The Prince Commands: Being Sundry Adventures of Michael Karl, Sometime Crown Prince & Pretender to the Thrown of Morvania

Authors: Andre Norton

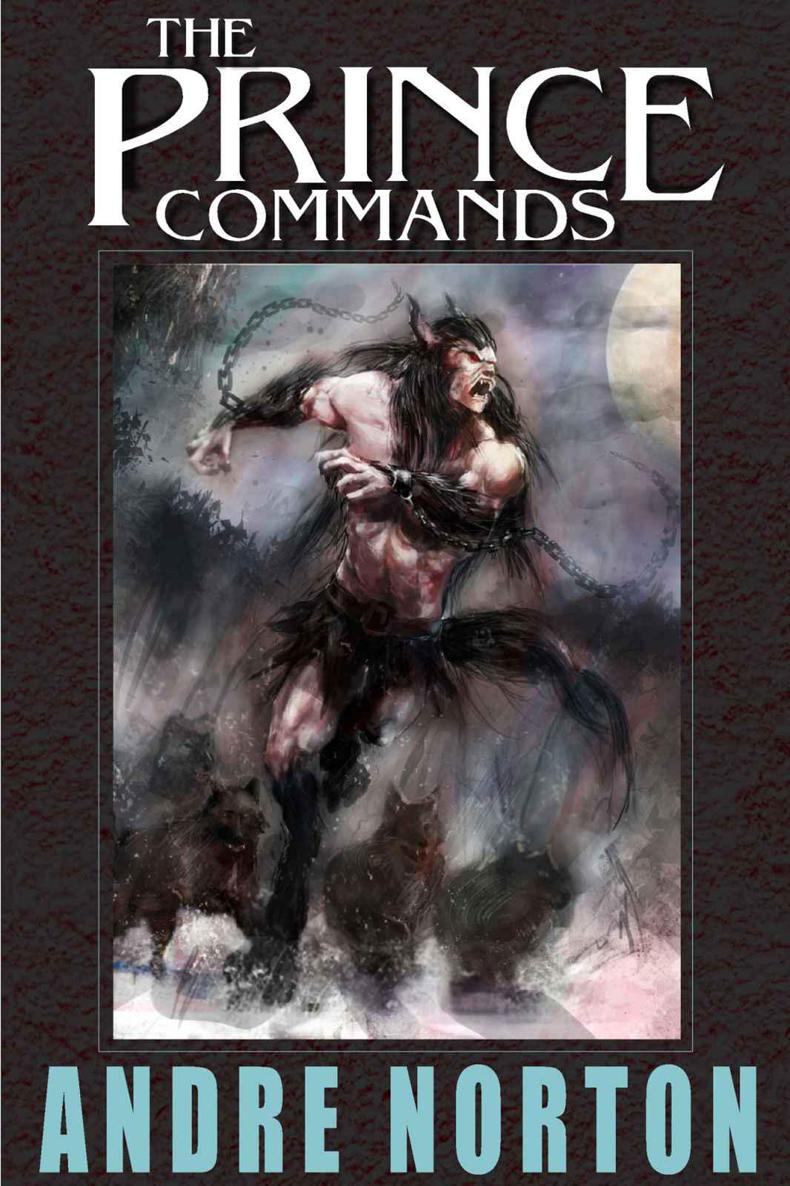

From close by in the forest came an eerie cry followed by a yapping chorus, and out of the trees at the edge of the gravel swept a little band of dark horses attended by a howling pack of what Michael Karl first thought were dogs. And then he saw more clearly—they were wolves!

The riders were an uncanny mixture of wolf and man, masked completely by shaggy gray wolf skins drawn over the upper parts of their bodies. They cantered silently down upon the train in dead quiet except for the excited yelps of their four-footed companions, whom they kept in order with long whips.

Black Stefan had come!

Also By Andre Norton

Garan The Eternal

Gryphon In Glory

High Sorcery

Horn Crown

Iron Butterflies

Lore Of The Witch World

Merlin’s Mirror

Moon Called

Moon Mirror

Octagon Magic

Red Hart Magic

Sargasso Of Space

Snow Shadow

Spell Of The Witch World

Stand To Horse

The Gate Of The Cat

The Jargoon Pard

The Sword Is Drawn

Trey Of Swords

Velvet Shadows

Wheel Of Stars

Yurth Burden

Zarsthor’s Bane

Wizard Worlds

ANDRÉ NORTON

THE PRINCE

COMMANDS

Premier Digital Publishing - Los Angeles

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

The Prince Commands

Copyright © 1962 by Andre Norton

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

ISBN: 0-523-48058-X

eISBN: 978-1-937957-55-1

Premier Digital Publishing

www.PremierDigitalPublishing.com

Follow us on Twitter

@PDigitalPub

Follow us on Facebook: Premier Digital Publishing

Author's Note

Once, some few years ago, a boy begged a story of me. It was to be of “sword fights and impossible things.” I complied as best I could with this imaginary tale of Courts and Castles, Crown Princes and Communists. The telling of it was not in days, or weeks, but in months. However, I fulfilled my promise.

Here,

John,

is your story of “impossible things.”

Chapter I

Michael Karl Learns What He Has Wanted To Know

“D'you know,” Michael Karl flicked the chin of the boy in the mirror lightly with the thong of his riding crop, “d'you know that you're an awful disappointment and rather a failure?”

He attempted a stern frown but only succeeded in wrinkling his smooth forehead and twisting his level black eyebrows almost together.

“Oh, I know, m'lad, you can stick on a horse and know which end of a saber one holds. And I'm not denying that you can shoot at least decently straight and can order a breakfast in French. Nor do I forget that you can't remember tons and tons of European history which you've learned. But—Michael Karl—you, an American, don't know a thing about America, the country you live in. And you're a bit of a coward into the bargain.”

The boy in the mirror dropped his gray-green eyes, and his thin lips became very straight indeed. Without looking at him again, Michael picked up his gloves and started for the door, his spurs rasping on the polished floor.

“Yes,” he repeated, “you're a coward; you're afraid of your guardian and he but a man like yourself. No, not like yourself,” Michael Karl sighed at his lack of inches and thought regretfully of the Colonel's six feet. The Colonel, that grim man, was the only family Michael Karl had had since his parents had been killed a month after his birth.

He straightened up to the last inch of his five-feet-six. It was his abiding misfortune that he was small, not short but small. He always had difficulty in getting gloves and boots to fit his long-fingered hands and high-arched feet and his clothes had to be made to order.

“Look at Napoleon,” he comforted himself aloud, “I can imagine that a lot of people wished

him

smaller than he was.”

But his lack of inches didn't produce his awe of the Colonel, at least he thought it didn't. As he was wondering whether it did, he opened the front door.

Outside, where a harum-scarum March wind was frolicking with the gardener's neat piles of last year's leaves and flower packings, he lost his soberness. He even attempted to whistle as he stood waiting for the groom to bring his mare around.

For yesterday Michael Karl had had an adventure and to-day he was calmly planning to have another, all without the knowledge of the Colonel. And adventures were something Michael Karl had read about rather than experienced for the past eighteen years.

The Duchess came dancing around the drive from the stables with Evans at her haughty head. She had a wicked eye that morning, had the Duchess, and she promised some fun.

“She do be that flighty, sir.” Evans was puffing a little. Her Grace had led him a merry dance.

“So I see.” Michael Karl mounted. He had always wondered how heroes of romance “vaulted into the saddle.” Some day when he had lots of time he would try it.

“Please, sir, will ye be a-lettin’ me go with ye?” The Colonel, he was that mad about yesterday.”

“Did you tell him?” demanded Michael Karl.

“No, sir. What would I be a-doin’ that fer? He saw ye.”

Michael Karl glanced nervously at the house, and, as he had expected ever since Evans had spoken, the stiff, ramrod figure of the Colonel stepped out on the terrace.

“You will please dismount and come in at once,” said the Colonel dryly.

Feeling like a badly whipped small boy Michael Karl obeyed. The Colonel

would

wait until he was almost out of reach before he'd spring. As he had a hundred times before, Michael Karl rebelled silently against the Colonel's favorite cat and mouse game.

“I'll be a-tellin’ the boy on the hill that ye're not comin'?” Evans whispered.

Michael Karl nodded and thanked him with a smile. He went in slowly to find the Colonel waiting in the hall.

“The library, please,” said that gentleman crisply.

Once there the Colonel seated himself in the

desk chair while Michael Karl took his place before the desk. He had stood there so often he was surprised that the rug didn't show the wear. The Colonel let him stand awhile in silence before he began; that too was the usual procedure.

“You intend to become a soldier?”

“Yes,” answered Michael Karl dutifully. He knew all the questions and answers by heart now.

“How do you expect to command men when you can't obey orders yourself?”

There was no answer for this one.

“Haven't you had distinct orders that you are not to speak to any one outside the gates unless it is absolutely necessary?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then why did you deliberately meet that young man on the hill yesterday and hold a long conversation with him?”

“Because,” answered Michael Karl defiantly, “I wanted to.”

The Colonel's sharp face showed no change though it was an unheard-of thing for Michael Karl to answer back.

“You keep me in here like some sort of a prisoner—I can't do this and I can't do that. And if I ride out I must take a groom to see that I don't speak with any one. Why?

“That fellow I spoke to yesterday was a scoutmaster out with his troop. I was interested and stopped to ask some questions. Was that a crime? Tell me, why do I have to live like this? Yesterday morning I didn't think this life was very strange; you always told me that wealthy boys had to live like this. But I learned some things from that scoutmaster and now I know that all wealthy boys aren't prisoners like I am. And why don't you ever mention my parents or answer my questions about them? Who and what am I?” Michael Karl flung his questions at the stiff man behind the desk.

“Attention!” snapped the Colonel, but for the first time in his life Michael Karl refused to obey.

“I'm through,” he said flatly. “Unless you can give me some good reason why I should, I am through obeying orders. And now I'm going to take that ride you interrupted. And I'm going to the scout camp and stay as long as it pleases me.” Michael Karl felt his power of rebellion growing with every word.

“You are going to your quarters under close arrest,” said the Colonel quietly.

Close arrest meant his bedroom and bread and water for a week, but the threat failed to bring him to terms as it had in the past. Michael Karl was through with being a “bit of a coward.”

“And if I refuse?”

The Colonel lifted his eyebrows. “I hardly think that at your age you would desire being carried upstairs by the servants.”

Michael Karl flushed painfully. The Colonel was capable of ordering that very humiliating thing.

“You win,” conceded Michael Karl. “But—”

“Yes?”

“Oh, what does it matter?” Michael Karl was beaten again. He dragged up the stairs and into his room, hating himself.

It was a cheerless place, his room; the Colonel didn't believe in too much comfort. A cot bed, two straight-backed chairs, shelf of heavy, dull-looking books, a table and a lamp couldn't make the room look overcrowded. Michael Karl threw his gloves and crop on the table and went to stare out of the window before he thought of something and smiled.

The Colonel hadn't won on all points after all. Michael Karl pulled two of the solid books and felt behind them. Yes, it was still there.

He took out a blue book with limp covers. On one of his carefully supervised trips to town he had caught a glimpse of it in a window, and Evans had been sent to purchase it the next day. Before its purchase Kipling had been just a name in a literature book, and the Colonel went very light on literature as a part of Michael Karl's education. But now Kipling was a very real person who wrote gorgeous verse about soldiers.

Michael Karl curled up on the cot in a way that he knew the Colonel would hate and opened the book to the “Road to Mandalay,” which he was learning. Let the Colonel think he was reading “Field Fortifications” or some such rot.

It wasn't the first time he had spent his hours in disgrace reading forbidden literature. Evans smuggled him the magazines, newspapers and books upon which the Colonel thought it unnecessary for him to waste his time. What Michael Karl knew about the America outside his gates, and it was a surprising lot, he had learned through reading.

The light had begun to fade when some one knocked on the door. Michael Karl crossed the room with guilty haste and slid the book back in its old hiding place.

“Who's there?” he asked.

“The Colonel wants to see you in the library, sir.”

Michael Karl was startled. It wasn't like the Colonel to jaw him twice the same day. Unless, Michael Karl frowned, unless he had found that pile of magazines in the summer house.

With a guilty conscience as regards the magazines, he pulled his tie straight and smoothed down his hair. The Colonel worshiped neatness, and if Michael Karl went in to him with ruffled hair—The Colonel also insisted upon promptness, and Michael Karl clattered down the stairs at top speed.

Outside the library door he hesitated. The Colonel wasn't alone. Some one with a deep and growly voice was doing all the talking. Michael Karl had the queerest feeling of fear, as if he should not knock on that door but run as far from it as possible. He knew that there was something behind it which threatened him.

Michael Karl knocked.

“Come in,” ordered the Colonel, and Michael Karl obeyed.

To his surprise the room seemed crowded with people and it took him a second or two to get them sorted out. What was even more disconcerting, he seemed to have released a spring when he opened the door, for they all clicked their heels and bent stiffly at the hips in his general direction.

“This is His Royal Highness,” the Colonel was saying. Michael Karl felt as he once had when he missed a step at the head of the stairs and bumped down jerkily step by step.

Was

he a Royal Highness? If so, why?

He appeared to be one all right. They, the fat red-faced man with the too-tight collar, the mummy in black, and the very pale young man, were all looking respectfully right at him, Michael Karl.

“A chair for His Royal Highness,” commanded the fat man in the deep voice Michael Karl had heard through the door.

The pale young man dragged one out, and Michael Karl seated himself rather gingerly. This Highness business was decidedly upsetting. However, the Colonel looked as if he had eaten something sour, and that brightened things up a bit.

“His Royal Highness,” said the Colonel in a thin, dry voice, “has been kept in ignorance of his rank in accordance with His late Majesty's wishes.”

Michael Karl wished that they would quit talking about him in the third person, it made him feel as if he weren't there at all.

“Quite right, quite right,” boomed the fat man. “You may inform His Royal Highness now.”

The Colonel turned towards Michael Karl and began reciting in the monotonous tones of a lecturer. “Your Royal Highness's father was the second son of His Majesty, King Karl of Morvania. While an exile in America, he contracted a marriage which was highly displeasing to His Majesty. Prince Eric was killed with his bride in an accident soon after Your Royal Highness's birth. His Majesty gave orders that you should be educated as one of your rank but that you were not to enter Morvania unless you were sent for.”

Michael Karl had been told all his life that a gentleman never shows emotion, but he couldn't control the little gasp of surprise. He, Michael Karl, was a prince, the grandson of a king. Now he knew it was a dream, one of those queer nightmares where everything is topsy-turvy.

“A year ago,” the Colonel continued, “His Majesty was assassinated while visiting his city of Innesberg. And then the Council of Nobles assembled and took control of the government for one year in accordance with the law. Unfortunately the Crown Prince was killed in a mountain accident, and, the year of regency being ended, the throne passes to Your Royal Highness.”

He stopped and they all stared at Michael Karl. Evidently he was expected to make some sort of an answer. What if he told them the truth? Michael Karl had no desire for royal honors. He had had more than a taste of a prince's life, if, as according to the Colonel, he had been living the life of one of his rank. All he wanted was his freedom.

He drew a deep breath.

“Nothing doing,” said Michael Karl distinctly.

They all leaned forward as if they hadn't heard.

“May—may I ask what Your Royal Highness means by that extraordinary statement?” questioned the fat man at last.

“Just what I said. I'm through. You can go hunt up another king for your country. I'm an American citizen (he was basing his statement on something he had once read and hazily remembered) and I'm staying right here.”

The Colonel broke the shocked silence. “With persons of Your Royal Highness's rank there is no question of citizenship. Your Royal Highness is sailing to-morrow.”

His Royal Highness so far forgot himself as to murmur “Really?” at this observation.

“And just how are you going to get me out of the country if I don't want to go?”

“There are ways,” answered the Colonel.

Michael Karl shivered. He knew something of the Colonel's “ways.” Perhaps it would be better if he were to give in now and do his fighting later when they had forgotten to watch him. He had no idea where Morvania was, but it sounded like something in the Balkans and that was pretty far away. If he couldn't get away before they reached there, why, he'd deserve to be a prince.

“Perhaps,” suggested the fat man suavely, “you had better present us to His Royal Highness.”

The Colonel came to life again. “General Oberdamnn,” the fat man clicked and bowed. Michael Karl immediately gained a very poor idea of the army which called him General. “Count Kafner,” the mummy in black permitted itself a creaking bow. “And Baron von Urdlemann, Your Royal Highness's aide-de-camp,” the pale young man bent forward. Michael Karl wondered if all Morvanians had that distressing shade of taffy-colored hair.

Michael Karl arose. He was puzzled about the editorial “we.” Did princes use it or not? He decided against it.

“I thank you, gentlemen, for your attendance, and I trust we shall have a very pleasant journey.” He seemed to have said the right thing; anyway, no one looked disturbed.