The Perfect Heresy (8 page)

Read The Perfect Heresy Online

Authors: Stephen O'Shea

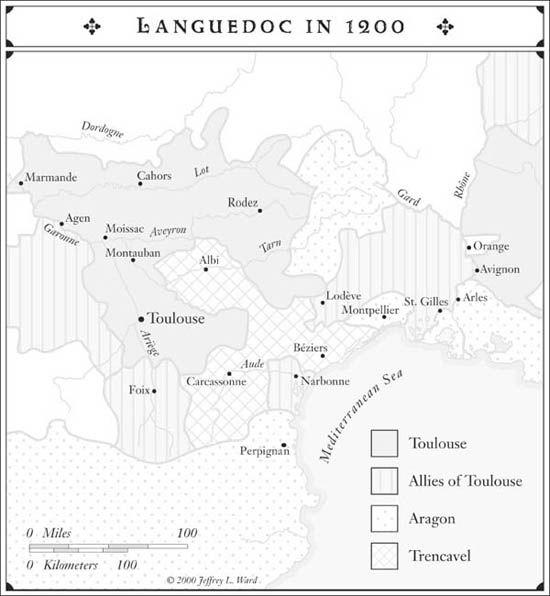

The years of absentee landlordship by the Saint Gilles would cost them dearly. As the twelfth century progressed, the south saw repeated disputes over jurisdiction as the rising clans of the north pressed claims to areas under the weak control of the Saint Gilles. Strategic marriages forestalled any great armed conflict—although Raymond’s father had to undertake a series of minor defensive fights—so that by 1200 the Saint Gilles held territory in Provence as vassals of the Holy Roman emperor, land in the Toulousain from the king of France, and property in Gascony from the king of England. The king of Aragon had won control over much of the Mediterranean coast of Languedoc, including the important town of Montpellier. Given the rivalry between these overlords, the threat of war hung heavily over Languedoc. The balancing act required of Raymond VI was extremely delicate, especially as he, unlike northern barons and monarchs, did not own huge estates outright on which to rely for revenue or armed knights.

Raymond fared little better as liege lord of the greater noble families of the region. In the rugged foothills of the Pyrenees, mulish independence was the rule, not the exception. The count of Foix, the man whose sister and wife became Perfect and who won the heart of the she-wolf Loba, exemplified the type of miscreant whose excesses Raymond was expected to curb. Whenever Raymond Roger of Foix murdered a priest or besieged a castle, as he sometimes did, Raymond of Toulouse was powerless to punish him, even had he been so inclined. The other mountain lords were similarly independent.

The prickliest thorn in Raymond’s side came from the Trencavel

family. They sat squarely in the middle of Languedoc, firmly ensconced behind the battlements of Carcassonne. Their vast holdings around the city, stretching as far as Béziers, sundered the Saint Gilles lands in two. To ensure their independence from Toulouse, the Trencavels had made themselves vassals—and thus protégés—of Aragon in 1150. Raymond, showing his usual preference for the bedroom over the battlefield, tried to neutralize the threat from Carcassonne by taking a Trencavel trophy wife, Beatrice of Béziers. Instead of founding a new dynasty, the couple eventually had their marriage annulled, and Beatrice became a chaste Cathar holy woman. It is unknown whether she went willingly or was shoved aside by Raymond, whose infatuation with the daughter of the king of Cyprus led to his third marriage. The result was that the patchwork of Trencavel and Saint Gilles loyalties remained as motley as ever.

The Church made the situation in Languedoc even more complex. Bernard of Clairvaux’s Cistercian monastic movement—the reforming wing of the Benedictine family—had spread from its founding house in Cîteaux, Burgundy, to the south, attracting the talents of such men as Fulk of Marseilles, who would become the bishop of Toulouse. Its zealot monk-farmers, still in that period of grace when successful monasticism did not mean excessive waistlines, amassed thousands of acres of property through a combination of hard work and bequests of land from people hedging their bets on the hereafter. Visitors to present-day France, marveling at the picturesque ubiquity of villages no matter how steep the slope, wet the marsh, or barren the moor, are

often admiring of the handiwork of the monks. They tamed the last wildernesses, enticed peasant pioneers into newly founded settlements, and became a tonsured gentry managing enormous estates. Given the absence of legitimate offspring among monks, these estates would not be subdivided in later generations.

Such wealth did not go unnoticed. First in line for a share of the riches were the Cistercians’ fellow churchmen, the secular clergy—that is, priests living in lay society as opposed to the regular clergy, monks following some prescribed communal rule. Among Languedoc’s secular clergy, there were breathtaking differences in levels of piety, liturgical literacy, and financial solvency. Bishops feuded with abbots over money, sometimes leaving parish churches vacant for years, their taxes and tolls the subject of acrimonious dispute. The office of bishop was a position very much of this world—as the Cathars never failed to deplore.

The strife between the monastic regular clergy and the secular clergy paled in comparison to the woes inflicted on them by the Languedoc laity. Attacking the property and persons of priests was something of a national pastime. The “Peace of God” movements, essentially oaths by which rambunctious nobles swore not to despoil defenseless clerics, had been started as early as the tenth century. In Languedoc, with its chronic lack of central authority, there was no force powerful enough to ensure that these oaths would be upheld. The glue of medieval society was coming unstuck. Hard-strapped counts, viscounts, and members of the petty nobility seldom came to the aid of embattled bishops—who, in any event, were rarely paragons of virtue. Tithes were routinely diverted to the coffers of secular grandees or simply not paid at all. In 1178, the Trencavels had thrown the bishop of Albi in prison; the following year, they

added insult to injury by extorting a whopping 30,000 sols from the monastery of St.-Pons-de-Thomières.

*

Count Raymond of Toulouse made it something of a hobby to harass the abbots of the monastery near his ancestral seat of St. Gilles, a town in the Rhône delta.

Often the conflicts verged on the macabre. In 1197, the Trencavels contested the election of a new abbot in the highland monastery of Alet. Their emissary, Bertrand of Saissac, a nobleman with several Cathar Perfect in his family, came up with a novel solution to the dispute. He dug up the body of the former abbot, propped it upright in a chair, then called upon the horrified monks to listen carefully to the corpse’s wishes. Not surprisingly, given such ghoulish encouragement, a friend of the Trencavels easily carried a new election. To make the proceedings legal, the consent of the Catholic hierarchy was needed, so Bertrand turned to the archbishop of Narbonne, the preeminent churchman of Languedoc. He was also its preeminent grifter. Innocent III would write of the Narbonne clergy in exasperation: “Blind men, dumb dogs who can no longer bark … men who will do anything for money … zealous in avarice, lovers of gifts, seekers of rewards… . The chief cause of all these evils is the archbishop of Narbonne, whose god is money, whose heart is in his treasury, who is concerned only with gold.” The Trencavel request for confirmation of the new abbot’s election came augmented by a handsome payoff, and approval was promptly given. A Catholic chronicler noted somberly that many people in Languedoc, when refusing to do a particularly unpleasant task, reflexively used the expression “I’d rather be a priest.”

Although such anticlericalism existed elsewhere, Languedoc

’s quarrels were endemic, not episodic, and came to be played out in a society that did not have just nobility and clergy competing for prizes at the expense of the peasantry. For, like Lombardy in northern Italy and Flanders by the English Channel, Languedoc of the year 1200 had become a landscape of towns, full of obstreperous burghers elbowing their way into what was once thought a divinely ordained procession of priest, knight, and serf.

Stadtluft macht frei

(City air makes men free) would run the later German byword about medieval towns, and Languedoc’s precocious experience proved the axiom fully. The main centers—Montpellier, Béziers, Narbonne, Albi, Carcassonne, Toulouse—teemed with energy, most of them recovering the vigor they had known a millennium earlier under the Romans.

Toulouse, the most important of the lot, was self-governing, having purchased its freedoms from Raymond’s father and elected consuls, called

capitouls

, to legislate in a new town hall built in 1189. In any city where a consular system took root, civic truculence became automatic. In 1167, the year of the Cathar meeting at St. Félix, the merchants of Béziers had even gone so far as to murder their Trencavel viscount. The capitouls of Toulouse, perhaps reflecting the diplomacy and disposition of their count, preferred to legislate reasonably about their pursuit of wealth and pleasure. An observer noted that in the city, a married person could not, by a law of the capitouls, be arrested “for reason of adultery, fornication or coitus in any store or house he or she rented, owned or maintained as a residence.” Clearly, Languedoc’s mix of troubadour and trader culture was cocking a snook at the Church.

The towns also began tolerating ideas and people usually kept outside the confines of the feudal Christian commonwealth.

Groups at the margin of society—and not just heretics—began testing the waters of the mainstream. Languedoc’s numerous Jews, who had lived in the region since the time of the Romans, were among the prime beneficiaries of the culture of clemency that arose out of the crossfire of southern noble, cleric, and townsman. An Easter tradition called “strike the Jew,” whereby members of the Toulouse Jewish community would be batted around a public square by Christians, was ended in the middle of the twelfth century, after hefty payments had been made to count and capitouls. The clergy protested, but the ban held. The Church, which had evolved a policy of clearly delineated ostracism of the Jews, howled even louder when non-Christians were allowed to own property and, in some instances, hold office. In Béziers in 1203, the chief magistrate in the Trencavel lord’s absence—or

bayle

—was a Jew named Simon. In Narbonne, which supported a Talmudic school and several synagogues, some Jewish merchants possessed vineyards in the surrounding countryside and employed Christian peasants to work the land, an open flouting of the Church’s prohibition on Jews having any kind of authority over Christians. Whereas these changes were usually effected through the greasing of palms or the paying of steep taxes, they nonetheless signaled the dawning of a freer, or at least more freewheeling, society.

From the perspective of a newly invigorated Rome, all of this took on the appearance of an infernal downward spiral, a slippery slope of moral and spiritual degeneracy. While hardly a multicultural Camelot, as sometimes suggested by its twentieth-century boosters, medieval Languedoc was exceptional enough to be viewed as objectionable. Innocent III would write frequently to Count Raymond and implore the scion of crusaders to act. One letter seethes, “So think, stupid man, think!”; another

calls him a “creature both pestilent and insane.” It is not clear, however, whether Raymond could act, given the fetters on his power, the autonomy of the towns, and the subversive spiritual tolerance that now existed between Languedoc’s Catholics, Cathars, and Jews.

As it turned out, Raymond did nothing. The count of Toulouse would not persecute his own people. Innocent and his advisers, at a loss without a noble ally in Languedoc to suppress dissent, had to work a revolution of their own. As the new century dawned, the men of the Church set out to convince Raymond’s people of the error of their ways. They met the heretics face-to-face.

The Conversation

T

HE CATHARS AND THE CATHOLICS

argued. On points of doctrine and Latin, on the role of the Church and the devil, on the nature and meaning of humanity’s existence, on the beginning and the end of the cosmos. In the first years of the 1200s, Languedoc became a land of loud disputation, a medieval Chautauqua held by competing speakers with souls to save and demons to vanquish. The churchmen sought out the heretics and challenged them to debate. Local lords guaranteed safe-conduct for the participants and made their great halls and castle courtyards, ordinarily the haunt of troubadours and jongleurs, available to the robed holy men. Priest and Perfect squared off in blazing sunshine and guttering torchlight as the laity came in from the fields and out of the taverns to listen and to learn.