The Postcard (7 page)

She smiled that same half smile as the first time, tinged now with something like a blush. “Sorry, no. But I do remember a few months ago. You were running like you needed to catch a train. Only there wasn’t any train. It was at Mirror Lake. You were jumping down the library steps, holding a stack of paper like a serving tray.”

I laughed. “Deadline. I’m a writer.”

“What’s your name?” she asked.

“Falcon,” I said. “Nick Falcon. Yours?”

“Marnie Blaine.

“Blaine?” It came to me. “The fat man —”

“My father, Quentin Blaine,” she said. “He owns that hotel, I suppose. And the Gulf Railroad.”

“But only about half of Florida,” I said.

She kept smiling. “Some greyhounds, a hideous new autogyro, and a racehorse or twenty. But really. No more than that.”

Behind her, a man was doing a pretty poor job of pretending to be invisible. He was so much taller than the palmetto he was standing behind that the upper branches might have tickled his chin. The guy was as tall as a house and as lanky as a stovepipe. If he was Mutt, Jeff stood next to him: a little round barrel with a red beard. Too bad there was no fireplug for him to hide behind; he might have had a chance. I’d seen them both before at the hotel when I was nine, only they’d grown. One up, the other sideways.

The giant’s face showed no anger or menace. In fact, there didn’t seem much life in it at all. I thought again of what my father had told me about faces like that. Was he someone else without a soul?

“Maybe this is too risky,” I said, looking at the goons. “Maybe I should send you a postcard.”

I nearly choked. A . . .

postcard?!

She laughed. “A postcard. That’s slightly nuts. What for?”

“With a clue to show you where we can meet. A clue delivered all safe and sound by the U.S. Post Office. I write mysteries, remember?”

She smiled. “I’ll have to read one someday.”

“You’ll be in one,” I said. “I’ll write a story just for you, Marnie Blaine.”

The tall man drifted back into the shadows, satisfied to have seen whatever he was looking for. Redbeard rolled quietly after him. I didn’t like the look of that. Two ghoulish guys making snap judgments, then running off to tell their boss. It was the scenario for a cheap story, and I knew it; I’d written a few of them myself.

“Never mind the postcard,” I said. “The Pier.”

“Daddy keeps his autogyro at the Pier. But you don’t want a ride in it. He’s just learning to drive it.”

“No thanks,” I said. “I leave flying for the birds. And for angels. Like you.” I imagined her at that moment with a pair of bright wings, rose and white and shimmering blue. I liked what I imagined, and it must have shown on my face, because her eyes twinkled.

“I really should be going,” she said. Only she didn’t move.

“The Pier. For lunch,” I said. “And try to ditch the undead.”

“They’re always around. My father likes to know who I talk to.”

“Funny,” I said. “I don’t care who he talks to. Meet me?”

“Maybe I won’t be able to,” she said.

I smiled at her. “Yeah, you will.”

That put a smile on her lips. She walked away then. I followed at a distance and saw her get into a car. It was a cream yellow Phaeton and beautiful. It didn’t have any dents. Its windscreen was the opposite of a cracked one. The thing gleamed like a Roman chariot on race day.

I must have stood there frozen like a garden ornament with a dopey grin, because the driver, a wobbly pole of a guy with a skull for a face, saw me, came over, grasped my arm with fingers of bone, and asked me if I wasn’t forgetting my appointment. When I said I didn’t have an appointment, he offered to make me one with a doctor. I took the hint and hit the bricks.

My stomach told me I needed some eggs.

My heart told me I needed to see her again. I can’t explain it. How could I not want to see Marnie again?

So there I was, dashing down the alley to the sidewalk, and there were the bullets again, going chink-chink-chink at my heels, and all I was thinking about was her.

I nearly made it to the far corner when a shot grazed my calf, and I went down like an arcade target at a state fair. The sedan screeched to a stop a full half inch from my head.

I tried to squirm away into a flower shop, but Redbeard and Mr. Tall weren’t having any. They burst from the car and tackled me before I got to the door.

“Just — a — carnation —” I winced.

The tall man clamped his hammy hand on my mouth. Together, he and the barrel pulled me to my feet, dusted me off, and tried to interest me in a quaint little alley they had in mind.

“You’re real estate agents?” I grunted. “And I could have sworn you were punks.”

That didn’t crack half a smile between them.

“Alley,” the tall one breathed. “Now.”

I said, “I would, but I’m late for my shuffleboard date —” I tried to hobble away, but they were persistent and dragged me into that alley, anyway.

“You’re a credit to your boss,” I said. “By the way, just to be clear, is your boss a fat guy the color of cooked lobster —”

I doubled over when the giant punched me in the gut. His fist was only as big as a battering ram.

To make a long story short, I never did meet Marnie at the Pier, but I did get a chance to ride in that dented blue sedan. It wasn’t the kind of ride they advertise on the radio, all picnic baskets and yodeling kids. The car backed into the alley with us. Skullface swung out of the driver’s seat and sauntered to the back of the car. His oily suit swished in the shadows.

“I tell simple words for you, boy,” he said, as if he had learned how to speak from a book, or a robot, or maybe a book written by a robot. “She there, you not there. She here, you not here. She everywhere, you nowhere. Good. Now I think you understand it, eh?”

“I think I got it,” I said. “Can I go see her now?”

I fell to my knees when he kicked my wounded leg. He kicked me so many times, I couldn’t help noticing that he was wearing yellow socks with little blue anchors all over them. Stylish. I was about to ask him where he shopped when the bearded German grunted, “Enuf. Not here!”

“We’re gonna take you to da post office,” said the giant.

Post Office? Had they read my stories?

“Ya!” chuckled Redbeard. “Vee goink to post you!”

“To where,” I managed to say.

“Everywhere!” said the giant with a laugh.

“You guys been reading Spinoza?” I asked.

I got a final glimpse of yellow sock near my nose before Mr. Skull straightened his suit — all that kicking had rumpled it. He drew a set of car keys out of his pocket, unlocked the trunk, and held it open while the other two goons scooped me up off the ground and poured me inside.

There was something rotten in there that had attracted a few million flies. They were soon done with it, though. I was fresh meat to them.

Just before they slammed down the trunk lid, I heard one of the thugs say, “Gandy.”

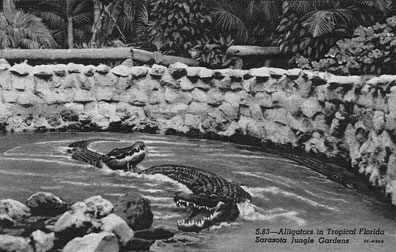

Turns out the real estate men knew something about architecture, too. We were going to Gandy Bridge. I guessed their “post office” was an underwater branch, and the posts they were talking about were the concrete ones that supported the bridge. They were going to tie me to one and hope that the fish and maybe an alligator or three would eliminate the evidence.

We drove off at high speed. In the dark of the trunk, I imagined the turns between downtown and the bridge. I remembered that feeling of sand under the tires just before you hit the bridge. The sedan would have to slow a bit or shimmy on the highway. It would be my last chance to escape before they pulled off the road and carried me down beyond the scrubby palms and sand to where the posts were. There wasn’t much time.

My legs were like stalks of pain. My eyes burned. My lungs felt like lead. My nose was filled with the stink of something dead, and I wondered if I was smelling my own future. I decided not to dwell on it. I slipped off my belt and started working on the lock with the prong of the buckle. The sedan tore through the streets, fast, fast. After a while, we jerked right; then I felt the tires tearing over sand. They slowed. Then —click — the lock opened.

“Timing!” I whispered. Edging the trunk up, I jumped out, hit the ground, and rolled clear just as the car picked up speed again and bounced off into the shadowy undergrowth.

I looped my belt back on and took off as fast as my sore legs could carry me. With my wounded calf, it wasn’t all that fast, but for the moment I was alive and free. How long I would be either was anyone’s guess.

End of Chapter I

I was quaking all over, barely able to breathe. Grandma’s boyfriend had written this story. A guy named Nick Falcon met a girl named Marnie in my great-grandfather’s hotel. The funeral guy had called Grandma “Marnie.” I saw the posts under the Gandy Bridge. I saw the tall man and the short German. Was this a story based on things that really happened? Would Dad know?

Would he tell me?

I wondered, of course, whether Emerson Beale could be Dad’s father. He was Grandma’s boyfriend, after all. But Dad said Beale went away long before he was born. I wanted to read the story again — every word — but before I could turn back to the beginning, I saw a small box outlined in black at the bottom of the last page.

A Note from the Editors

Chapter II of “Twin Palms” would have appeared in the next issue of Bizarre Mysteries

.

It is our sad duty to report that Emerson Beale was killed in action on the island of Saipan in June of this year. His passing will be mourned. It is to his memory that we dedicate his unfinished story.

I stared at the black box. My heart thudded, then skipped. My throat was thick. I couldn’t swallow.

He died? Emerson Beale died?

His passing will be mourned?

I felt as if I had been kicked in the chest. Whatever thoughts I had about who Dad’s father might have been couldn’t include Emerson Beale anymore. He died in the war almost twenty years before Dad was born.

But even more amazing was what I found written in the margin of the last page. In thin blue ink, in neater penmanship than I have ever seen, were words in what I knew was my grandmother’s handwriting:

your Marnie forever

So that pretty much confirmed it. Grandma was Marnie. If Emerson Beale was Nick Falcon, he had been good to his word. He had written a story for her. Only it was a story with no ending.

I took up the postcard again and began to study it. Could there have been a clue on it, as Nick said in the story? Was that what the caller wanted me to find? I turned the card over and stopped short. I read the postmark again.

1947.

Emerson Beale died in 1944.

I stood up and paced the room. “The card couldn’t have been from him,” I said to myself. “He had been dead for three years before it was sent. So who sent it? And why was it hidden that way in the desk —”

I heard the sharp sound of scraping metal outside the back door and then a yell.

“No —!” my father cried. “Oh, Gawww —”

I jumped into the kitchen in time to see the ladder slide down across the back of the house followed by a deep

thump.

“Dad!” I cried, rushing out the back door.

The ladder was lying across the bushes. My father had fallen off the house and hit his head on the concrete patio.

“Dad!” I said. “Dad!” He was doubled in half and not moving. “Dad!”

For what seemed like hours, he didn’t move. Then he blinked his eyes and swore. “Holy —!” I was never so happy to hear him curse. “Dad, are you okay?”

He swore again. “No . . . oh, man . . . Jason . . .” He let his head settle back onto the patio, moaning and clutching the side of his face. One of his ears was bleeding from the inside.

“It’s okay. Don’t move so much.”

Mrs. K’s door opened, and she came out, her arms full of wet laundry. She was humming. When she saw us on the ground, she screamed.

“Call 9-1-1!” I said. She turned this way and that, then finally dropped the wet clothes on her stoop and scurried inside.

Dad rolled over the corner of the patio onto the grass, clutching his head until he went still, blinking his eyes at the weird angle of his left leg. It was bent in a way that looked like a cartoon character might be able to snap it back into place, but not a person. He looked for a while at his leg, groaned weirdly, then sank bank.

“Oh, gawww . . . oh, jeez . . . Jason . . .”

“Don’t try to talk,” I said. “An ambulance is coming.”

“I called them!” said Mrs. K, stepping through the side yard. “A few minutes is all —”

She was right. It wasn’t long before I heard the siren and again not long before the ambulance screeched into the driveway. Two women rushed around to the back with a couple of packs. They twisted Dad carefully into a more or less normal shape, him yelling with each small movement, then lifted him onto a collapsible gurney a man brought around. They strapped Dad’s head tightly with braces and Velcro straps. Mrs. K was clutching my arm the whole way around the side yard to the van.

“St. Pete General,” said a medic, and one of the women hopped behind the wheel. A police car drove up now. An officer jumped out and helped the others slide the gurney into the van.

“You’re going, too?” the policeman asked me. Before I could answer, he asked, “Where’s your mother? Is she here?”

“In Boston,” I said.

“What? Boston?” he said, slipping the radio from his belt.

“Get in!” said the man in the back of the van.

“I’ll meet you at the hospital,” said Mrs. K.

My legs took over, and I headed for the van. Before I got in, I glanced back at the front door of the house.

“Never mind that!” said Mrs. K. “I’ll lock up the house. I have a key —”

“Grab your father’s wallet first,” shouted the officer, running to his car.

The next hour was a blur of streets and sirens, then doctors and nurses and slamming doors and ramps and running through hallways, until it all stopped and a doctor met me outside the emergency room and told me Dad had a concussion, bruises on his shoulders, and his shin bone was fractured.

“He was drinking, I guess?” the doctor said. “And he fell off the ladder onto a concrete patio?”

I tried to take it all in. I nodded. “He had a little, I think.”

“More than a little,” he said, glancing at his clipboard. “He’ll be here for a few days. Is Mrs. Huff around?”

I looked blankly at him, thinking for a second he was talking about my grandmother.

“Your mother?” he said. “Is she here?”

My mother never called herself Huff. She had kept her maiden name. She was Jennifer Gampel.

“No,” I answered.

“Your dad is awake now. For a little while. When will she be coming? Soon? Did you call her? Do you want us to call her?”

“No, I mean, she’s not in Florida,” I said, suddenly worrying if this was a problem.

The officer came in then and came over to us, and the doctor said, “We might have to call Family Services.”

Family Services. It actually sounded like something we could use.

“No, no,” I said. “I’m just down here with my father from Boston for a little bit. My grandmother just died.”

“All right, look. Your father’s going to be here for three, four days at least before he can come home. I’d like you to call your mother,” said the doctor. “Come over here.” He was kind of snippy, as if he had more important things to do. He stepped to the emergency counter, where the desk phones were. The officer followed us. It was all going so fast, but the moment I looked at the phone it flashed through my mind what would happen when I called.

Mom would just pull me out of here. Even if she cared about Dad, she’d be so mad, she’d yank me straight back to Boston, leaving him in the hospital. Then he’d slink back when he got better, and the silences and icy comments would quickly explode into a final argument, and we’d split up completely.

I hated this place, this stupid heat, the smells, and all these nutty old people and dead bodies, but I couldn’t forget the way Dad was at the funeral. He was sad. He was miserable and sad and had too much to drink and hurt himself. So okay. He wasn’t drunk all the time. And the yelling and breaking stuff? Okay, I was stunned, but I got it. He wasn’t a psycho. He’d never done that kind of thing before. His mother just died.

Besides, I could probably stay with Mrs. K, right? Of course. She’d want me to. She would be there soon. I was hoping she would be enough for them, the police. She seemed nice, if a little cracked. I could stay with her.

But Mom? Maybe if things got worse, a lot worse, I’d tell her what happened. But now? No. If she came now, she’d mess it up. She’d push and push then bring me home. And why? So she could leave on another trip?

No, keep it simple. Say nothing. Talk to Dad first about everything. It was only a few days!

All this flashed though my mind in a few seconds, and I knew right then that I was about to do something really serious, but that I was going to do it, anyway. “I’ll call her right now,” I said, glancing at my watch. “She’s at work.” I put my hand into my pocket and, making as small movements as I could, I turned off my cell phone.

Why was I doing this? They’d know, right? They’d know.

The nurse at the desk smiled and slid a phone toward me as she handed me back my dad’s wallet and a plastic bag of his stuff. “Sure. Dial nine, then the area code. Here.” She pressed a button on the phone.

The doctor and the officer were looking at me, talking, and doing a lot of head wagging. I tapped in the number slowly then turned away. The phone rang on the other end.

“Uh . . . hi,” I said.

“Dude! Is it raining yet?”

“Look, Hector, I’m in the ER with my dad,” I said quietly. “He fell off a ladder.”

“What the heck?”

“I know, but everything’s okay for now. And he’ll be out of here before you know it. Look, they think I’m calling my mom, but I can’t do that yet. But don’t tell anybody. Not your mom. And definitely not my mom.”

“How about nobody’s mom?” he asked.

“Perfect.”

“Heck, dude, the ER. I hope he’s okay. But look, especially be careful to make no eye contact there. I mean it. The patients are, like, halfway across.”

“I know, but it’s okay for now. I gotta go.”

Mrs. Keefe was standing in the waiting area when I got off the phone, and I asked her if I could stay with her for the next few days.

“Of course, dear. I’ve already talked with the officer,” she said. “I have ice cream and plenty of tuna fish.”

The doctor saw us talking, then shared a look with the police officer. They both gave me a look. I told them that my mother would call back a little later; she was at the airport for another flight, but would get here as soon as she could. Until then, I’d be at Mrs. K’s house.

The officer relaxed. “Okay. Could I have your mother’s cell number?”

“You can’t call her now because she’ll be in the air,” I said.

“Fine, but for later,” he said.

Gosh, what a little creep I was. I told him her cell number with the last two digits reversed. He jotted it down. He likely wouldn’t use it for a while at least. By then, I’d be back at the house, and things could have changed, anyway. I could always say I got the numbers mixed up because I was upset about my dad getting hurt.

“Okay,” he said.

I tried not to lie, really. It was more like bending the truth. To say something that wasn’t exactly a lie, but wasn’t the whole truth, either; that was hard. But I felt I had to give Dad a chance here. Mom was waiting for him to drink too much and to mess up, and he had done both. But it wasn’t so bad, was it? It wasn’t as if he had had a car accident. He had only hurt himself. And it was just for a few days. We could get past this.

“You can go in now,” said the doctor, and he turned and walked briskly down the hall.