heads to the ground. That night, one of the leaders, Leopold Soulerkitsky, wired to Count Tolstoy:

“Safe. Doukhobors obtained grand welcome from Canada. All are free

.” As far as the Spirit Wrestlers were concerned, their problems were over.

McCreary’s were just beginning. He had managed to house two-thousand-odd Doukhobors in temporary quarters. Now he was faced with four new concerns: clothing his charges, moving food out to the various accommodations, providing more permanent housing, and doing all this before the next two thousand arrived. These were already aboard the Beaver Line’s

Lake Superior

, due to reach Halifax in a fortnight’s time.

The Doukhobors were ill prepared for the forty-five below weather. The men wore hard leather boots with pieces of blanket around the feet in lieu of socks. The women wore only a half-slipper with a leather sole. None had mitts. Several froze their toes trying to work out of doors. McCreary bought two hundred pairs of moccasins, four hundred pairs of socks, and a mountain of warm clothing for the men he was dispatching to prepare the new colonies for the others.

The staple food was simplified. Cheese, molasses, and fish, which some had been fed at Brandon and Portage la Prairie, were cut off because the Doukhobors themselves insisted that they all get the same provisions. The regular diet would be potatoes, onions, cabbage, tea, and sugar. But it soon became impossible to move the vegetables by sleigh because of the weather. “To try to keep vegetables warm by putting a stove in a sleigh would be impossible as they will quite likely meet with some upsets.” Nor was there any place to store perishables. Early that fall, Aylmer Maude had spent two thousand dollars on

vegetables. All had rotted in Winnipeg. When McCreary finally received the government advance in February for the first group of Doukhobors it was two thousand dollars short of the promised ten thousand because of this unfortunate purchase.

Luckily for McCreary, the next contingent was held for twenty-eight days in quarantine because of an outbreak of smallpox aboard the

Lake Superior

. But the long delay was costly. The new arrivals still had to be fed, and the

CPR

had to be paid a stiff price for holding its trains at Saint John.

Meanwhile, McCreary had managed to outfit and supply gangs of ten men from each of the three colonies planning to settle in the West, who were cutting timber for houses. By February 9, one gang had erected three buildings in the settlement, each twenty-four-feet square and large enough to hold fifty or sixty Doukhobors. Food was still a problem. No teamster would go out, even for additional pay, in the face of the biting cold.

It was essential that the roundhouse at Selkirk be refurbished before the new trainloads arrived. McCreary had thirty Doukhobors working on the building, which had to be plastered and papered before it would be habitable.

And so it went, with McCreary shuffling thousands of people by train and ox team off to Yorkton to make way for the new arrivals, while gangs of men on the new village sites kept cauldrons of water bubbling to warm the plaster for the partially built homes. By February 9, the government payment of eight thousand dollars was gone and the Treasury Board was vacillating because of the quarantine delay. McCreary was told he would not receive the second payment of sixteen thousand dollars until June. A final payment of about eight thousand dollars was not made until the last contingent of Doukhobors reached Canada in the fall, many of whom were forced to live in caves for a portion of the winter. At that point the government was relieved of all payments based on the bonus of $4.87 for each immigrant settled in the West.

Much of the sum raised by the Quakers and Purleigh community had gone to pay transportation costs; the rest was not available until late in the summer. Thrown on their own resources, the Doukhobors rose to the challenge. Out went the men from Selkirk, Brandon, and Winnipeg, taking any job they could get from shovelling snow to chopping wood. The older men set up cottage industries, making wooden spoons and painted bowls for sale. The women responded to the local demand for fine embroidery and woven woollens. The

younger girls took jobs as domestics. Rather than purchase shovels and harnesses, the Doukhobor farmers bought iron bars and leather, built forges to produce implements, and fashioned Russian-style gear that was superior to the mass-produced Canadian harnesses.

Meanwhile, James Mavor had persuaded William Saunders of the Dominion Experimental Farm to visit the villages and give advice on crops. He had also talked the Massey-Harris Company into selling the newcomers equipment on credit. By the summer of 1901, the Doukhobors had 40 binders, 70 mowers, and 120 ploughing machines in operation. Thus, with the help of a number of dedicated and generous friends, these extraordinary people were well on the way to self-sufficiency.

In spite of all the problems, the Doukhobor resettlement was a remarkable feat. In a little more than a year after Prince Kropotkin wrote his original letter to Mavor, Canada had managed to settle seventy-five hundred persecuted and poverty-stricken Russians on the black soil of northern Saskatchewan. Within another year, their villages had been built and their future, it seemed, was secure. Yet the seeds of future trouble had already been sown – by the government in its eagerness to complete a vague and ambiguous contract and by a small but fanatical group of Doukhoborski to whom the true promised land was not in Saskatchewan at all but in the dreams and visions of their leaders.

3

The “peculiar people”

Who were these “peculiar people” now struggling to build their communal homes and villages in three colonies in Saskatchewan? They were not nearly as monolithic as the naïve Tchertkoff had believed and as McCreary came to realize: “They are not by any means Universal Brethren, from the fact that they do not altogether agree on every point; they have their dissensions like ordinary mortals, so that a little difficulty may arise at times of this nature. Some of them, too, I understand, at Portage la Prairie, especially, are calling for fish, so that they are not all strictly vegetarians.”

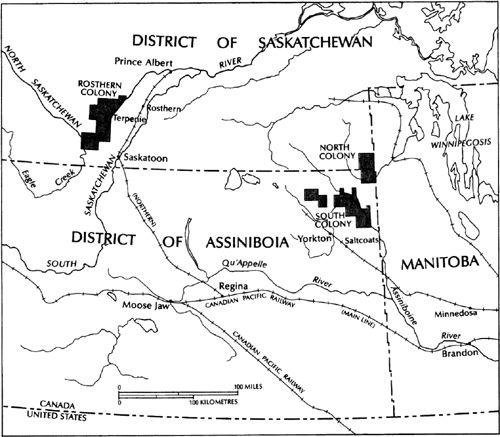

This was a prescient assessment. In 1886, the death of their passionate leader, Lukeria Vasilevna Gubanova, and the disputed choice of her selected heir, Peter Vasilivich Verigin (rightly or wrongly believed to be her young lover), had caused a split in the sect, which was further Doukhobor Settlements in Saskatchewan divided geographically by Russian persecution. Some Doukhobors were vegetarians; some were not. Some were comparatively wealthy; some were destitute. Some believed in independence, others in conformity. In Canada, the divisions continued. The Georgian group went to Thunder Hill, seventy miles north of Yorkton; it became known as the North Colony. The refugees from Cyprus went to Devil’s Hill, thirty miles north of Yorkton, the “South Colony.” The people from Kars went to the “Prince Albert” or “Rosthern Colony” between Saskatoon and Prince Albert.

Doukhobor settlements in Saskatchewan.

In general, the Doukhobors believed that Christ lived in every man and thus priests were unnecessary and the Bible obsolete. They rejected churches, litany, ikons, and festivals. Their only allegiance, they insisted, was to Christ; they could take no oath to temporal power. And yet their subservience to Peter Verigin seemed almost total.

Since 1886 Verigin had been in exile in Siberia, where he too had come under the influence of Tolstoy’s teachings. His directives, sent secretly to the community’s headmen, had been partly responsible for

bringing about the persecution of the Doukhobors under Czar Nicholas II. Verigin advocated a form of Christian communism, vegetarianism, abstinence from alcohol and, in times of tribulation, sex. He issued a ban on killing of any living thing, including human beings – hence the refusal to serve in the Czar’s army. But Verigin’s directives were often subtle and ambiguous, causing dissension within the sect.

When all of Verigin’s flock was settled in Canada, another directive arrived from Siberia. It was permissible, the leader said, to learn to read and write. All essential goods, all shops, smithies, storehouses, granaries and the like should be held in common. Villages should not contain more than fifty houses, each capable of sheltering an extended family. Trees should line the streets; windbreaks must be planted and orchards cultivated.

By the end of 1900, a total of fifty-seven villages had sprung up in the three communities, most containing fewer than twenty houses. James Mavor, who was sent out by Sifton in April 1899 to report on the Doukhobors, spent three weeks in one of these one-room buildings with Prince Hilkoff. The house was built of logs, caulked with clay, and heated by a single stove. On two sides of the big room were double tiers of bunks, fourteen in all, each seven feet long and five feet wide. In each bunk an entire family slept together. Mavor and Hilkoff had one to themselves. The remaining thirteen accommodated fifty persons.

In that first summer there was scarcely an able-bodied man left in any of the villages. While they worked on the railway, the women broke the sod. Since the few horses available were needed to bring supplies from Yorkton, the women hitched themselves to the ploughs – twenty-four women to each team, guided by one of the old men of the village. A photograph of one of these teams appeared in the Conservative newspapers, which reviled the Doukhobor men as inhuman beasts who forced their womenfolk into harness.

By 1900, the men themselves were back at work in the fields. Life was hard, yet there is an engaging quality to the descriptions of Doukhobor society – the choir chanting in the streets each morning to wake the workers; the men, divided into gangs, singing as they marched toward the fields; the town meeting or

sobranie

, where a rough democracy prevailed; the antelope and deer foraging unmolested among the cattle; the family dipping their wooden spoons into the communal bowl of borscht.

Those officials who came into contact with the Doukhobors were impressed. “I never saw a more orderly lot of people,” the Mounted Police inspector at Duck Lake wrote in August 1899. One immigrant

agent aboard a Doukhobor train wrote: “I take the greatest pleasure in stating that during my many years travelling with passengers of so many different nationalities, I never came across a more clean, respectable, well behaved lot of people.” The veteran Mounted Police Inspector Darcy Strickland was astonished to note that they never passed one another on the village streets without removing their caps and bowing. Old men bowed to children, and the children bowed back. It was explained to him that they were not really bowing to each other but to the spirit of Jesus within them.