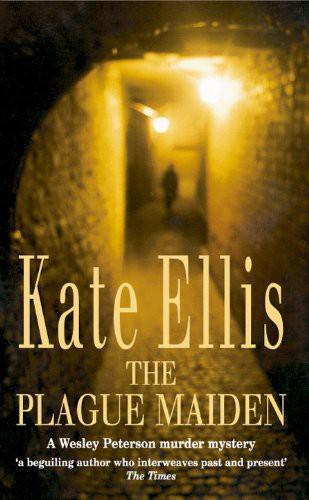

The Plague Maiden

Kate Ellis was born and brought up in Liverpool and studied drama in Manchester. She has worked in teaching, marketing and

accountancy and first enjoyed literary success as a winner of the North West Playwrights competition. Keenly interested in

medieval history and ‘armchair’ archaeology, Kate lives in north Cheshire with her engineer husband, Roger, and their two

sons.

The Plague Maiden

is her eighth Wesley Peterson novel.

The Merchant’s House

,

The Armada Boy

,

An Unhallowed Grave

,

The Funeral Boat

,

The Bone Garden

,

A Painted Doom

and

The Skeleton Room

are also published by Piatkus.

The Merchant’s House

The Armada Boy

An Unhallowed Grave

The Funeral Boat

The Bone Garden

A Painted Doom

The Skeleton Room

Published by Hachette Digital

978-0-748-12669-9

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public

domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely

coincidental.

Copyright © 2004 by Kate Ellis

The moral right of the author has been asserted

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior

permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

To Ruth Smith and Pat Grigg with many thanks for their

patient reading and their honest advice

September 1991

The intruder stood quite still and listened. But he heard nothing: no voices, no distant babble of a television or radio,

no creaking of boards on the floor above. It seemed that he was quite alone … except for the lingering, blood-scented presence

of death.

From time to time the noises of the country night pierced the deep silence; a screeching owl, a barking fox, the mournful

lowing of a discontented cow in a nearby field. The intruder shuddered. The sounds of the countryside were frighteningly unfamiliar,

not like traffic or the chatter of pub voices.

As he walked on tiptoe into the hallway he noticed that a door to his left was standing open to reveal a large shabby room,

bathed in the jaundiced light of a tall standard lamp. He hesitated on the threshold before creeping in, his heart beating

so strongly that he could hear the blood pounding in his ears. Stopping by the faded chintz sofa, he gazed for a few seconds

at the framed photograph on the mantelpiece – a pale image of a woman cradling a tiny baby. But after a quick glance around

he decided it was time to move on. He might have more luck upstairs.

The intruder climbed the stairs, and when he reached the landing a brief tour of inspection only confirmed what he already

suspected … that the house’s occupant was more interested in books than in material possessions. Every shelf and surface was

crammed with the things, all dull scholarly works with titles such as

Theology Understood

and

Wessler’s Principles of Biochemistry

. The intruder had assumed that a big house in a place like Belsham would

provide rich pickings for the casual thief. But you could never judge a book by its cover.

In the main bedroom – a room furnished with almost monastic simplicity – he spotted a shabby leather wallet lying on the bedside

table and he pocketed it quickly before making his way back downstairs by torchlight. It wasn’t much but he supposed it was

better than nothing.

He crept back into the room where the French window stood ajar, its lock splintered where it had been forced open. But the

unexpected sight of a man’s corpse, lying half hidden behind the cluttered desk in the centre of the room, brought him to

a sudden halt.

As soon as he saw the staring eyes and the mess of battered skull beneath the blood-matted grey hair his hand went to his

mouth. The seeping blood had spread outwards and soaked into the patterned carpet, staining the dead man’s snowy-white clerical

collar a rusty red.

The intruder felt a wave of nausea rising in his gullet and he knew that he had to get out of that place of death before he

was sick. Although his legs felt unsteady, he took a deep breath and hurried past the mortal remains of the Reverend John

Shipborne, his eyes fixed ahead.

And as he stepped through the French windows, out into the still country night, he was quite unaware that he was being watched.

I thought little of it when William Verlan asked me to help one of his PhD students research the history of Belsham in the

middle of the fourteenth century. I’m used to visitors looking around the church, asking their questions, and I usually smile

sympathetically and hand them a guidebook

.But I can hardly fob Barnaby Poulson off with a potted history of the place, can I? He wants to dig deeper and uncover more

than the bare facts

.He tells me that he has discovered some old manuscripts in the archives at Exeter and he hopes they’ll yield valuable information

about Belsham’s past. His particular field of interest appears to be the Black Death of 1348

.I confess that I’m beginning to regard Poulson’s frequent visits to the church and his constant questions as a bit of a nuisance

.From a diary found among the Reverend John Shipborne’s personal effects

The jar of jam was taken from its clean white carrier bag and held at arm’s length. There must be no fingerprints – no clues

– and the damage to the seal must be undetectable. This job had to be done properly.

The jam was Huntings’ own brand, new and unopened, and when the carpet of crumbs had been brushed aside, the virgin jar was

placed on the table next to a slice of half-chewed toast and a cracked mug containing muddy dregs of coffee: the squalid remains

of a hasty breakfast.

The ancient fridge in the corner of the kitchen had been salvaged from a skip but it still worked after a fashion. The fridge

door was opened to reveal a trio of shrivelled vegetables, a bottle of milk and a packet of ham just past its sell-by date.

Beside the ham lay a small glass dish with a glass cover, an object more suited to a laboratory than a kitchen.

Hands encased in blue rubber gloves lifted the dish off its filthy wire shelf and carried it over to the table, where a white

carrier bag bearing the words ‘Hunt for good prices at Huntings’ was smoothed out, waiting.

It was time to get to work. Time to spread death.

‘It’s called Pest Field.’

‘Does anyone know why?’ Neil Watson looked around the field, his eyes drawn to the roofs of the new executive homes that peeped

over a hedge a few hundred yards away.

Dr William Verlan scratched his balding head and looked slightly embarrassed. He was a tall man with a neat moustache and

a trim, muscular build that suggested he kept himself in shape. He spoke with a soft American accent and his clothes looked

as though they’d been taken straight from the retailer’s shelves. But in spite of the immaculate appearance there were telltale

dark shadows beneath his eyes: he looked tired. ‘I’ve been taking a year’s sabbatical and I only got back from the States

on Saturday,’ he said defensively. ‘I didn’t hear about your dig until this morning. If I’d known about it I could have done

some research.’

Neil shuffled his feet impatiently. They were working to a deadline and he hadn’t come to hear excuses. ‘I read somewhere

that there was supposed to be a leper hospital around here.’

Verlan blushed. ‘I’ve heard that too but … ’

‘Well, a medieval leper hospital shouldn’t be too hard to find,’ said Neil, pulling his green wellington boot out of a cow

pat with a satisfying squelch. ‘If it’s an important site we might even be able to halt the wheels of commerce for a little

while.’ He grinned as though this prospect pleased him. Dr Neil Watson, field archaeologist for the County Archaeological

Unit, was only too aware of his own mildly anarchistic tendencies. ‘I’ll get the team up here later on to do a geophysics

survey. That should tell us if there’s any sort of building under here … with any luck.’

He shielded his eyes against the sun and studied the squat church tower protruding above the hedgerow not far from the new

executive homes. The old village of Belsham – a settlement that had once earned itself a mention in the Doomsday Book – was

being swallowed rapidly by the spreading suburbs of Neston.

He looked at Verlan, who was standing beside him looking rather nervous. He taught medieval history at Morbay University and

there was no harm in picking his brains.

‘What do you know about the church?’

‘It’s the parish church of St Alphage. Most of it dates from 1276 and the chancel was added in 1424.’

At least Verlan seemed to know his dates. ‘Worth a look?’

Verlan shrugged. Neil waited for some comment about the church, its architecture, its history or the quirky little features

that, in his experience, each ancient church could boast. But Verlan remained silent, his long, pale face unreadable. With

his inscrutable expression and his small, dark eyes he reminded Neil of a watchful lizard. But perhaps he was being unfair.

The man had only just got back from the States – perhaps he was still feeling the effects of jet lag.

‘Fancy showing me around?’

Verlan looked at his watch. ‘I haven’t time right now. I’m teaching in an hour. I seem to recall there are some

interesting tombs in the tower but it was closed off years ago for safety reasons.’

‘So it’s dangerous?’

‘It was locked up in the early nineties and it’s not been opened since as far as I know.’

‘You lived in Belsham long, then?’ As Verlan was American somehow Neil had assumed he was a relative newcomer.

Verlan smiled. ‘Over twenty years now. My father was stationed over here during the Second World War and he used to talk about

how beautiful Devon was so when I had the chance to come over here to teach, I took it.’ He suddenly frowned. ‘When are you

starting to dig?’

‘As soon as we can. We’re working to a deadline so there’s no point in hanging about. Maybe you can show me the church some

other time, eh?’

‘Maybe.’ There was little enthusiasm in his voice.

Neil Watson stared at the mellow stone tower, resolving to investigate it himself if he got the chance. But time was tight

and the next branch of Huntings supermarkets would be built on this site in due course, whatever his team discovered beneath

the earth.

Verlan turned and began to walk towards the gate that led out onto the main road. Neil watched him go, thinking his behaviour

had been a little odd. Perhaps William Verlan didn’t like hanging around old churches, which would be unusual for someone

who claimed to be interested in medieval history. Or maybe there was some other reason. From the expression on Verlan’s face

it was clear that something was worrying him.

The West Morbay branch of Huntings stood on the sprawling outskirts of the ever-expanding resort town, in the unlovely scrubland

where the town was nibbling at the country as the sea nibbles at a beach when the tide flows in; relentless and unstoppable,

even by the toughest-minded official in the local planning department.

Unlike its neighbouring DIY superstore – a monolithic construction in grey corrugated iron – Huntings had at least tried to

ensure that their store didn’t offend the eye. Its architect had taken his inspiration from a picture of a Roman villa in

his daughter’s school history book and had considered the style so pleasing that every branch of Huntings had ended up with

neatly pitched roofs and elegant columns that would have gained the approval of any Roman matron with an eye for contemporary

architecture.

Inside the supermarket Keith Sturgeon, the branch manager, sat in his office at the back of the building. Or offstage, as

he liked to think of it.

He held a small mirror in his left hand and smoothed down his wiry hair with his right, frowning at the silver hairs that

were encroaching on the brown. It was nearly time to go onto the shop floor. Keith used his office as an actor uses his dressing

room, somewhere to prepare for his public appearance. It was here he ensured that his appearance was immaculate, that no hair

was out of place and that the flower – newly plucked each morning from the reduced bunches of flowers that, having reached

their sell- by date, stood in green plastic buckets by the supermarket entrance – stood pertly to attention in his buttonhole.

He stood up and performed a final check on his appearance in the full-length mirror near the door. It was time to go down

and show his face to his staff, like a general riding before his troops prior to a battle. Then he would tour the aisles and

greet his public. The personal touch was important, especially in a supermarket. He looked at his watch. Ten o’clock. It never

occurred to Keith that his staff were aware that he did his grand tour at the same time every morning and were fully prepared

for his inspection. The thought of introducing the element of surprise and varying the time to keep them on their toes never

crossed his mind.

He glanced back at the monstrous stainless-steel creation sitting proudly on his desk. The Manager of the Year

award … the highlight of his career. But that had been twenty years ago and that early promise hadn’t transformed itself into

the promotion he had expected … and at one time craved. Now he had to be satisfied with his wife bringing home the lion’s

share of the household income. Her golden career, uninterrupted by childbearing, had flourished while his had stagnated. But

there was nothing else to do but carry on.

There was a knock on the office door and Keith uttered what he considered to be an authoritative ‘Come in’. The door opened

and a young Asian woman entered the room. Her glossy, raven-black hair was swept back into a neat ponytail, and the only thing

that stopped her from being a stunning beauty was an over-large nose. She wore a businesslike navy blue suit and held a pile

of open letters in her left hand.

Keith straightened his back. ‘Come in, Sunita. I was just going down on the floor. Is that the post?’

‘Yes. It gets later every morning. There’s nothing urgent. Shall I leave them on your desk?’

‘Thank you, Sunita.’

She placed the letters on the desk, keeping back one unopened envelope. ‘This one’s marked strictly private so I didn’t open

it.’ Their fingers touched as she handed the letter over and Sunita withdrew her hand quickly.

Keith examined his watch. Five to ten. Just time to see what the long envelope with the neatly hand-printed address contained.

He tore it open while Sunita hovered in the doorway, curious. She watched as he read the letter inside and saw his face turn

deathly pale.

He looked up at her with panic in his eyes, and as he slumped down in his chair the flower fell from his buttonhole onto the

carpet.

Detective Sergeant Rachel Tracey leaned forward and her blouse gaped open, revealing a glimpse of the scanty white lace bra

beneath. Detective Chief Inspector Gerry

Heffernan scratched his tousled head and stared for a few seconds before averting his eyes, feeling a little embarrassed by

his fleetingly impure thoughts. He was getting too old for that sort of thing, he told himself firmly; and besides, it wasn’t

good for his blood pressure.

‘This has just arrived in this morning’s post, sir. It’s addressed to a Chief Inspector Norbert. Do you know …?’

‘Someone’s a bit out of date. The poor sod had my job many moons ago … before your time.’ He frowned. ‘Open it and read it

to me, will you.’

Heffernan, a large, untidy man with a prominent Liverpool accent, leaned back in his sagging black leather chair with his

hands behind his head in an attitude commonly reserved for sunbathing.

Rachel brushed a strand of fine fair hair off her face, opened the envelope neatly and cleared her throat. ‘It says “Dear

Mr Norbert”’ … She hesitated.

‘Go on.’

‘“Dear Mr Norbert, I wish to inform you that there has been a great miscarriage of justice.”’

Gerry Heffernan snorted, opened his eyes and raised them heavenwards. ‘Which innocent man are we supposed to have banged up

this time?’

Rachel assumed the question was rhetorical and continued to read. ‘“I would urge you to look again into the case of Chris

Hobson. I know he is innocent but I had a very good reason for not coming forward at the time. When I saw him on the television

… “’

‘Television? What was he on?

Crimewatch

?’

Rachel smiled. ‘No, sir. He was on that series …

Nick

, it’s called … a fly-on-the-wall documentary about life inside a prison. My mum watches it,’ she added, slightly disapproving.

‘So they’re giving villains their own TV shows now, are they?’ Heffernan shook his head in disbelief at the topsyturvy nature

of the modern world. ‘What else does it say?’

Rachel read on. ‘“When I saw him on television I felt I

should write to you. I know it’s a long time ago but I beg you to look into Chris’s case again.”’ She looked up. ‘That’s all.’

She handed the letter to Heffernan, who took it by the corner, as if it were something contaminated, dirty. ‘It’s signed “J.

Powell (Mrs)” … address in Morbay – the posh end,’ she added.

Heffernan placed it on the desk in front of him and stared at it for a while before speaking. ‘Probably a crank,’ he murmured

as he pushed it to one side.

Rachel looked sceptical. ‘Cranks don’t usually provide their name and address.’

‘I suppose we’ll have to follow it up … send a couple of uniforms round. No hurry.’

‘How much do you know about the case, sir?’

Heffernan sat forward and thought for a few moments. ‘It must have been about twelve years ago … I was a DS in Morbay at the

time so I wasn’t involved. A vicar was murdered in the course of a burglary and Chris Hobson was arrested. Witnesses had seen

him in the village around the time of the murder and the stolen goods were found in his flat. It was an open-and-shut case

as far as I can remember.’ He sat back and gave a long sigh. ‘No use rocking the boat just because someone wants to start

a “Chris Hobson is innocent” campaign. If he was that innocent why didn’t this Mrs Powell come forward before? Why wait all

this time? Forget it, eh.’

Rachel nodded. Perhaps the boss was right: sleeping murderers should be allowed to slumber on undisturbed … especially if

the only justification for waking them was some vague letter.