The Passport in America: The History of a Document (36 page)

Read The Passport in America: The History of a Document Online

Authors: Craig Robertson

Tags: #Law, #Emigration & Immigration, #Legal History

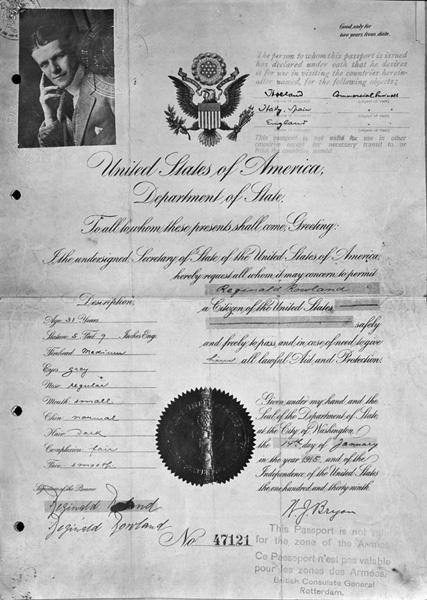

U.S. officials became even more concerned when, in the middle of 1915, it became apparent that the German government was producing its own fake U.S. passports, no longer merely seeking to acquire legally issued passports. The first and most celebrated case involved George Breeckow, who used a fake U.S. passport to enter England, copied from a legitimate passport issued to Reginald Rowland, who had had his passport temporarily taken for inspection by German officials when he had checked into a Berlin hotel several months earlier (

figure 10.1

). Despite carrying a copy of this passport and arriving as Reginald Rowland, Breeckow was arrested on suspicion of espionage soon after his arrival in England. The discovery of his fake passport received substantial newspaper coverage in the United States because, in the words of one newspaper, it provided the first evidence of “the abuse by one nation of another nation’s sacred seal and of the deliberate forgery by agents of one nation of the signature of the Secretary of State of another and friendly power. Officials here are amazed that it has been possible to procure such definite proof.”

52

According to the report on Breeckow’s passport forwarded to the State Department by the U.S. Ambassador in London, although the passport was a good enough copy to “deceive a casual observer,” a “chemical analysis and comparison” revealed “unequivocally” that the passport was a fraud.

53

Thus the war saw the passport enter the world of modernization and rationalization, both in its production and, gradually, in the determination of its authenticity—the passport could be as much the object of an “objective” gaze as the person who carried it. The report on Breeckow’s passport included the results of tests on fiber, dyestuff, and “the Biuret test” on paper type; close examination of the eagle at the top of the passport also revealed discrepancies in the wings, tail feathers, and the background of the thirteen stars.

54

Final confirmation that the passport was a fake came when State Department agents located Reginald Rowland, who had “preserved his passport in a beautiful way.” As was common among travelers of the period, he had framed it as a souvenir of his European vacation.

55

Breeckow was executed by firing squad in England on October 26, 1915. Prior to his execution, he told a U.S. consul “he had no

Figure 10.1. George Breeckow’s fake U.S. passport, 1915 (National Archives).

complaint to make except that he felt that as he had not succeeded in transmitting any information to Germany, the punishment was rather severe.”

56

While fraud and forgery showed potential faults in the documents and procedures used to implement passport control, officials along the Mexican border viewed the entire system of passport control as flawed and illogical. Although verifying citizenship at the Mexican border was invoked as a reason for the 1918 Passport Control Act, officials on the ground saw little value in the passport owing to the large number of daily border crossers and the vast stretch of land under official watch. Their experiences made clear that the top priority for passport control and wartime border security was seaports (particularly New York, the sole port for wartime Atlantic crossings after 1916), where, to state the obvious, people arrived and left the country in ships, “closed containers” that people could not easily leave or enter until arrival at a specific location.

57

In contrast, along land borders people could simply enter the United States over the open stretches of land between the major cities. An initial attempt to prevent this came in the form of a small group of inspectors hired to patrol the border, intended to make inspection more mobile. Known as “passport employees,” these were mounted inspectors who policed the land border toward the end of World War I. According to one former inspector, these “fairly rough characters,” hired from “local ranchers and cowhands,” rode in groups of three or four. They “proved themselves of considerable value particularly deterring cattle and horse thieves from running livestock across the border into Mexico.”

58

Passport control was further hampered by the limited number of officials assigned to designated entry points. It was estimated that if the document requirements were to be rigorously enforced in any useful way, an additional sixteen inspectors and two stenographers would be required to keep record of the approximately four thousand Mexicans who crossed the border daily through the towns of Nogales, Naco, and Douglas; this estimate did not include the work of inspecting the documents of other foreigners.

59

As a result, inspectors often felt that personal knowledge should trump the time-consuming effort of verifying identity through documents; most of the Mexicans who crossed the border did so on a daily basis as part of their “commute” to work. While one report noted “there is very little of the looseness of personal recognition”

60

at El Paso, pressure there and from local chambers of commerce not to impede

the flow of laborers created a less-than-rigorous documentary regime along the Mexican border. Officials in Washington, D.C., continued to be frustrated even in situations in which documents replaced personal recognition. U.S. and Mexican border officials regularly accepted documents other than the passport, including passport applications and certificates issued by local authorities.

61

Therefore, while the commissioner general of immigration praised the effectiveness of passport control at New York in the 1918 Immigration Bureau annual report, in that same report Frank Berkshire, who had been in charge of immigration inspectors along much of the Mexican border since 1907, complained that enemy agents simply avoided official ports of entry along the land border; “Therefore, the passport regulations as now enforced discommode thousands of loyal, or in any event, not unfriendly persons whose legitimate business or innocent pleasures naturally take them through the regular channels, while the frontier elsewhere is inadequately guarded. This is wholly wrong, illogical, wasteful and dangerous.”

62

His frustration grew when he saw a role for the passport in targeting the actions of disloyal citizens who sought to cross the border for what he considered was not innocent pleasure. After the introduction of Prohibition, Berkshire sought permission to deny passports and other necessary documents to citizens who wanted to travel to Tijuana to drink. Despite endorsements of this initiative from local civic officials and religious groups, the State Department continually refused to allow Berkshire to act as a “censor of morals,” and instructed that passports and border permits be issued to the so-called “thirsty tourists” who crossed into Mexico to drink alcohol.

63

Berkshire’s argument, that the focus of passport control on “loyal” and “not unfriendly persons” created a border system which was “illogical, wasteful and dangerous,” inadvertently pointed to a strength of d ocumentarybased systems of border management. In this sense, the passport was not simply a technology of exclusion; it introduced citizens to a developing documentary regime of verification. The passport and visa applications and their potential use as records of the movement of citizens and aliens are examples of a “modern” form of government based on more complete knowledge of the population and society. This could be used not only in the logic of wartime surveillance, but also as the basis of statistics that could inform practices of governing. The war created a need for information, and not necessarily for any known purpose; rather, it gave rise to the belief that the government simply had to know and be able to remember all possible knowledge about its population and society. Prior to the war the limited collection and analysis of information meant that the government did not know with any accuracy

facts that became critical to mobilization such as the country’s net financial reserves, total industrial production, and the potential combined transportation capability.

64

In reaction to the outbreak of war in Europe, mobilization saw the importation of the management logic that had developed in major industries into parts of the federal government.

65

After President Wilson sanctioned the Civilian Advisory Commission for the collection of information, centralized agencies concerned with specific economic sectors were created, such as for food and fuel, that prioritized systematic gathering of data and centralized administration.

66

While it is not clear if any government official explicitly articulated the passport to this project, the war showed how identification documents could manage difference, not simply through the documentation of identification categories, but more astutely through the knowledge of the individuals who comprised these categories, and the production of more precise identification categories, a role that immigration and passport policies in the 1920s would increasingly make apparent.

Beyond attempts to document the identity of aliens and citizens entering and leaving the country, the federal government instituted surveillance practices to monitor what it considered suspect populations within the country in the context of this increasingly pervasive project to collect information. These early attempts to gather knowledge on specific individuals within the United States illustrated the potential of a systematic administrative structure for the acquisition of information about people rather than more benign objects such as the growth of corn or the production of automobiles. Beginning with German spies and sympathizers, the initial attempts at domestic surveillance moved to labor and left-wing political organizations.

67

The initial targeting of Germans took the form of informal surveillance within unofficial attempts to limit German presence in the United States. Preexisting Progressive Era concerns about immigration evolved into efforts to target German music and books, and more specific instances of a loosely conceived sense of German cultural identity: the hamburger became the liberty sandwich, sauerkraut was renamed liberty cabbage, and, somewhat more illogically, German measles became liberty measles.

68

However, following the entry of the United States into the war, a series of laws formalized such prejudice through the legal surveillance of citizens of German descent: the Espionage Act of June 15, 1917; Trading with the Enemy Act of October 6, 1917; and the Sedition Act of May 16, 1918. Presidential proclamations were also issued that labeled all German males aged fourteen and over “enemy aliens” (April 6, 1917) and required the registration of all German males (November 16, 1917) and

then German females (April 19, 1918). Non-German U.S. citizens were not exempt from state-sponsored attempts at surveillance. Although not necessarily thought of as such the Selective Service Act functioned to register, and thus collect information about, citizens eligible for military service. By the end of the war, it resulted in more than 24 million male citizens aged eighteen to forty-five being registered for the draft through the establishment of local draft boards; about 12% of them would eventually serve.

69

How effective was the employment of the powers of surveillance in these acts and regulations? The responsibility initially fell on a woefully under-staffed federal police structure centered on the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Investigation. Created in 1908, it had gained a semblance of responsibility following the passage of the Mann Act in 1910, in which Congress utilized the federal government’s right to control interstate commerce to make it a federal offense to transport a woman across interstate lines for immoral purposes. But in 1914 the Bureau of Investigation still only had one hundred agents; by the end of the war it had four hundred agents operating among a population of 100 million. Under the leadership of Bruce Bielaski (whose sister Ruth Shipley would later run the Passport Division for almost three decades, from the late 1920s to the early 1950s), the bureau attempted to both consolidate and centralize information on suspicious individuals. It also employed agents, largely recruited from the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, to investigate both suspected German spies and radical agitators. It was further assisted by the American Patriotic League (APL), which at the end of the war counted 250,000 members. In his 1918 report the attorney general called the APL “invaluable to the government as an auxiliary force”; in his history of the United States and World War I David Kennedy labels them “a rambunctious, unruly

posse comitatus

on an unprecedented national scale.”

70

The main target of APL chapters became citizens who did not register with local draft boards; large-scale raids tended to discover small numbers of “slackers,” identified by their failure to produce an identification card that showed they had registered for the draft. The Selective Service Act was in fact implemented through volunteer groups, befitting the purportedly voluntary nature of the draft, but more practically, an acknowledgment that the federal government was not the massive bureaucracy such an act required. Volunteers staffed draft boards in smaller towns, with President Wilson appointing prominent local citizens to boards in larger cities.

71

In contrast, the registration of Germans made use of existing state apparatus. Germans had to report to a local police station or post office to fill out

detailed forms, supply several photographs, and give fingerprints. They were then issued an identification card with their name, address, photograph, and thumbprint, which they were required to carry at all times. Through the information collected in the registration process, officials believed they could identify possibly hostile aliens and, if not deport or incarcerate them, at least keep them away from vital resources.

72

By the end of the war, surveillance practices had become part of the twentieth-century U.S. state in the form of the Bureau of Investigation and the enforcement of these acts and regulations, along with their accompanying procedures such as internment, denaturalization, and deportation. This new form of state and its relationship to citizens and aliens also included immigration offices and passport agencies.

73