The Oxford History of World Cinema (17 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

famous director's most ambitious project. Griffith exercised as much care with the film's

exhibition. Premièred in the largest movie palaces in Los Angeles and New York, The

Birth of a Nation was the first American film to be released with its own score, played by

a forty-piece orchestra. The admission price of $2, the same as that charged for Broadway

plays, ensured that the film would be taken seriously, and it was widely advertised and

reviewed in the general press rather than the film trade press. All these factors showed

that film had come of age as a legitimate mass medium. Of course, the film attracted

attention for other reasons as well, its reprehensible racism eliciting outrage from the

AfricanAmerican community and their supporters, and offering an early insight into the

social impact that this new mass medium could have.

The narrative structures, character construction, and editing patterns of the first multi-reel

films, both American and Italian, strongly resembled those of the one-reel films of the

time. This was particularly apparent in terms of narrative structure: one-reelers tended to

follow a pattern of an elaborated single incident or plot device intensifying toward a

climax near the end of the reel. The first multi-reel American films, intended to stand on

their own, adopted this structure but, even after distribution channels became available,

longer films often continued to appear more like several one-reelers strung together than

the lengthy integrated narratives that we are accustomed to today. However, film-makers

quickly realized that the feature film was not simply a longer version of the one-reel film,

but a new narrative form, demanding new methods of organization, and they learned to

construct appropriate narratives, characters, and editing patterns. As they had in 1908,

producers again turned to the theatre and novels for inspiration, not only in terms of

screen adaptations but in terms of emulating narrative structures. Feature films, therefore,

began to include more characters, incidents, and themes, all relating to a main story.

Instead of one climax or a series of equally intense climaxes, features began to be

constructed around several minor climaxes and then a dénouement that resolved all the

narrative themes. The Birth of a Nation provides an extreme example of this structure, its

(in)famous lastminute rescue, as the Ku-Klux-Klan rides to secure Aryan supremacy,

capping several reels of crisis (the death of 'Little Sister', the capture of Gus, and so forth)

and resolving the fates of all the important characters.

However, the basic elements of the earlier films remained unchanged-credible individual

characters still served to link together the disparate scenes and shots, the difference being

that character motivation and plausibility became yet more important as films grew longer

and the number of important characters increased. Films now had the space to flesh out

their characters, endowing them with traits that would drive the narrative action. Often

entire scenes served the sole purpose of acquainting the audience with the characters'

personalities. The Birth of a Nation devotes its first fifteen minutes or so, before the

outbreak of the Civil War occurs, to introducing its major characters, seeking to engender

audience identification with the Southern slave-holding family, the Camerons. In scenes

that establish the plantation owners' kindly and tolerant natures, we see the pater familias

surrounded by puppies and kittens and his son Ben shaking hands with a slave who has

just danced for Northern visitors.

Feature films also deployed their formal elements to further character development and

motivation. Dialogue intertitles had first appeared around 1911, but their use increased so

that by the mid-1910s dialogue titles outnumbered the expository titles that revealed the

presence of a narrator; the responsibility for narration being accorded more and more to

the characters. Although the standard camera scale remained the three-quarter shot that

had become dominant during the transitional period, film-makers increasingly cut closer

to characters at moments of psychological intensity. In The Birth of a Nation, closer views

of terrified white women supposedly intensify audience identification with these potential

victims of a fate worse than death. Point-of-view editing also became standardized in the

feature films of this time. Although Griffith actually used this pattern fairly sparingly, in

two key scenes in The Birth we get Ben's point of view of his beloved Elsie, the first time

as he looks at a locket photograph of her and the second as he actually looks at her, an

irised shot of Elsie mimicking the photograph's composition.

The transition to features served to codify many of the devices that film-makers had

experimented with during the transitional period. This is particularly related to moves to

create a unified spatio-temporal orientation. Analytical editing became more common as

film-makers sought to highlight narratively important details. In the scene in The Birth

where Father Cameron plays with the puppies and kittens, a cut-in to a close-up of the

animals at his feet emphasizes the alignment of the Southern family with these appealing

creatures. Most features included some parallel editing, The Birth of course being the

locus classicus

of the form, not only in the climactic lastminute rescue that cuts among

several different locations, but throughout the film where alternation between Northern

and Southern families and the home front and the battlefield reinforces the film's

ideological message. Devices such as the eyeline match and the shot/reverseshot became

standard conventions for linking disparate spaces together, and devices such as the

dissolve, fade, and close-up became clear markers of any deviations from linear

temporality such as flashbacks or dreams.

After a decade of profound upheaval, by 1917, the end of the 'transitional' period, the

cinema was poised on the brink of a new maturity as

the

dominant medium of the

twentieth century. Films, while continuing to reference other texts, had freed themselves

from dependence upon other media, and could now tell cinematic stories using cinematic

devices; devices which were becoming increasingly codified and conventional. A

standardization of production practices, consonant with the operations of other capitalist

enterprises, assured the continuing output of a reliable and familiar product, the so-called

'feature' film. The building of ever larger and more elaborate movie palaces heralded the

medium's new-found social respectability. All was ready for the advent of Hollywood and

the Hollywood cinema.

Bibliography

Abel, Richard ( 1988), French Film Theory and Criticism.

Balio, Tino (ed.) ( 1985), The American Film Industry.

Bitzer, Billy ( 1973), Billy Bitzer: His Story.

Bordwell, David, Staiger, Janet, and Thompson, Kristin ( 1985), The Classical Hollywood

Cinema.

Bowser, Eileen ( 1990), The Transformation of Cinema, 1907-1915.

Cosandey, Roland, Gaudreault, Andre, and Gunning, Tom (eds.) ( 1992), Une invention

du diable?

Elsaesser, Thomas (ed.) ( 1990), Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative.

Fell, John L. ( 1986), Film and the Narrative Tradition.

Gunning, Tom ( 1991), D. W. Griffith and the Origins of American Narrative Film.

Jartart, Vernon ( 1951), The Italian Cinema.

Koszarski, Richard ( 1990), An Evening's Entertainment.

Low, Rachael ( 1949), The History of the British Film, 1906-1914.

Pearson, Roberta E. ( 1992), Eloquent Gestures.

Thompson, Kristin ( 1985), Exporting Entertainment.

Uricchio, William, and Pearson, Roberta E. ( 1993), Reframing Culture: The Case of the

Vitagraph Quality Films.

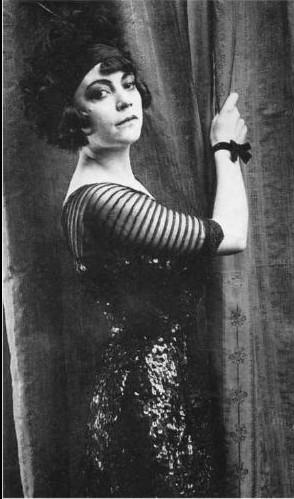

Asta Nielsen (1881-1972)

After Joyless Street ( 1925), Asta Nielsen was called the greatest tragedienne since Sarah

Bernhardt. However, her fame was established fifteen years earlier with her first screen

appearance in The Abyss (

Afgrunden,

1910), a film of sexual bondage and passion

featuring the erotic 'gaucho' dance in which Nielsen, a respectable girl led astray, ties up

her lover with a whip on stage as she twists her body around his provocatively. The Abyss

was an explosive success and Nielsen became, overnight, the first international star of the

cinema, celebrated from Moscow to Rio de Janeiro. Her performance brought people to

the cinema who had never before taken it seriously as an art form. Her personal

appearances drew crowds around the world.Born in Denmark to a working-class family,

Nielsen began acting in the theatre. There she met Urban Gad, who produced and directed

The Abyss and became her husband. The couple moved to Berlin, where Nielsen became

one of the greatest stars of the German cinema, making nearly seventy-five films in two

decades. Between 1910 and 1915, Nielsen and Gad collaborated on over thirty films,

establishing the signature style of the first period. In these early films, Nielsen's sensuality

is matched by her intelligence, resourcefulness, and a boyish physical agility. Her

expressive face and body seem immediate and modern, especially when compared with

the exaggerated gestures that were common in early cinema. Her powerful, slim figure

and large, dark eyes, set off by dramatic, suggestive costumes, allowed her to cross class

and even gender lines convicingly. She became, in turn, a society lady, a circus performer,

a scrubwoman, an artist's model, a suffragette, a gypsy, a newspaper reporter, a child

(

Engelein,

1913), a male bandit (

Zapatas Bande,

1914) and Hamlet ( 1920). She excelled

at embodying individualized, unconventional women whose stories conveyed their

entanglement within, and their resistance to, an invisible web of confining class and sex

roles. She surpassed all others in her uniquely cinematic, understated manner of

expressing inner conflict. Nielsen's celebrated naturalness was the result of careful study

in her autobiography, she described how she learnt to improve her acting by watching

herself magnified on the screen. Nielsen was a key influence on the shift away from

naturalism that characterized German cinema after the First World War. Her techniques

for conveying psychological conflict became stylized gestures emphasizing a sense of

claustrophobia and limitations. Nielsen's spontaneity slowed, her contagious smile rarely

in evidence except as a bitter-sweet reminder of her past. Close-ups now emphasized the

mask-like quality of her face. Her enactments of older women doomed and self-

condemning in their passionate attachment to shallow, younger men ( Joyless Street;

Dirnentragödie, 1927) only take on their proper resonance when contrasted to Nielsen's

earlier embodiment of young women struggling against social constaints.

Asta Nielsen

JANET BERGSTROM

SELECTED FILMOGRAPHY

(All films directed by Urban

Gad unless otherwise indicated) Afgrunden (The Abyss) ( 1910); Der fremde Vogel

( 1911); Die arme Jenny ( 1912); Das Mädchen ohne Vaterland ( 1912); Die Süden der

Väter ( 1913); Die Suffragette ( 1913); Der Filmprimadonna ( 1913; Engelein ( 1914);

Zapatas Bande ( 1914); Vordertreppe und Hintertreppe ( 1915); Weisse Rosen ( 1917);

Rausch (dir. Ernst Lubitsch, 1919; no surviving print); Hamlet (dir. Svend Gade, 1921);

Vanina (dir Arthur von Gerlach, 1922); Erdgeist (dir. Leopold Jessner, 1923); Die

freudlose Gasse (Joyless Street) (dir. G. W. Pabst, 1925); Dirnentragödie (dir. Bruno

Rahn, 1927)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Robert C. ( 1973), "The Silent Muse".

Bergstrom, Janet ( 1990), "Asta Nielsen's Early German Films".

Seydel, Renate, and Hagedorff, Allan (eds.) ( 1981),

Asta Nielsen

.

David Wark Griffith (1875-1948)

Born in Kentucky on 23 January 1875, the son of Civil War veteran Colonel 'Roaring

Jake' Griffith, David Wark Griffith left his native state at the age of 20 and spent the next

thirteen years in rather unsuccessful pursuit of a theatrical career, for the most part touring

with secondrate stock companies. In 1907; after the failure of the Washington, DC,

production of his play A Fool and a Girl, Griffith entered the by then flourishing film