The Paleo Diet for Athletes (29 page)

Read The Paleo Diet for Athletes Online

Authors: Loren Cordain,Joe Friel

MACRONUTRIENT BALANCE

We’ve already mentioned that the fat content in Paleolithic diets (28 to 57 percent total calories) was quite a bit higher than values (30 percent or less) recommended by the American Heart Association and the

USDA’s MyPlate. We suggest consuming between 30 and 40 percent of your Stage V energy as fat. How about carbohydrate? In hunter-gatherer diets, carbohydrate normally ranged from 22 to 40 percent of total daily energy. Because of your special need as an athlete to restore muscle glycogen on a daily basis, you should boost these values a bit higher. We suggest that Stage V carbohydrate intake should typically range from 35 to 45 percent of calories. As you personalize the Paleo Diet for Athletes to your specific training schedule and body needs, you will be able to fine-tune your daily intake of carbohydrate, fat, and protein.

NUTRITIONAL ADEQUACY

Regardless of your final ratio of protein to fat to carbohydrate, you will be eating an enormously enriched and nutrient-dense diet, compared with what you were probably eating before. We’ve partially addressed this concept in

Chapter 1

, where we compared the Paleo Diet for Athletes with the recommended USDA Food Pyramid/MyPlate diet, and also in

Table 9.5

. An even better way to appreciate how much more nutritious your diet will become when you adopt the Paleo Diet for Athletes is by looking at what the average American eats.

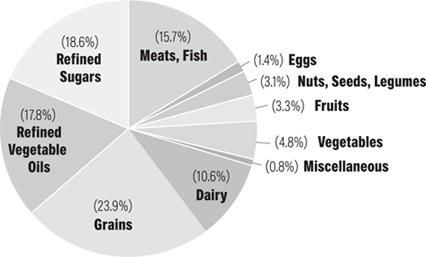

Figure 9.2

shows the breakdown by food group in the typical US diet. Notice that grains are the highest contributor to total calories (23.9 percent), followed by refined sugars (18.6 percent) and refined vegetable oils (17.8 percent). When you add in dairy products (10.6 percent of total energy) to grains, refined sugars, and refined oils, the total is 70.9 percent of daily calories. None of these foods would have been on the menu for our Paleolithic ancestors, as fully discussed in

Chapter 8

.

Refined sugars are devoid of any vitamins or minerals, and except for vitamins E and K, refined vegetable oils are in the same boat. Think of it: More than a third of your daily calories come from foods that lack virtually any vitamins and minerals. When you add in the nutrient lightweights we call cereals and dairy products (check out

Table 9.5

,

you can see just how bad the modern diet really is. The staple foods (grains, dairy, refined sugars, and oils) introduced during the agricultural and industrial revolutions have displaced more healthful and nutrient-dense lean meats, seafood, and fresh fruits and vegetables. Once you begin to get these delicious foods back into your diet, not only will your vitamin, mineral, and phytochemical intake improve, but so will your performance.

FIGURE 9.2

CHAPTER 10

T

HE

P

ALEOLITHIC

A

THLETE:

T

HE

O

RIGINAL

C

ROSS

-T

RAINER

Ten thousand years sounds like a long, long time ago. But if you think about it in terms of how long the human genus (

Homo

) has existed (2.3 million years), 10,000 years is a mere blink of the eye on an evolutionary time scale. Somewhere in the Middle East about 10,000 years ago, a tiny band of people threw in the towel and abandoned their hunter-gatherer lifestyle. These early renegades became the very first farmers. They forsook a mode of life that had sustained each and every individual within the human genus for the previous 77,000 generations. In contrast, only a paltry 333 human generations have come and gone since the first seeds of agriculture were sown. What started off as a renegade way of making a living became a revolution that would guarantee the complete and absolute eradication of every remaining hunter-gatherer on the planet. At the dawn of the 21st century, we are at the bitter end. Except for perhaps a half dozen uncontacted tribes in South America and a few others on the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal, pure hunter-gatherers have vanished from the face of the earth.

So what difference does that make? Why should 21st-century endurance athletes care one iota about whether or not there are any hunter-gatherers left? Because once these people are gone, we will no longer be able to examine their lifestyle for invaluable clues to the exercise and dietary patterns that are built into our genes. When I was a track athlete in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, runners rarely or never lifted weights, and no runners worth their Adidas or Puma flats would even think about swimming. Fast-forward 40 years. What progressive coach now doesn’t know the value of cross-training? Those benefits might have been figured out much earlier had we only taken notice of clues from our hunter-gatherer ancestors.

Very few modern people have ever experienced what it is like to “run with the hunt.” One of the notable exceptions is Kim Hill, PhD, an anthropologist at Arizona State University who has spent the last 30 years living with and studying the Ache hunter-gatherers of Paraguay and the Hiwi foragers of southwestern Venezuela. His description of these amazing hunts represents a rare glimpse into the activity patterns that would have been required of us all, were it not for the agricultural revolution.

I have only spent a long time hunting with two groups, the Ache and the Hiwi. They were very different. The Ache hunted every day of the year if it didn’t rain. Recent GPS data I collected with them suggests that about 10 km per day is probably closer to their average distance covered during search. They might cover another 1-2 km per day in very rapid pursuit. Sometimes pursuits can be extremely strenuous and last more than an hour. Ache hunters often take an easy day after any particularly difficult day, and rainfall forces them to take a day or two a week with only an hour or two of exercise. Basically they do moderate days most of the time, and sometimes really hard days usually followed by a very easy day. The difficulty of the terrain is really what killed me (ducking under low branches and vines about once every 20 seconds all day long, and climbing over fallen trees, moving through tangled thorns, etc.). I was often drenched in sweat within an hour of leaving camp, and usually didn’t return for 7-9 hours with not more than 30 minutes rest during the day. The Ache seemed to have an easier time because they “walk better” in the forest than me (meaning the vines and branches don’t bother them as much). The really hard days when they literally ran me into the ground were long distance pursuits of peccary herds when the Ache hunters move at a fast trot through thick forest for about 2 hours before they catch up with the herd. None of our other grad students could ever keep up with these hunts, and I only kept up because I was in very good shape back in the 1980s when I did this.

The Hiwi on the other hand only hunted about 2-3 days a week and often told me they wouldn’t go out on a particular day because they were “tired.” They would stay home and work on tools, etc. Their travel was not as strenuous as among the Ache (they often canoed to the hunt site), and their pursuits were usually shorter. But the Hiwi sometimes did amazing long distance walks that would have really hurt the Ache. They would walk to visit another village maybe 80-100 km away and then stay for only an hour or two before returning. This often included walking all night long as well as during the day. When I hunted with Machiguenga, Yora, Yanomamo Indians in the 1980s, my focal man days were much much easier than with the Ache. And virtually all these groups take an easy day after a particularly difficult one.

By the way, the Ache do converse and even sing during some of their search, but long distance peccary pursuits are too difficult for any talking. Basically men talk to each other until the speed gets up around 3 km/hour which is a very tough pace in thick jungle. Normal search is more like about 1.5 km/hour, a pretty leisurely pace. Monkey hunts can also be very strenuous because they consist of bursts of sprints every 20-30 seconds (as the monkeys are flushed and flee to new cover), over a period of an hour or two without a rest. This feels a lot like doing a very long session of wind sprints.

Both my graduate student Rob Walker and Richard Bribiescas of Harvard were very impressed by Ache performance on the step test. Many of the guys in their mid 30s to mid 50s showed great aerobic conditioning compared to Americans of that age. (V02 max/kg body weight is very good.) While hunter-gatherers are generally in good physical condition if they haven’t yet been exposed to modern diseases and diets that come soon after permanent outside contact, I would not want to exaggerate their abilities. They are what you would expect if you took a genetic cross section of humans and put them in lifetime physical training at moderate to hard levels. Most hunting is search time not pursuit, thus a good deal of aerobic long distance travel is often involved (over rough terrain and carrying loads if the hunt is successful). I used to train for marathons as a grad student and could run at a 6:00 per mile pace for 10 miles, but the Ache would run me into the ground following peccary tracks through dense bush for a couple of hours. I did the 100 yd in 10.2 in high school (I was a fast pass catcher on my football team), and some Ache men can sprint as fast as me.

But hunter-gatherers do not generally compare to world class athletes, who are probably genetically very gifted and then undergo even more rigorous and specialized training than any forager. So the bottom line is foragers are often in good shape and they look it. They sprint, jog, climb, carry, jump, etc., all day long but are not specialists and do not compare to Olympic athletes in modern societies.

Dr. Hill’s wonderful imagery and insight tell us part of the story, but not everything. In this day and age of gender equality, women are just as likely as men, if not more so, to be found at the gym, lifting weights, or out on the trails, running or riding a bike.

In stark contrast, hunter-gatherer women almost never participated in hunting large game animals. Nearly without exception, ethnographic accounts of hunter-gatherers agree on this point. Does this mean that women did no hard aerobic work? Absolutely not! Women routinely gathered food every 2 or 3 days. The fruits of their labors included not only plant foods but also small animals such as tortoises, small reptiles, shellfish, insects, bird eggs, and small mammals. They spent many hours walking to sources of food, water, and wood. Sometimes they would help carry butchered game back to camp. Their foraging often involved strenuous digging, climbing, and then hauling heavy loads back to camp, often while carrying infants and young children. Other common activities, some physically taxing, included tool making, shelter construction, childcare, butchering, food preparation, and visiting. Dances were a major recreation for hunter-gatherers and could take place several nights a week and often last for hours.

Table 10.1

shows the caloric costs of typical hunter-gatherer activities and their modern counterparts.

The overall activity pattern of women, like men’s, was cyclic, with days of intense physical exertion (both aerobic and resistive) alternating with days of rest and light activity. What hunter-gatherers did in their day-to-day lives appears to be good medicine for modern-day athletes. When Bill Bowerman, a well-known track coach at the University of Oregon, advocated the easy/hard concept back in the ‘60s, it was thought to be both brilliant and revolutionary. Using his system of easy/hard, athletes recovered more easily from hard workouts and reduced their risk of injury. Ironically, Coach Bowerman’s “revolutionary” training strategy was as old as humanity itself. Similarly, during the same decade, weight training combined with swimming was a stunning innovation at Doc Counsilman’s world-famous swim program at Indiana University. Now it is the rare world-class endurance coach who doesn’t advocate cross-training to improve performance, increase strength, and help prevent injury. Once again the rationale behind the success of cross-training can be found in the hunter-gatherer genes in all of us.

TABLE 10.1

Calories Burned per Hour in Hunter-Gatherer and Modern Activities

| HUNTER-GATHERER | |

| Activity | Calories Burned |

| Carrying logs | 893 |

| Running (cross-country) | 782 |

| Carrying meat (20 kg) back to camp | 706 |

| Carrying a young child | 672 |

| Hunting, stalking prey (carrying bows and spears) | 619 |

| Digging (in a field) | 605 |

| Dancing (ceremonial) | 494 |

| Stacking firewood | 422 |

| Butchering large animal | 408 |

| Walking (normal pace in fields and hills) | 394 |

| Gathering plant foods | 346 |

| Archery | 312 |

| Scraping a hide | 302 |

| Shelter construction | 250 |

| Flint knapping | 216 |