The Portable Veblen (3 page)

Read The Portable Veblen Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mckenzie

And he didn’t realize she hadn’t graduated from college either. That embarrassed her, and was probably something he should find out soon. It simply hadn’t come up. Since when you marry you are offering yourself as a commodity, maybe it was time to clear up details of her

product description

. Healthy thirty-year-old woman with no college degree. Caveat emptor

.

In spite of her cheerfulness in the presence of others, one could see this woman had gone through something that had left its mark. Sometimes her reactions seemed to happen in slow motion, like old, calloused manatees moving through murky water. At least, that’s how she’d once tried to explain it to the psychiatrist who dispensed her medications. Sometimes she wondered if she had some kind of processing disorder. Or maybe it was just a defense mechanism. One could see she was bruised by all the dodging that comes of the furtive meeting of one’s needs.

• • •

F

OR SEVERAL YEARS

before meeting Paul, Veblen had steered clear of romantic entanglements, haunted by runaway emotions and a few sad breakups in the past. “No one will ever understand me!” she often cried when feeling sorry for herself. Sometimes it was all she could do not to bite her arm until her jaw ached, and take note of how long the teeth marks showed. She had made false assumptions in those early experiences, such as that love meant becoming inseparable, and a few suitors came and went, none of them ready for all-out fusion. She began to realize she hadn’t been looking for a love affair, but rather a human safe house from her mother. A legitimate excuse to be busy with someone else. An

all-loving being who would ever after uphold her as did the earth beneath her feet.

She came to recognize her weaknesses through these trial-and-error relationships, and lament that she had them. In a tug-of-war of want and postponement she continued with her deeply romantic beliefs, living in a state of wistful anticipation for life to become as wonderful as she was sure, someday, it would.

Veblen’s best friend since sixth grade, Albertine Brooks, smart and training as a Jungian analyst in San Francisco, had been alarmed by the sudden onslaught of Paul: Veblen, she felt, had unprocessed shadows, splitting issues, and would be prone to animus projections and primordial fantasies with destructive consequences. But Veblen only laughed.

Over the years, they had discussed, almost scientifically, the intimate details of their romances—for Veblen starting with Luke Hartley in the back of the school bus returning from a field trip to the state capitol. Sure, he’d paid heaps of attention as they marched through the legislative chambers, standing close and gazing raptly at her hair, even plucking out a leaf. Sure, he asked her to sit with him on the bus. Yet it wasn’t until the last second, when he touched her, that she believed he might have feelings for her. She told Albertine about his milky-tasting tongue and roaming, hamsterlike hands, and then Albertine prepared her for the next step, of unzipping his pants. And with Albertine’s pragmatic voice in her ear, that’s what she attempted next time she and Luke were making out on the athletic field after school. A difficult grab under his weight, shearing her skin on the metal teeth—as she grasped his zipper he pushed her away and groaned, “Too late.”

Too late? Wow. You had to do it really fast or a guy didn’t want anything to do with you. She pulled away, staring dismally over the grass, a failure at love already.

But Albertine said later, “No, you dummy. He meant he’d already ejaculated!”

“Huh?”

“What were you doing right before?”

“Just rolling on the lawn, kissing.”

“Okay, exactly.”

“You mean—”

“Yes, I mean.”

“Oh! So that’s good?”

“Good enough. It could have been better.”

In that instance, Albertine helped Veblen overcome her habit of assuming fault when someone said something cryptic to her.

“So you think he’s still attracted to me?” she asked.

“Yes, Veblen.”

“Wow. I thought it meant I blew it.”

“He

wished

you blew it.”

Veblen wrinkled her nose. “But you don’t actually

blow

on anything, do you?”

“No,” said Albertine, pityingly.

Albertine had, for her part over the years, partaken of a number of gritty encounters that had led to a surprising lack of heartbreak. Veblen could never dive in with someone like that and not feel anything. She’d always admired Albertine, who put her ambitions before her family or guys, and didn’t cling to anybody but Carl Jung.

She frequently lent Veblen books to help with her psychological

development, but none of them seemed to address the central issue: Veblen’s instinctive certainty that the men who asked her out would not understand her if they got to know her better.

Then along came Paul. Little more than three months ago they had been strangers at the Stanford University School of Medicine, Veblen a new office assistant in Neurology. There, every morning, she took to her desk wedged between the printer and the file cabinet, threw her bag into a drawer, pulled out her chair, logged in. Horizontal ribs of light flickered across her desk, signaling her last allotment of morning. Later the sun would hit the handsome oak in the courtyard and make its sharp leaves shimmer. In between, she’d harness her fingers and drift away, typing up the minutes from the Tumor Board or a draft of one of the doctors’ professional papers or case notes. She was amazingly good at

dissociating,

alleged to be unhealthy, but which she had found vital to her survival over the years.

Across the office sat Laurie Tietz, a competent, muscular woman of forty with a pursed mouth that looked disapproving at first, but really wasn’t. Veblen felt uncomfortably watched the first time Paul stopped by to see her, but no, it was only the set of Laurie’s lips. Veblen liked her, despite being captive to her daily conversations with her husband about their home improvements and shopping lists. “Pick up some cheese and light bulbs today, don’t forget. Love you.”

That was the part she hated—when Laurie said “Love you.”

Dr. Chaudhry would arrive carrying his briefcase and a Tupperware tub filled with snacks made by his wife. He was a small, quiet man with large round eyes, a shaggy mustache covering his lips, slightly bent aviator glasses, and broken embroidery

sticking up like ganglia from the fabric of his white coat.

Lewis Chaudhry, MD

.

From her desk on any given day, she could see squirrels hurling themselves through the canopy of the trees, causing limbs to buckle and sweep. She started to realize that squirrels were the only mammals who lived right out in the open near humankind.

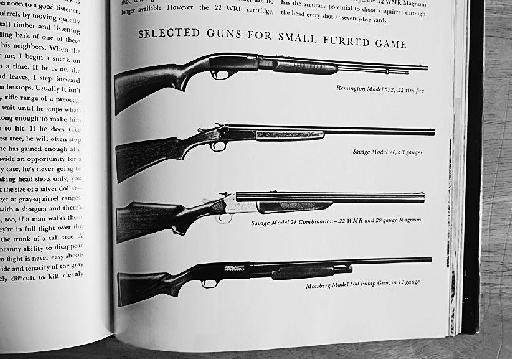

SELECTED GUNS FOR SMALL FURRED GAME.

Despite this aura of neighborliness, recipes for squirrels were included in the

Joy of Cooking

. Was this a curious case of misplaced trust?

That was the day Chaudhry approached her with a manila envelope—the “envelope of destiny” she and Paul came to call it.

“Do you know where to find the research labs?” Chaudhry asked her.

“Sure.”

“Find Paul Vreeland. Then tell him the road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

Veblen raised her eyebrows. “Wouldn’t that be kind of—awkward?”

“Tell him it’s coming from me.”

She still wasn’t crazy about the idea. “Why? What did he do?”

“He had a great opportunity here and he’s throwing it away.”

“Gee, that’s too bad.”

“He is not the first,” Chaudhry said.

That hall, with its sharp smells and vibrations and a high number of bins for hazardous waste, was unknown territory for her. At last someone directed her to Vreeland’s lab, and she entered after knocking a few times without response. Curled over a buzzing table saw, with his dark hair hanging over his safety goggles, he looked every bit a mad scientist absorbed by his master plan.

“Dr. Vreeland?” She cleared her throat. “Hello? Excuse me!”

Her nostrils contracted from the stench of singed flesh. Maybe she tottered or blanched. He glanced up and ripped off his goggles, his elbow sending a row of beakers off the table while the saw screeched on, spraying a curtain of red mist onto his lab coat and the wall.

“Oh shit!” Glass snapped and crackled under his soles as he threw the switch on the saw and covered the gory mess with a blue apron. An ominously empty cage sat atop the stainless steel slab. “Sorry, I didn’t hear you come in. God.”

“Yeah, sorry, I knocked, I wasn’t sure—”

He insisted it was his fault, not hers, he didn’t mind that she came in, hours would go by when no one came in, he’d get wrapped up and forget the time, and when she asked what he was doing he began to explain his work, mentioning apologetically that small

mammals were suited to neurological research because one could easily expose the cortex, apply special dyes or probes or electrodes directly, to observe the activities of neurons and test for humans, and in his case, for the men and women of the armed forces, who needed breakthroughs fast.

“Basically I’m moving toward a breakthrough for brain injury treatment,” he concluded, smoothing down his hair, and it was at that moment she realized how adorable he was. “I’m a little obsessed right now. I dream about it at night.”

“Is that all you dream about?” she asked.

He might have blushed. “Well, maybe I need a new dream,” he said, with an endearing look on his face.

“

Oh, well. Sorry to cause such a ruckus,” she said, wondering why she had to sound so weird. Who said

ruckus

these days? “It was for this,” she said, handing him the envelope.

“Oh, from Chaudhry. Finally.”

As he glanced into the envelope, she picked up the product literature for the Voltar bone band saw.

“Wow, are these features really great or something?”

“What features?”

She read them off:

“Diamond-coated blade has no teeth and will not cut fingers! Cleans up quick and easy! Wet blade eliminates bone dust! Splash guards and bone screens included!”

“It’s always a little shocking to see the commercial underbelly of research,” he agreed. He had dimples, and friendly eyes. “There’s this whole parallel consumer reality in the medical and defense industries; it takes some getting used to.”

And right there, Veblen had been lobbed one of her favorite topics: the gargoyle of marketing and advertising. “I believe it. But

what’s weird about this—marketing is supposed to kindle the

anticipatory daydream,

supposedly the most exciting phase of acquisition. But here, what would be the daydream?”

“Freedom from bone dust, of course—which is very exciting. Look at this thing,” he added, springing over to open a drawer from which he removed a two-and-a-half-inch disk that resembled the strainer for a shower drain. “This is the titanium plate we screw on after a craniotomy.”

“Oh, really?” From the sleeve she read:

“Reconstruct large, vulnerable openings (LVOs) in the cranium! Fully inert in the human body, immune to attack from bodily fluids! Cosmetic deformity correction to acceptable levels!”

They both laughed nervously.

“Weird. Are ‘large, vulnerable openings’ so common they need an acronym?” she asked, suddenly blushing.

“Um, yes, as a matter of fact, they are.”

“Oh.”

“And it’s good,” he added.

“Why?”

“Well, I mean, if the LVO is the result of a procedure to improve the condition, then it’s good.” He tossed the plate back into the drawer, and went to the sink to wash his hands.

“I’ve seen those at the hardware store for about ninety-five cents,” Veblen said.

“Try between two and three thousand for us.”

“That’s crazy!”

“Yeah. So. I was about to take a break. Want to get something in the café?” he asked, looking away.

“Oh? Sure, why not.”

They had coffee and oatmeal raisin cookies together, on the palm-potted atrium where the staff went for air. This was early October, warm and bright. Veblen wore a thin sweater inside the hospital, but peeled it off, conscious of her freckly arms, wondering if the invitation to the café meant he liked her. She was still afraid to assume such things.

“What do you do here?” he asked.

“Administrative-type stuff,” said Veblen. “I move around. I was in Neonatology for a year and a half, Otolaryngology almost three years, and this is my third week in Neurology.”

“Are you—going into hospital administration?”

“No, this is just for now. I do other stuff, like I’m pretty much fluent in Norwegian so I do translations for this thing called the Norwegian Diaspora Project in Oslo.”

“Wow, that’s interesting. Are you Norwegian?”

She was Norwegian on her father’s side, and further, she’d been named after Thorstein Bunde Veblen, the Norwegian American economist who espoused antimaterialistic beliefs and led an uncommon and misunderstood life. (A noble nonconformist. A valiant foe of institutions and their ossified habits of mind.) The Diaspora Project had a big file on Thorstein Veblen, and thanks to her, it was getting bigger all the time.