The Pacific (65 page)

Authors: Hugh Ambrose

Tags: #United States, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Pacific Area, #Pacific Area, #Military Personal Narratives, #World War; 1939-1945, #Military - World War II, #History - Military, #General, #Campaigns, #Marine Corps, #Marines - United States, #World War II, #World War II - East Asia, #United States., #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #Military - United States, #Marines, #War, #Biography, #History

The task group steamed south that evening, away from the hive of bogeys it had encountered. The reaction to this retreat by Jocko Clark, who was on board as an advisor to the new task group commander but not empowered to make decisions, was to tell the new admiral he needed a better fighter director. The morning of the twenty-third began with preparations for more incoming bogeys. When the air remained clear,

Hornet

held funeral services for two crew members who had been killed by the strafing attack. The task group steamed south along the Philippine Islands. Micheel and the wolves flew a few more missions, and the fighter- bombers got credit for one clear hit and several near misses on a troop transport before the task group set course for the fleet anchorage. The anchorage had moved to a new harbor in the Admiralty Islands.

FOR FOUR DAYS, KING COMPANY LIVED ON PURPLE BEACH, SENDING OUT PATROLS to look for snipers and awaiting orders. It sustained no casualties. The division HQ, knowing how important mail call was to morale, began sending forward bags of mail to the line companies.

279

The marines ate both C and K rations, supplemented by issues of canned fruit and fruit juice. The weather remained cool. The notes Gene kept about his experiences in battle included none of these facts. His mind was still reeling with all he had seen. The keen observer, he knew already that the battle for Peleliu was far worse than anything the 1st Marine Division had yet encountered.

From his pack he took his copy of Rudyard Kipling's poems. The sprawling, bawdy antics of "Gunga Din" no longer captivated him though. A different Kipling verse, entitled "Prelude," grabbed him.

280

In it, the poet admitted that the verses he had written about war were a bad joke to anybody who knew better. Until September 15, 1944, Sledge had been one of the "sheltered people" who had laughed at the antics of "Gunga Din" because the ballad danced past the truth he now knew. Many of the men Gene had come to love were going to die in extreme pain. His mind recoiled at the thought. Gene had sacrificed a lot to become a United States Marine. He was so fiercely proud of having bonded with the men of King Company. Kipling's question to the "dear hearts across the seas," he now apprehended, put into words the grief and bitterness in the soul of any veteran whose friends lay buried on some foreign battlefield. Private First Class Eugene Sledge was not at all sure that the death of Robert Oswalt could ever be justified. It felt like a colossal waste.

Beyond the prospect of death (his own or that of his friends), Gene saw plainly that this battle might cost him his soul. Combat reduced men to savages. Sledge respected order. He prided himself on his cleanliness of habits and mind. He did not doubt that the marines would win through to victory. In his heart he knew the stains created by what his marines were being forced to do--to kill a brother with an entrenching tool--were permanent and, perhaps, overwhelming. They had been forced to kill the war dog handler because of Japanese fanaticism and it made him hate the enemy all the more.

Gene sought solace from these thoughts by wading along the shore. He found some tiny shells he thought beautiful and decided to take a few for his mother, so she would know he had always been thinking of her.

On the morning of September 25 the remains of the First Marine Regiment began to arrive on Purple Beach.

281

Puller's marines had sustained 54 percent casualties, a rate seldom reached in warfare. As the First Marines took over Item and King's positions, Sledge heard plenty about what had happened on "Bloody Nose Ridge." All of the navy's ordnance had not destroyed the enemy's positions. To assault one pillbox meant putting the squad under fire from a myriad of other positions. The riflemen could not see the openings from which all the bullets had come. Colonel Puller had kept the pressure up, had kept ordering his marines to race into the enemy's interlocking streams of machine-gun bullets, even after his battalions had broken, his companies had shattered, his squads had disintegrated. One man said Puller "was trying to get us all killed."

282

Looking at the few exhausted, dirty men who survived, Sledge found Chesty's conduct of the battle "inexcusable."

283

In the few hours the men of King Company had with the First, the veterans of the battle for the ridge would have tried to communicate other, more specific truths. Men from the 2/1 reported that the Japanese had tried to use the 2/1's passwords and countersigns to approach their line. The 1/1 reported that "the bodies of jap officers"--the ones carrying the coveted Samurai swords--had been booby-trapped.

284

They also had determined that the rifle grenades were all defective and should be thrown away.

285

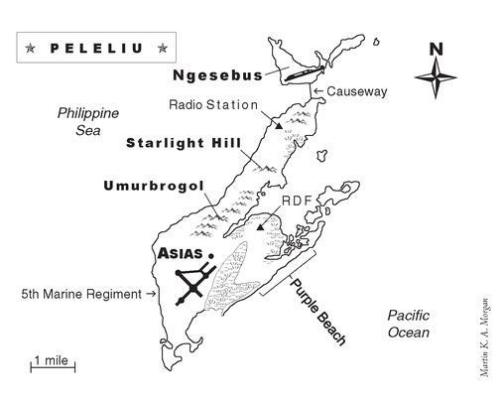

Wishing the First well, King Company walked across the narrow causeway of solid ground that led to the larger islet. The Fifth Marines' regimental HQ had been set up there.

286

Field kitchens, equipment, and the staffs of both the regiment and of the 3/5 had taken up residence there. Item Company joined them. Love Company was still in combat near the ridges.

The word was the Fifth Marines had been ordered to secure the northern end of Peleliu. Marines in combat were running short on ammunition, officers said, "so take everything you had with you."

287

At one p.m., trucks began hauling away the 1st Battalion, followed by Eugene's 3rd, with the 2nd Battalion coming later.

288

They drove back across the causeway to Peleliu, swinging southwest through the ruins of the buildings around the airfield. The division artillery was shelling the ridges to their right. The Seventh Marines were fighting into that high, broken country. To his left, service troops had set up supply depots. Gene noticed some of the Seabees looking at him. "They wore neat caps and dungarees, were clean-shaven, and seemed relaxed. They eyed us curiously, as though we were wild animals in a circus parade."

289

E. B. Sledge described himself as "unshaven, filthy, tired, and haggard." The grizzled veteran of three days in combat and four days on Purple Beach found "the sight of clean comfortable noncombatants [the Seabees] . . . depressing."

IN LATE SEPTEMBER GUNNERY SERGEANT JOHN BASILONE AND THE OTHER senior NCOs in Hawaii heard that their 5th Division had been placed on "alert status." It had to be prepared to reinforce the 1st Marine Division on Peleliu quickly, if the call came.

290

The officers of John's division held daily briefings on the Peleliu operation. Not a lot of details would have trickled out of those meetings, but the alert clearly signaled that the battle, code-named "Operation Stalemate," was not going well.

In light of the Battle of Peleliu, the focus of the men's training in the 5th Division changed.

291

Instruction in jungle warfare disappeared. The fire teams of each rifle squad hereafter honed the application of their different weapons (M1 rifles, grenades, and Browning automatic rifles), and their smooth coordination with supporting weapons (flamethrowers, bazookas, and machine guns), in the assault on hardened enemy positions. It had become clear the demolition men completed the process by hurling a satchel of C-2 explosives into it and collapsing the pillbox's firing port. Peleliu and other recent battles had also seen a high number of casualties among the junior officers (lieutenants and captains) and NCOs. The revised training schedule emphasized the need for every man to assume any role of the fire team or use any of its weapons.

292

Enlisted men in the 1/27 took a turn firing a .30-caliber machine gun and watched as someone demonstrated the flamethrower.

DESPITE THE CASUALTIES, BUCKY HARRIS REFUSED TO GIVE SHOFNER ANOTHER command. Perhaps Shifty had already guessed that his new position had to do with his performance on September 15. The companies in his battalion had been confused throughout D-day; nightfall had found two of them dangerously isolated. Shofner, when he confronted this talk, would have pointed out that some of the confusion resulted from having two 3rd Battalions (his and the Seventh's) land next to one another. When the landing craft dumped them in the wrong spot, as they often did, chaos had ensued because there were two King Companies, two Love Companies, and so on. More important, the destruction of his CP and communications equipment had severely hampered his efforts. The radios were not reliable. Such arguments, however, did not explain why Shofner had not, once he understood the situation, hiked out to King and Item companies and set it straight.

Whispers around the HQ questioned why Shofner had located his CP in an antitank trench. Everyone knew the enemy had these trenches preregistered with artillery. Poor judgment, the gossip went, had helped that mortar shell hit him. Worst of all, though, was the story that when he was hit, Lieutenant Colonel Shofner had tried to turn over his command to the battalion doctor. Word had it that, at a critical moment, Shifty had "gone bananas."

293

Had he heard the whispers, Shifty Shofner would have demanded to know how a man could be held responsible for what he said after being hit by the blast of a mortar shell. His bell had been rung. More likely, though, he knew only that before he again fought the Japanese, he would have to fight for the job.

AFTER PASSING BLOODY NOSE RIDGE ON SLEDGE'S RIGHT, HIS TRUCK TOOK A right turn and drove north, on a flat coral road running between the ridge and the ocean on their left. The 3/5 passed through an abandoned Japanese bivouac site on the shoreline, now held by the U.S. Army as it waited in reserve. A "Zippo" accompanied King's trucks farther north.

294

Named for a popular brand of cigarette lighter, the Zippo LVT had a big tank of napalm and a pump powerful enough to blow its sticky flame 150 yards. Farther along, the ridge on their right began to drop in height and back away from the road until the trucks stopped near a dense forest. They had gotten as close to the front line as a truck would take them. A few men had already been hit by sniper fire. The Fifth Marines' 1st Battalion had the task of continuing north along the road to secure a radio station area. While the 2/5 remained in reserve, the 3/5 struck off to the east to secure a conical-shaped hill that dominated the terrain. Item and King, rejoined by Love Company, broke into their skirmish lines and moved warily eastward, into the jungle. Love stayed in contact with the 1/5 to the north, where the enemy concentrated his artillery fire. King took the center and Item the right flank. They encountered a thick jungle and sporadic mortar fire.

295

It was growing dark as the rifle squads approached the sharp coral hill. In the sky above them, giant star shells opened. The navy ships were hanging five-inchers up there and all of a sudden the way ahead was visible. The enemy shrank from the light, contesting the marines' drive to the top of the hill with occasional streams of their distinctive whitish blue tracers. Another half hour of star shells allowed the men to get their barbed wire strung, because they knew a counterattack would come.

296

Creating a defensible line on the jagged landscape took time. The light made the mission so much easier; the officers who had called the navy for this help decided to call the conical hill Starlight Hill.

297

Star shells, while helpful, also created the problem of "flare blindness." As soon as the light died, the men's eyes had to refocus. Smart NCOs, therefore, learned to order one of every two men in a foxhole to shut his eyes, and thus be unaffected and ready to fire.

298

Just as expected, the Japanese attacked the front line that night. Back near the road, the 60mm mortar squads either did not have mass clearance to fire or lacked an FO, or forward observer, to aim their rounds. Artillery shells from the big howitzers in the rear began exploding in front of the 3/5's lines, effectively pulverizing the enemy. The attack broke, although one never knew for how long. Infiltrators came at the mortar section dug in near the road. Sledge saw two dark figures.

299

Burgin saw three men dive into the foxholes near him.

300

A few shots were fired and there were sounds of a struggle. When one of the figures emerged from the foxhole, he was killed. Everyone else sat tight, ready to fire.

In the morning, one marine lay dead. Sledge spoke to a number of men and arrived at a definite conclusion as to what had happened. Burgin and others disagreed, but while Sledge noted every grisly aspect of it, they knew they had to pass it off.

301

Burgin had seen the same thing on Cape Gloucester. The word came to move out. King and Love companies secured the craggy mass of Starlight Hill that morning. That night proved to be quieter and easier.

On the morning of September 27, King Company left Love and Item to hold Starlight Hill. Sledge's company marched north to support the 1/5's attack on a hill mass up there.

302

On the way up, the whole company was laughing at a story making the rounds. The previous night a scout in one of the rifle platoons, Bill Leyden, had eaten a can of Japanese food he had found in a cave on Starlight Hill. The tin of food had created an "intestinal fury" inside Bill that had led quickly to "the runs like I was going to explode."

303

On the front line and unable to move from his foxhole, Bill had had to relieve himself in empty C ration containers. He then dropped the full containers off the side of the hill. The way the story went, shouts of disgust and protest could be heard coming from the enemy below; other marines thought the voices signaled an attack, and everybody started shooting. Leyden himself enjoyed mimicking the unintelligible outrage he had heard after he bestowed his gifts before he concluded: ". . . and you know, my God, you can only imagine what he was saying. He was definitely cursing in Japanese." Everyone could relate to the story because by this time everyone had had to relieve themselves in a C ration can.