The Phoenix Generation (12 page)

Read The Phoenix Generation Online

Authors: Henry Williamson

“Well, Mother, it’s not exactly in my line. You see, I have to shut my mind to some things, in order to think about the trout book.”

“Yes, of course, naturally. But I thought this might interest you particularly, after our walk to the Coppice, all of us together, when we were here for the christening of Billy and Peter. Do you

remember? Hilary, Irene, Dora, Uncle John, your friend Piers—Oh, I did so enjoy that visit. You told us about the prices of coppice wood—well, this is about another coppice, Father said, because the Hanger Copse was chestnut and hazel, this was for oak, grown for tanning leather as well as for firing. It was written in seventeen eighty-five, in the Steward’s book.”

Dead—dead—dead stuff—the blind trout slowly dying of—inanition——

Upon a Statute Acre of Coppice Oak Wood of seventeen years Growth there should grow two tons of Bark and twenty two cords of Wood.

Three Wood Acres make very near Five Statute acres.

One Good Load of Wood in a kiln will burn Fifteen Yard of Lime.

16½ ft. to a Perch to a Statute Acre.

21 ft. to a Wood Acre.

A Cord of Wood is 8 ft. 4 inches long, 4 ft. 6 inches high, 2 ft. 6 inches in length of Billet.

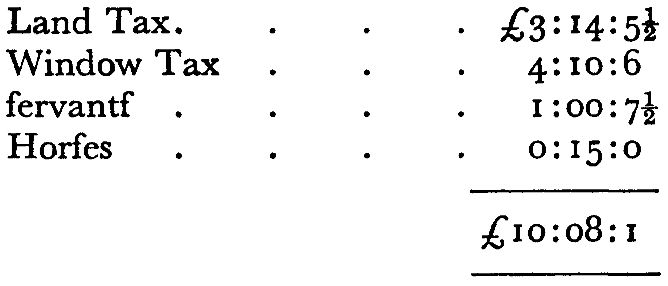

Half a year’s land tax and window money at 4/- comes to

£

8:04:11½ Tax in All thus—

“I make the total ten pounds and sevenpence.”

“Here’s a list of the names of the men employed, Phillip. There were forty in those days. Just think of it.”

“I don’t want to think about it, Mother. I want to think of the blind trout. Why don’t

you

write a book about all this?”

“I would if I had your gift, my son.”

“As I told you when you first came down here, Mother, my talent is buried, with most of my generation. No, that’s

sentimental

. But as a fact it is not possible to give all my imagination to what I want to write just now. Perhaps I’ll be able to write it in my field at Malandine.”

It was an idea. That was the place. A writer should have a secret pied-à-terre—

As he was leaving she dared to ask about his secretary. “Has Miss Ancroft finished her secretarial duties, Phillip?”

“Yes, Mother. Felicity left because she wants to be on her own—to write. And meanwhile, keep herself by typing. She’s going to advertise for work in

The

Writer.”

Dearest Phillip,

I’m awfully sorry, darling, but however hard I try, I

cannot

feel myself to be a ruined girl—no, I am not the ruin

able

sort—though perhaps ruin

ous.

And as no-one else feels that—three rousing cheers. All the same, I seem to sense that you are not altogether happy. I wish I could determine once and for all if you would be better away from your home—and act upon it. Why should you, as you write from your field in Malandine, be ‘almost afraid’ to go back to your lovely valley? Darling, you must not let your heart wither away. It must not be wasted by a sort of slow petrifaction, but allowed to flow out easily and without strain.

I have rented a room here from mother, and am typing a novel—as I told you—I have advertised in

The

Writer.

And am also doing my own work. When I see you again I shall be a new girl for you, without any more silly mistakes.

Always yours,

Felicity.

If only he could settle to a clear prospect of what to write. If only life were simple, as in those years after the war, in the cottage at Malandine. Now to think. The first rough draft of water-scenes was done; now to determine the dramatic theme. It was fishing weather in the West Country with hatches of fly every noon, and trout on the move. He stood beside the river, watching the rises of trout, and the insect traffic upon the water; making notes of the times of flies hatching, and identifying them with a book with coloured plates by Halford. He made notes on the buoyancy and grace of cloud formations high in the dome of the sky which brought lightness of heart to man, bird, and fish—the nymphs swimming to the surface of the stream, to arise tremulously to the shelter of willow and alder, there to cast their pellicles, those diaphanous coverings of wing and body, to await the nuptial flight into the sky of late afternoon. He came to know the regular stances of the trout, day after day, when they were feeding just under the surface.

One morning he noticed a fish, over three pounds in weight, darker than the others, a lean fish the colour of which was almost black. As the days went on he saw that it was always in the same place, in relation to the rise, but never seemed to take any flies. He used a telescope to watch it; and seeing smaller trout, again

and again, rising to flies just under the surface, observed that this fish never appeared to feed. It stayed in one place, using small slow movements of fin and tail and evenly opening its mouth to breath—but nothing more. Could it be blind?

How could a blind fish feed? Had it a sense of smell, like an eel? Was it hovering in its stance by day, at the times of hatching, only out of habit, having nothing else to do with its life? Did it feed on minnows in the shallows, by sensing the nearness of the little fish by the nerves along the lateral nerve-lines of its body?

Now for a theme, to relate observation to a story with its own life. Take several fish and relate their lives as individual fish, with the blind, black, and aged trout symbol of the obsolescence,

leading

to its death. A symbol, hidden and never revealed directly, of dying Europe? No politics. Keep to the blind trout. Relate its condition to the pollution of so many rivers due to the

industrialisation

and the squalor of the machine age. Be neither romantic nor sentimental: a fish is a fish is a fish, as Gertrude Stein said of a rose. It existed; no more than that. The problem to solve was, How did this blind trout exist? And was it black because the sense of protective colouration was put in action by the optic nerve? A blind trout living through eternal night? Pollution? The Flumen was one of the purest rivers in the West Country …

He hurried home, packed up his note-books, addressed and posted them to Felicity. Would she type them at once and give any ideas, or reactions from the notes, about how the story might go? He would pay her for this work at the rate of fifteen shillings a day.

Darling,

Of course I will give you priority for the trout and river notes and impressions which arrived just now, and tell you exactly how they strike me. I am sorry you have to chip every word from your breast-bone. What you tell me about the blind trout is exciting. You are wonderful in your scenes of darkness, cold starlight, and the first electric pallor of dawn arising before the ‘rosy fingers’ of the Greeks.

Now I don’t want one speck of Ancroft pollen—mère ou fille—for I can hardly describe myself a

jeune

fille

—to touch the opening flower, but the fact is, I am in a quandary. I must leave home at once, but it is difficult, almost impossible, for me to begin looking for a cottage because I have no money of my own. There is ‘alternative

accommodation

’, as they say, but it involves a tentative acceptance of an offer of marriage which I do not want to consider, even, feeling as I do. Also it would be rather a shock to my mother. I am sorry not to be

more explicit, perhaps I should not have mentioned it, anyway it is ‘out’.

Do you think you could let me have an advance of, say,

£

5 for the typing, so that I could look at some cottages offered in

The

Lady

? They are usually very cheap ones advertised in that magazine. I would not ask this were I not desperate, for I know you must not stop writing when ‘the honey flow is on’. Also you have so many mouths to feed.

Could you come up for a couple of days, and take me in your lovely Silver Eagle to look at various cottages? As I said, I am most loath to interrupt your work, but a cottage of my own would enable me to feel free and unencumbered in mind, so that I can give all of it to help you in your work. I myself am in my usual health and feel buoyant and optimistic.

Later.

Perhaps it would save you a journey to London if, in the course of your wandering, you come across any cottage that is to be let, the humbler the better. Will you let me know?

He would go to London on the morrow. He must take her a basket of trout. He was tired: the idea of putting on waders, oversocks, and nailed canvas boots was too much. The sun was going down behind the hill. How lonely, bereft, was the earth without sunlight. Even under morning and afternoon light there was a vacancy in the valley: sameness of walks by the river: the same trout to be caught on barbless hooks and put back, to

disappear

for a day or two and then they were back at their stances, before and below the old blind trout slowly waving its life away.

It was no good fishing now that a mist was beginning to lie upon the meadows. He couldn’t see to tie the fly properly. Was his eyesight failing? Could it be due to that temporary blindness by mustard gas in his youth? The knot was wrong anyway, he could not see to bend the gut round the eye of the shank. It

became

a grannie knot. He cast badly. The fly

struck

the water, he

snatched

it back—he was all jangle, disintegrated, no harmony between eye, arm, and heart. He tried again. The fly was caught in an alder branch. He snatched it back and the cast snapped. He was always meaning to cut back the branches, and here it was June, he hadn’t really fished properly that season, no time to do anything. He waded across but could not see where the fly was caught. His legs felt chilled and heavy. He got out of the water and walked to the bridge, to look down into the pool from his usual place in the centre of the parapet.

The sinking sun was lengthening oak and alder shadows. Red spinners of the midday hatch of olive dun were now rising and falling regularly over the gliding copper-plated surface of the river.

He stood below the bend, with no desire to fish, his mind empty save for an impersonal feeling of sadness which he knew came from nervous exhaustion. For some time now the river had been

him.

He had known, sensed, and

lived

in every gravelly stone, bubble, grain of sand: yet that part of his life, because it had remained

unwritten

, was as ephemeral as the air-life of one of the spinners, those creatures, frail and delicate, their mouths sealed against the need of food or water, living only on air during their brief winged life between the rise and setting of their one day’s sun.

Love

is

a

full

growing

and

constant

light:

But

his

first

minute

after

noon

is

night.

The water was low and clear. Cattle in the morning and

afternoon

heats had been cooling themselves under the shade of the alders, but the slight cloudiness of loam in the gravel had settled, so that, peering down into the water at noon, he had seen every stone and speck of gravel, every tiny spotted samlet of the late winter’s hatching.

During the early part of the year the water had been high, the spring-heads in full gush, salmon coming in from the Channel had been able to run up higher than was usual at the beginning of the season.

As the level dropped in April, the salmon sought the deepest water they could find, in the pools and by the hovers of the banks.

And as the springs lessened their upwelling in May, the salmon were forced to spend most of the daylight under the muddy roots of the waterside alders, waiting for twilight and cooler water from the great reservoirs of the chalk downs and safety from the glare of day.

There was a solitary salmon lodged under a clump of roots a few yards below where Phillip was standing at the bend. The water there was about two feet deep, and the salmon was trapped.

He had been watching that fish for more than two months. Its life was one of solitary confinement. When it had first appeared, in April, it had been a bluish-silver, and very lively. Now its scales were a pinkish brown and the fish was dejected.

Its tail could usually be seen sticking out of the roots about eleven in the morning, before the shadow of a branch hid it.

Sometimes when he had gone to the bridge about noon he had

seen the fish sidle out of the roots, turn slowly into the wimpling current, to idle there like a great trout for a few moments, its back-fin out of water, and then to gather way while it prepared for a leap—a great splash, and it had fallen back, while the narrow river rocked and rippled with the impact. After remaining in midstream for a minute or so the fish would drift backwards to its hiding place, slowly, almost wearily, and push itself under the roots again.

Now, on this evening in late June, Phillip was standing beside the run, a small seven-foot rod of split cane weighing two ounces in his right hand. He was about to drop lightly an imitation of a red spinner—the olive dun which had shed the pale green pellicle or sheath of morning for its one dance of love-and-death—upon the wimpled surface when something made him pause and remain quite still.