The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (44 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

“I believe Jimmy Carter to be a decent man, and his impulse is entirely sincere. He is a truly religious Southern Baptist. I’m told that he prays privately several times a day and that each night, before retiring, he and his wife study the Bible together in Spanish, to lend scope to their learning. As a genuine born-again Christian he lives by the conviction that God has placed him on this earth to fulfill a destiny. He sees himself as a healer, and as a healer he wants to bring peace to the Holy Land. Yet much as I respect his religious convictions, I doubt, as did Rabin, his grasp of the complexities of the Middle East. Certainly, he shows little comprehension of the Jewish right to Eretz Yisrael, nor of our genuine security concerns. But since I believe him to be an honest man I have to believe he can detect the truth when he sees it, and is, therefore, open to persuasion.”

With that he turned to General Poran, and said, “Freuka, please prepare for me three maps

–

the first showing

PLO

concentrations in southern Lebanon, the second showing Israel’s minute size compared to our twenty-two Arab neighbors, and the third, the tiny distance between the old nineteen sixty-seven border and the Mediterranean Sea. And since Americans love to put initials to everything”

–

this with that cheeky look

–

“let’s call that third map the

INSM

.”

“Which stands for?” asked Freuka.

“Israel’s National Security Map, of course,” he replied. Then, to Kadishai, “Yechiel, prepare a list of American towns with biblical names, state by state. And finally, to me, “Please try and make yourself available this coming Shabbat afternoon? We’re hosting an open house. You’ll help us entertain.”

The Open House

The weather in Jerusalem was warm and breezy that Shabbat afternoon, adding spice to the smell of poplar and pine that always fills the air of Rehavia in high summer. In this upscale neighborhood stands the spacious official residence of the prime minister, and on this particular Shabbat, under a blue sky streaked with tangerine wisps of cirrus that heralded the onset of sunset, tourists, soldiers, yeshiva boys, neighbors, and even casual passersby lined up at the gate waiting their turn to enter.

For as long as anyone could remember, the Begins had hosted a Shabbat afternoon open house in their modest Tel Aviv home. They were intent on continuing this practice in their official Jerusalem residence. The contrast between the two dwellings was staggering. In Tel Aviv they welcomed their guests into a cramped, two-room, ground-floor apartment at Number 1 Rosenbaum Street, where they had raised their son and two daughters. Friends, acquaintances

–

anyone

–

would drop by to say

“

Shabbat shalom

,” shmooze over a glass of orange juice, and with the coming of the night, wish one another a

shavua tov

–

a good week

–

and be on their way.

When Menachem Begin unexpectedly became leader of the country and word spread that he intended to continue the open house tradition, the anticipation of it became a source of matchless pleasure to the general public and an unmatched migraine to the security service. No prime minister had ever flung open his door to all and sundry before, and the people in charge of his security were at a loss as to how to handle it.

“

Shabbat shalom

. Come in. Have a cold drink,” cried Mr. and Mrs. Begin welcomingly, extending a hand to all visitors as they walked through the door. Many were holding housewarming gifts of cake, flowers, chocolate, and wine. Some were so awestruck they instinctively bowed and tiptoed across the threshold.

Once inside, visitors hung about gawking at the expansive living room, with its blend of old-style European and contemporary Israeli furnishings set out on rich carpets. They silently admired the crystal chandelier in the dining room, the paintings on the walls by famous Israeli artists, the solid silver Shabbat candelabras still coated with wax, and the framed pictures of the grandchildren on the grand piano. And while they stood and stared, the two Begin daughters, Hassya and Leah, and an older grandchild, circulated among them, carrying trays of juice and soda and cookies, and urging everybody to feel at home.

One skinny old man dressed in his Shabbat best, with pockets of fatigue under his eyes, and jaws and jowls drooping with mourning, peered into Mr. Begin’s face as though studying an object at a museum. He refused to let the prime minister go until he had examined a snapshot of his wife and four children, discolored and crumbling. He thrust it under Begin’s nose, gesticulating and shouting in Yiddish, that in all his years at Auschwitz, where his family was gassed, he had never let go of this photograph, and that whenever the SS searched him he stuffed it into his mouth, which was why it was so cracked and creased and smeared.

Begin clasped the man to his breast and the survivor’s voice gradually trailed away, and his eyes went misty. A silent thread of communication passed between them, calming the man immensely. He blinked back his tears and wordlessly walked away.

Next, a Yemenite with a wispy beard, tight side-curls and a white skullcap with a tassel on top stepped forward, and introduced himself as a grocer. Asked where his place of business was, he named a run-down neighborhood, prompting the prime minister to announce, “I want you to tell your customers and all your friends, in my name, that we are going to renew your neighborhood.”

“Renew? What does that mean?” The grocer was totally perplexed.

“It means our new government is elaborating a plan called Project Renewal. With the help of our Diaspora brethren

–

the United Jewish Appeal and Keren Hayesod

–

we shall eliminate all the slums of Israel, including yours. We shall restore your homes and build new ones in consultation with you, the inhabitants. It will be a cooperative effort and,

b’ezrat Hashem

[God willing], we shall make all our neighborhoods places where people will be proud to live.”

The grocer listened intently, trust softening his sun-blasted face, and then he abruptly bent his knee to deferentially kiss the prime minister’s hand. But Mr. Begin would have none of it. “A Jew bends his knee to no one but to God,” he reprimanded gently.

By now the place was packed, so I stepped into the garden that led off from the living room to get some air. Here, too, people were gathered, among them a driver I recognized from the prime minister’s office. His name was Rahamim, and he was in the company of a dozen or so muscular young men, all wearing

T

-shirts and expertly cracking roasted sunflower seeds between their teeth. Insisting I join them in their feast, they regaled me with tales of Menachem Begin’s love fest with Sephardic Jews like themselves.

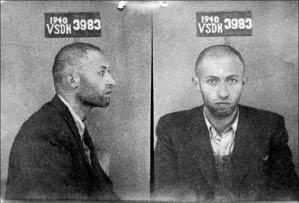

It was the twilight hour, and the prime minister himself stepped out of the crowded living room into the floodlit garden, his animated features lit by a dazzling smile. His entry was welcomed with whistles and applause. Among the eager faces which greeted him was one belonging to a frail figure in a baggy suit, with the pale skin of an underfed convict and teeth the color of khaki. Most of his hair was gone except for a crescent of iron-gray bristles. He looked at least fifty, and he bowed with a stiff, brittle dignity as he clasped Mr. Begin’s hand.

Speaking in a fluent Hebrew, he said his name was Misha Lippu, an artist by profession, and that he had just been released from a Romanian penal colony after five years of imprisonment. He had arrived in Israel two days before, under the quota system which the Israeli government negotiated annually at a high price with the Romanian communist dictator, Nicolae Ceauşescu, enabling a trickle of Jews to emigrate.

All guests within earshot stood in rigid attentiveness as Begin gripped the man by the shoulders and in a tone of fervent compassion and respect, said,

“

Shalom Aleichem! Baruch haba!

”[Welcome! Welcome!]

Lippu lowered his gaze and compressed his lips which began to tremble in emotion, causing Begin to grip him harder, saying softly, “It’s all right Mr. Lippu. You’re among your own now. You’re home. You’re safe. No one can harm you.” And then, brightening up, “From whence your Hebrew? It’s so fluent.”

Energized by the question, Lippu wiped his eyes and explained that in his younger years he had studied at a yeshiva, and that in the penal colony there had been a Catholic priest, a Father Oradea, who knew classical Hebrew well. So they spoke it and did exercises together. “Father Oradea was imprisoned as an

agent provocateu

r

,” said Lippu, matter of factly.

“And you

–

what was your crime?” probed Begin.

“I was charged with being a Zionist conspirator.”

Begin closed his eyes for a moment, and mumbled knowingly, “I am very familiar with the term. And what, specifically, were you found guilty of?”

A parade of intense emotions raced across Misha Lippu’s face, and he chewed on his knuckles to get a grip on himself. “Jewish and Zionist art,” he answered flatly.

Begin was nonplussed.

Compulsively, Lippu told Begin that after he’d left the yeshiva world he’d followed his artistic calling and enrolled in an art academy. When the Stalinists came to power they enforced a proletarian style of art for which he received many commissions over many years. He became well known, and was showered with honors. This won him disdain from connoisseurs and adulation from those he disdained

–

the fat cats and the apparatchiks. So, in the end he gave that up and began painting Jewish devotional and Zionist themes that expressed his innermost emotions. He was warned many times to stop, but he didn’t. Under the Stalinist penal code this amounted to conspiracy against the state. And that’s what landed him in the penal colony, where he was sent into the quarries to smash rocks.

The prime minister stared back at him with watery eyes, and said, “I, too, spent time in a gulag smashing rocks.”

Dumbfounded, Misha Lippu gazed hard at Begin, and whispered, “You were a prisoner of the communists, too?”

Begin nodded, and related how, on one fine day in September 1940, three Russian security agents came knocking on his door in Vilna, and took him away. At the time he was head of Betar in Poland and, a Soviet court declared him guilty of ‘deviationism,’ and sentenced him to eight years hard labor in a Siberian gulag. His Soviet interrogator told him, “You will never see a Jewish State,” and most fellow prisoners were equally disheartening, one telling him that the supposed date of his release

–

20 September 1948

–

was a fiction. Nobody ever left the camps alive. But then fate intervened. In the spring of 1941, Germany attacked Russia and the Soviets concluded an agreement with the Polish Government-in-Exile that led to his release. He joined the Free Polish Forces and reached Palestine with one of its units in 1942.

“Time for

Maari

v

” [the evening service], somebody called out. People gazed heavenward to check that three stars were visible in the sky, this being the sign that the Sabbath day was over. A group of men assembled in a corner of the garden to pray, and while they were doing so Mrs. Begin brought in from the kitchen a thick plaited candle, a silver spice box, and an overflowing goblet of wine. The brief service done, Mr. Begin lifted a granddaughter onto a chair, lit the candle, placed it in the child’s hand, and as she held it aloft, raised the wine goblet and recited havdalah, the closing ceremony of the Sabbath day. Then the whole throng chanted in full-throated chorus, “shavua tov” – the words that expressed the hope for a good week to come.

As the guests were leaving, the prime minister called out after them, again and again, “We leave for Washington shortly. Please come back and visit us after we return.” And the guests, bursting with delight, called back, “We will. We will.”

“No, they won’t,” muttered the exhausted and agitated chief security officer to his subordinates. “Such a free-for-all will not happen again.To the prime minister he said, “Sir, if you want to maintain your open-house tradition, all visitors will have to register beforehand, and each will be thoroughly vetted.”

“Pity,” sighed Begin. “It’s been such a beautiful way to keep in touch with the

amcha

” [the ordinary folk].

Photograph credit: Courtesy of Menachem Begin Heritage Center

Mugshot of Menachem Begin, 1940, as a prisoner in a Soviet labor camp