The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (25 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

“Oh, I shall, I shall,” gushed Fallaci with a huge hug, and I drove her back to the American Colony Hotel where the concierge informed her that her flight to Rome, scheduled for the following day, had been duly confirmed. We parted, and I assumed that was the last I would see of her.

I was wrong. The following night, at an outrageous hour

–

two in the morning according to my bedside clock

–

I was jerked out of bed by the peal of the telephone and, fumbling for the receiver, yawned into it, “Who is this?”

“Oriana Fallaci. I’m in Rome.” She sounded distraught.

“I know you’re in Rome. What do you want?”

Sobbingly she said, “I’ve been robbed.”

“Robbed

–

of what?”

“The tapes of my Golda interview. All my Golda Meir tapes have been stolen.”

I sat up. “How? When? Who?”

She churned out the answer in an intense machine-gun ratter: “I checked into the hotel. I took the tapes out of my purse. I put them in an envelope on the desk. I left the room. I locked the door. I gave the key to the desk clerk. I was away for no more than fifteen minutes. When I got back the key was gone. The door of my room was open. None of my valuables were taken, just the tapes. The police are here now. They suspect it’s a political theft, as if I don’t know that already.”

“But by whom?”

“An Arab looking for information, maybe; some personal enemy of Golda, maybe; even some journalist jealous of me, maybe. One thing for sure: I was followed. Somebody knew I was arriving in Rome today. Somebody knew the hour of my arrival. And somebody knew the hotel I’m staying at.”

“So what do you want of me?”

There was a pause, and I could hear her catching her breath. “I want you to arrange a repeat interview with Mrs. Meir.”

“That’s asking a hell of a lot.” I was wide awake now.

“Please try, please.” She was sobbing again.

“Okay, I’ll try. But I can’t promise anything. Send me a telegram explaining what happened and I’ll show it to Golda. It might help.”

Next morning the telegram came. It read:

MRS. MEIR EVERYTHING STOLEN STOP REPEAT EVERYTHING STOLEN STOP TRY SEEING ME AGAIN PLEASE

When I explained the circumstances, Golda’s face turned grim. “The poor, poor thing,” she said in motherly pity. But then her eyes went steely and her voice obstinate: “Obviously, someone doesn’t want this interview to be published, so we’ll just have to do it again. Tell her, yes, and find me a couple of hours soon.”

It was with much joy that the two women embraced one another once again when, a couple of weeks later, the interview was repeated

–

even better than before. Again, Golda Meir gave Oriana Fallaci all the time she needed.

Recalling the episode, Fallaci was to write:

Naturally, the police never got to the core of the mystery surrounding the theft of the tapes. But a clue did offer itself. At about the same time as my interview with Golda Meir, I had asked for one with Muammar el-Kaddafi [president of Libya]. And he, through a high official of the Libyan Ministry of Information, had let me know he would grant it. But all of a sudden, a few days after the theft of the tapes, he granted an interview to a rival Italian weekly. By some coincidence, Kaddafi regaled the correspondent with sentences that sounded like answers Mrs. Meir had told me…How was it possible for Mr. Kaddafi to answer something that had never been published and that no one, other than myself, knew? Had Mr. Kaddafi listened to my tapes? Had he actually received them from someone who had stolen them from me?

23

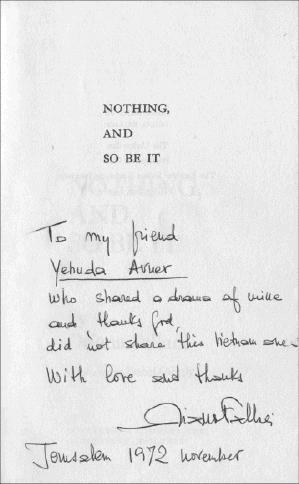

Shortly thereafter, Oriana Fallaci sent me a copy of her Vietnam War book,

Nothing, and So Be It

, with a dedication that read:

To my friend Yehuda Avner who shared a drama of mine and, thank God, did not share this Vietnam one. With love and thanks

–

Oriana Fallaci.

This bold chronicler of people and of wars was the only journalist I knew who had talked four times and for over six hours with Prime Minister Golda Meir. Well do I recall her last question at her last session which she put in a seemingly off-the-cuff manner:

“Mrs. Meir, do you really intend to retire soon?”

Golda’s response was a resolute earful:

“Oriana, I give you my word. In May next year, nineteen seventy-three, I’ll be seventy-five. I’m old. I’m exhausted. Old age is like a plane flying through a storm. Once you’re aboard there’s nothing you can do. You can’t stop the plane, you can’t stop the storm, you can’t stop time, so one might as well accept it calmly, wisely. So no, I can’t go on with this madness forever. If you only knew how many times I say to myself: To hell with everything, to hell with everybody. I’ve done my share, now let the others do theirs. Enough! Enough! Enough!”

She said this jabbing the air as if pointing to those who should be making her life easier. But then, she leaned back, and with one corner of her mouth pulled in a slight smile, she chuckled: “What people don’t know about me, Oriana, is that I’m really bone lazy by nature. I’m not one of those who

has

to keep busy all day. In fact, I like nothing better than to sit in an armchair doing nothing. Mind you, I do enjoy cleaning the house, ironing, cooking, and things like that. In fact, I’m an excellent cook. And, oh, something else

–

I like to sleep. Oh, how I love to sleep! And I also like being with people. To hell with serious political talk

–

I just like to chat about trivial, everyday things. And I love going to the theater and to the movies

–

but without bodyguards underfoot. Whenever I want to see a film they send out the army reserves. You call this a life? There are days when I would just love to pack it all in and walk away without telling a soul. If I’ve stayed so long in the job it’s only out of a sense of duty, nothing else. Yes, yes, I know, people don’t believe me. Well, they’d better believe me now! I’ll even give you the date when I’ll step down: October 1973. In October ’73 there’ll be elections. Once they’re over, I’m gone. It’s goodbye!”

Skeptics across the political spectrum tended to take her protestations with a grain of salt. After all, Golda Meir could never resist a challenge, and she was becoming increasingly embroiled in one right now

–

a fight against the spreading scourge of Arab terrorism. And when confronted with that kind of warfare she was no Venus; she was Mars.

Title page of celebrated journalist Oriana Fallaci’s book on the Vietnam War, with dedication to the author.

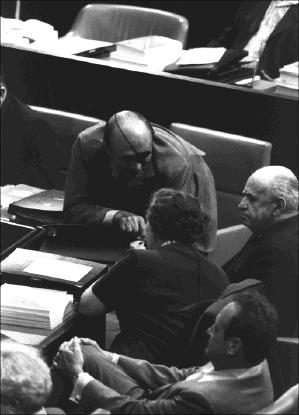

Photograph credit: Chanania Herman & Israel Government Press Office

Prime Minister Golda Meir consulting with her defense minister Moshe Dayan, 10 April 1973

The Shame of Schoenau

How does one treat with terrorists? Deal with them and you’re done for; don’t, and innocents die.

During 1972 and 1973, Arab terrorism against Israeli and Jewish targets was spreading like an epidemic across the whole of Western Europe: a Belgian plane hijacked en route to Israel; a Lebanese woman carrying weapons apprehended at Rome airport; eleven Israeli athletes mowed down at the Munich Olympics; a courier carrying weapons arrested at Amsterdam airport as he was about to board a plane for Israel; a Palestinian arrested at London airport charged with planning attacks on Israeli embassies in Scandinavia; an attack planned on the Israeli Embassy in Paris; an attempted attack on El Al passengers at Rome airport; an attempted attack on the Israeli Embassy and on an Israeli aircraft at Nicosia; an attack on the El Al office in Rome; letter bombs to Jewish and Israeli addresses in Britain and Holland; an attack on the El Al office in Athens.

And then came the shame of Schoenau

–

a tale of infamy that seized the assemblage of the Council of Europe in September 1973.

The Council of Europe in Strasbourg is that continent’s approximation of a representative House. At the time in question its approximately four hundred delegates watched with varying degrees of curiosity as Prime Minister Golda Meir, stooped and stern, mounted the podium. She was there at the invitation of the Council of Europe to state the case for Israel.

Generally speaking, Golda preferred to speak extemporaneously, but since this was a formal occasion protocol required she deliver a preprepared address. I, her in-house speechwriter, drafted one. It thanked the Council and individual European parliaments for raising their voices in support of Soviet Jewry’s right to freely emigrate to Israel [this was at the height of the worldwide “Let My People Go” campaign], delved into the intricacies of the Middle East conflict, pleaded for “the Council of Europe’s help to enable the Middle East to emulate the model of peaceful coexistence that the Council itself has established,” and concluded with a quote from the great European statesman, Jean Monnet, that “Peace depends not only on treaties and promises. It depends essentially upon the creation of conditions which, if they do not change the nature of men, at least guide their behavior towards each other in a peaceful direction.”

To my consternation, Golda never enunciated a single one of these words. Instead, she scanned the assembly from end to end, jaw jutting, brandished the written speech, and in a caustic voice, said, “I have here my prepared address, a copy of which I believe you have before you. But I have decided at the last minute not to place between you and me the paper on which my speech is written. Instead, you will forgive me if I break with protocol and speak in an impromptu fashion. I say this in light of what has occurred in Austria during the last few days.”

Clearly, the woman had decided it was idiotic to read her formal address after the devastating news which had reached her just before leaving Israel for Strasbourg.

A train carrying Jews from communist Russia to Israel via Vienna had been hijacked on 29 September by two Arab terrorists at a railway crossing on the Austrian frontier. Seven Jews were taken hostage, among them a seventy-three-year-old man, an ailing woman, and a three-year-old child. The terrorists issued an ultimatum that unless the Austrian government instantly closed down Schoenau, the Jewish Agency’s transit facility near Vienna where émigrés were processed before being flown on to Israel, not only would the hostages be killed, but Austria itself would become the target of violent retaliation.

The Austrian cabinet hastily met and, led by Chancellor Bruno Kreisky, capitulated. Kreisky announced that Schoenau would be closed, and the terrorists were hustled to the airport for safe passage to Libya.

The entire Arab world could hardly contain its glee, and a fuming Golda Meir instructed her aides to arrange a flight to Vienna after her meeting in Strasbourg, where she intended to confront Chancellor Kreisky, a fellow socialist and fellow Jew.

To the Council of Europe she said, “Since the Arab terrorists have failed in their ghastly efforts to wreak havoc in Israel, they have increasingly taken their atrocities against Israeli and Jewish targets into Europe, aided and abetted by Arab governments.”

This remark caused a fidgety buzz to drone around the chamber, and it seemed to deepen when she spoke in particular, and with great bitterness, about the eleven Israeli athletes kidnapped and murdered at the Munich Olympics the previous summer, an outrage compounded by the German Government’s subsequent release of the captured killers in return for the freeing of a hijacked Lufthansa plane and its passengers.

“Oh yes, I fully understand your feelings,” said Golda cynically, arms folded as tight as a drawbridge. “I fully understand the feelings of a European prime minister saying, ‘For God’s sake, leave us out of this! Fight your own wars on your own turf. What do your enmities have to do with us? Leave us be!’ And I can even understand”

–

this in a voice that was grimmer than ever

–

“why some governments might even decide that the only way to rid themselves of this insidious threat is to declare their countries out of bounds, if not to Jews generally then certainly to Israeli Jews, or Jews en route to Israel. It seems to me this is the moral choice which every European government has to make these days.”

And then, in a voice hardened ruthlessly, she thundered, “European governments have no alternative but to decide what they are going to do. To each one that upholds the rule of law I suggest there is but only one answer

–

no deals with terrorists; no truck with terrorism. Any government which strikes a deal with these killers does so at its own peril. What happened in Vienna is that a democratic government, a European government, came to an agreement with terrorists. In so doing it has brought shame upon itself. In so doing it has breached a basic principle of the rule of law, the basic principle of the freedom of the movement of peoples

–

or should I just say the basic freedom of the movement of Jews fleeing Russia? Oh, what a victory for terrorism this is!”

The ensuing applause told Golda that she had gotten her message across to a goodly portion of the Council of Europe, so off she flew to Vienna.

She was ushered into the presence of the Austrian chancellor, an affluently dressed, bespectacled, heavy-set man in his mid-sixties whom she knew to be the son of a Jewish clothing manufacturer from Vienna. She extended her hand, which he shook while rising with the merest sketch of a bow, not emerging from behind the solid protection of his desk. “Please take a seat, Prime Minister Meir,” he said formally.

“Thank you, Chancellor Kreisky,” said Golda, settling into the chair opposite him, placing her copious black leather handbag on the floor. “I presume you know why I am here.”

“I believe I do,” answered Kreisky, whose body language bore all the signs of one who was not relishing this appointment.

“You and I have known each other for a long time,” said Golda softly.

“We have,” said the Chancellor.

“And I know that, as a Jew, you have never displayed any interest in the Jewish State. Is that not correct?”

“That is correct. I have never made any secret of my belief that Zionism is not the solution to whatever problems the Jewish people might face.”

“Which is all the more reason why we are grateful to your government for all that it has done to enable thousands of Jews to transit through Austria from the Soviet Union to Israel,” said Golda diplomatically.

“But the Schoenau transit camp has been a problem to us for some time,” said Kreisky stonily.

“What sort of a problem?”

“For a start, it has always been an obvious terrorist target

–

”

Golda cut him off, and with a strong suggestion of reproach, said, “Herr Kreisky, if you close down Schoenau it will never end. Wherever Jews gather in Europe for transit to Israel they will be held to ransom by the terrorists.”

“But why should Austria have to carry this burden alone?” countered Kreisky with bite. “Why not others?”

“Such as whom?”

“Such as the Dutch. Fly the immigrants to Holland. After all, the Dutch represent you in Russia.”

It was true. Ever since the Russians had broken off diplomatic relations with Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War the Dutch Embassy in Moscow had represented Israel’s interests there.

“Oh, I’m sure the Dutch would be prepared to share the burden if they could,” responded Golda, trying to sound even-tempered. “But they can’t. It doesn’t depend on them. It depends entirely on the Russians. And the Russians have made it clear that they will not allow the Jews to fly out of Moscow. If they could we would fly them directly to Israel. The only way they can leave is by train, and the only country they will allow Jews to transit through is yours.”

“So let them be picked up by your own people immediately upon arrival in Vienna, and flown straight to Israel,” argued the Chancellor, holding his own.

“That’s not practicable. You know and I know that it takes guts for a Jew to even apply for an exit permit to leave Russia to come to us. They lose their jobs, they lose their citizenship, and they are kept waiting for years. And once a permit is granted most are given hardly more than a week’s notice to pack up, say their goodbyes, and leave. They come out to freedom in dribs and drabs, and we never know how many there are on any given train arriving in Vienna. So we need a collecting point, a transit camp. We need Schoenau.”

The Chancellor settled his elbows on the desk, steepled his fingers, looked Golda Meir directly in the eye, and said sanctimoniously, “Mrs. Meir, it is Austria’s humanitarian duty to aid refugees from whatever country they come, but not when it puts Austria at risk. I shall never be responsible for any bloodshed on the soil of Austria.”

“And is it also not a humanitarian duty not to succumb to terrorist blackmail, Herr Chancellor?”

What had begun as conflicting views between opponents was now becoming a nasty cut and thrust duel between antagonists.

Kreisky shot back: “Austria is a small country, and unlike major powers, small countries have few options in dealing with the blackmail of terrorists.”

“I disagree,” seethed Golda. “There can be no deals with terrorism whatever the circumstances. What you have done is certain to encourage more hostage-taking. You have betrayed the Jewish émigrés.”

The man’s brows drew together in an affronted frown. “I cannot accept such language, Mrs. Meir. I cannot

–

”

“You have opened the door to terrorism, Herr Chancellor,” the prime minister spat, undeterred. “You have brought renewed shame on Austria. I’ve just come from the Council of Europe. They condemn your act almost to a man. Only the Arab world proclaims you their hero.”

“Well, there is nothing I can do about that,” said the Austrian in an expressionless voice, looking uncomfortably still. And then, with a hint of a shrug, “You and I belong to two different worlds.”

“Indeed we do, Herr Kreisky,” said Golda Meir, in a voice cracked with derisive Jewish weariness. “You and I belong to two

very

very

different worlds,” and she rose, picked up her handbag, and made for the door. As she did so, an aide to the Chancellor entered to say the press were gathered in an adjacent room, awaiting a joint press conference.

Golda shook her head. She asked herself, what was the point? Nothing she could say to the media could make any difference. Kreisky wanted to stay in the good books of the Arabs

–

it was as simple as that. So, she turned and hissed in Hebrew to her aides, “I have no intention of sharing a platform with that man. He can tell them what he wants. I’m going to the airport.” To him she said contemptuously, “I shall forego the pleasure of a press conference. I have nothing to say to them. I’m going home,” and she exited through a back stairway.

Five hours later she told the waiting Israeli press at Ben-Gurion Airport, “I think the best way of summing up the nature of my meeting with Chancellor Kreisky is to say this: he didn’t even offer me a glass of water.”

As feared, Schoenau was shut down, and for days the Kreisky crisis made international headlines, focusing interest on the question of how the rights of Russian Jewish émigrés could be protected against the outrages of Arab terrorists. Golda Meir’s remonstrations had triggered such an international whirl of protest, however, that the Austrian Chancellor had no choice but to offer alternative arrangements. These were more discreetly administered than the previous ones, and the intermittent exodus of Jews from communist Russia via Austria continued. But the prime minister of Israel was quickly distracted by another and far more urgent crisis on returning home. Intelligence reports indicated large scale Egyptian and Syrian troop movements which her military experts explained away as mere maneuvers

–

a calamitous misinterpretation that swiftly exploded into a war of Vesuvian proportions

–

the Yom Kippur War.

24