The Power of Mindful Learning (16 page)

Read The Power of Mindful Learning Online

Authors: Ellen J. Langer

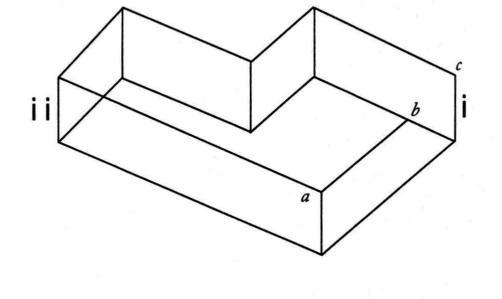

When quickly scanning the right portion of this image

(labeled "i") many viewers see an enclosed structure from a

perspective that looks up from below. The perceptual cue that

the view is from below is the line that runs from a to b but

does not continue to c; one side of the figure appears to be

obscured by another. After then scanning the left portion of

the figure (labeled "ii") several times, many viewers find that

the image appears to flip so that they see the form from

above. Although some viewers are able to voluntarily flip the perspective, most find that a perspective forms without their

thinking about it.

Figure 1 From J. Hochberg, `4ttention, Organization, and Consciousness, "in Attention: Contemporary Theory and Analysis,

ed. D. I. Mostofsky, p. 118 (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts).

Copyright 1970 by Meredith. Adapted by permission.

We depend on this automatic organization of perception

in almost every waking moment. This automatic structuring

of experience generally serves us well by allowing us to interpret our environment almost effortlessly. The limits of this

automatic organization can be seen in the experience with

Figure 1. That many viewers, when focused on the left side

(ii) of the form, are not oriented by the right side (i), indicates

how limited our field of immediate perception can be. We

often fail to keep these limits in mind. Regardless of our initial experience in viewing the figure, we are likely to agree that incorporating this figure into our experience requires no

great cognitive leap. Most of us have a cognitive category,

such as "optical illusion," that allows us to classify the figure

and place it in the general conceptual framework through

which we understand our world. However small this step

from direct perception to a general conceptual framework

may be, it is the first kernel of what we call intelligence.

The ability to place pieces of our experience in relation to

one another was one of the criteria used by Sir Francis Galton,

and later by Alfred Binet, to assess intelligence. In the nineteenth century Galton assessed intelligence by asking people to

arrange a set of weights in order of heaviness, a test of sensory

discrimination that was later adapted in the Binet-Simon

Intelligence Tests Galton also tested people's ability to bisect

lines, a measure later used by James M. Cattell in some of the

first intelligence tests administered in the United States. These

early theorists believed that the basic capacity to organize perceptions was the basis of intelligence. Although Galton and

Cattell's methods of testing perceptual skills were superseded

by psychometric tests that focused on more complex cognitive

tasks, their approach laid the foundation for the assessment of

intelligence.

In the 1870s and 1880s, such theorists as Galton and Herbert Spencer, in addition to Charles Darwin, were applying

evolutionary theory to human behavior.' The link between evolution and intelligence is important, not because of the endless,

and perhaps fruitless, debate about the role of heredity in intelligence, but because the concept of evolution is necessary to understanding the organizing role that intelligence is believed

to have on our perceptions.

Seen in an evolutionary framework, intelligence is an ability

to retain and organize perceptions that enhance our chances for

survival. The perspective we automatically impose on our perceptions is not merely an arbitrary construct, but an adaptive

response determined by natural selection. The more closely our

conceptual map corresponds to the contingencies of our environment, the greater our chances for survival.

In this view, the advantage more highly evolved animals hold

over their less developed counterparts is the ability to take in ever

more subtle perceptual cues and therefore create a more accurate

cognitive map. This general trend toward increasingly fine discrimination, which Spencer' called the "principle of universal

development," was outlined in 1909 by Edward L. Thorndike,

the person perhaps most instrumental in bringing psychometric

(intelligence) testing to the U.S. educational system.

Our bodily descent is roughly as follows: fishes begat

amphibia; amphibia begat reptiles; reptiles begat mammals; some early mammals begat the primates; some early

primates begat man.... [T]he demonstrable intellectual

difference between the year old baby and the monkeys is

not that he has many ideas while they have few or none.

He, too, has few or none. It is that he responds to more

things and in more ways.'

This early conception of intelligence as a capacity for increasingly fine discrimination did not withstand the test of time. By the 1920s, psychologists had demonstrated that basic

measures of perceptual discrimination could not be used to predict such skills as mathematical ability or ability in other academic areas, and mental testing began to focus less on general

intelligence and more on specific abilities.

A mental ability is a probability that certain situations will

evoke certain responses, that certain tasks can be achieved,

that certain mental products can be produced by the possessor of the ability. It is defined by the situations,

responses, products, and tasks, not by some inner essence.'

By abandoning the idea of intelligence as increasingly fine discrimination and defining it instead as a relationship between

specific situations and specific responses, theorists of intelligence

paved the way for what we now call domain-specific intelligence.10 Each domain has its own cognitive map, which an individual can use as a guide to operating effectively in that domain.

The most important task for future theorizing about intelligence is to specify better the interrelations between environmental context, on the one hand, and mental functioning,

on the other."

To understand this notion of optimum fit between individual

and environment, let us try to apply it to our ambiguous Figure

1. Imagine that the figure is no longer a two-dimensional illu sion, but a transparent, three-dimensional model designed to

create a similar visual effect. This glass model is suspended about

twenty yards away. The task is to throw a ball through its center.

We must orient ourselves to this ambiguous form before tossing

the ball through it.

Although such a task may appear fanciful and unrelated to

what most of us think of as intelligence, the standard of optimum fit used by intelligence theorists presupposes that every

pencil-and-paper measure of intelligence implies a real-life

analogue. This imagined task is a specific case of the more general situation confronted by all living creatures: individuals

must use their thinking skills to cope with the environment.

As we have seen, the right side (i) of Figure 1 provides the

critical cue for accurate orientation. The fact that the line

extending from a to b does not continue to c indicates that the

correct orientation is a perspective looking up from below.

Intelligent individuals will recognize this unambiguous cue

(line a-b) and consequently form a mental image that accurately corresponds to reality. Having accurately conceptualized

the figure, these people will have a better chance of tossing the

ball through the suspended form than will those who have an

inaccurate mental image of the figure.

The concept of mindfulness, rather than referring to the ability

of matching cognition to environment, shares with William

James a skepticism of the very notion of correspondence.

Owing to the fact that all experience is a process, no point

of view can ever be the last one. Every one is insufficient

and off its balance, and responsible to later points of view

than itself "

In a mindful state, we implicitly recognize that no one perspective optimally explains a situation. Therefore, we do not

seek to select the one response that corresponds to the situation, but we recognize that there is more than one perspective

on the information given and we choose from among these.

The automatic processes involved in perception may well

result from a long history of natural selection, and, when not

determined by heredity, they probably are conditioned. Mindfulness theory, however, looks beyond these automatic perceptual processes to model higher-level thinking. In a mindful

state, we take a second look at how our perceptions structure

experience on the assumption that they are more malleable

and susceptible to individual control than is apparent at first

glance.

Returning to the ambiguous figure, recall that despite what

appears to be an unambiguous cue at the right side of the figure

(the line extending from a to b but not continuing to c), many

viewers find that their perspective flips involuntarily. If we

believe that the cues in the right half of the form are truly

unambiguous, this slippery perception can be disconcerting. If,

in order to feel in control, we must believe that we have a firm

grasp on reality, the inability to hold this figure stable may be

seen as a failure. Rather than following the implications of this unstable perception, we simply put the experience into a category called "optical illusion" and move on.

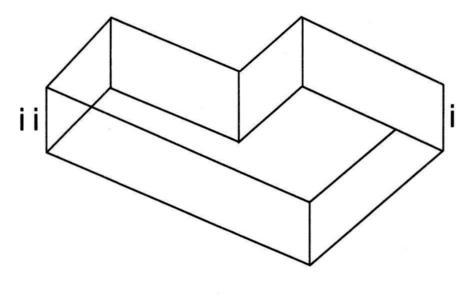

Figure 2 From J. Hochberg, `4ttention, Organization, and Consciousness" in Attention: Contemporary Theory and Analysis,

ed. D. I. Mostofsky, p. 118 (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts).

Copyright 1970 by Meredith. Adapted by permission.

How would a viewer respond if the figure were threedimensional? Imagine that the form now appears as shown in

Figure 2. The contortions presented earlier as an impossibility,

as two conflicting perspectives, now look perfectly reasonable.

This form could be replicated as a three-dimensional object, as

what we call a Mobius strip. After twisting one end of a strip of

paper 180 degrees, Mobius glued the two ends of the paper

together to create a form that twists back on itself so that it has

only one side. By thinking of the form as three-dimensional,

we gain a new perspective.