The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (8 page)

Read The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor Online

Authors: Jake Tapper

Tags: #Terrorism, #Political Science, #Azizex666

CHAPTER 4

P

rivate Nick Pilozzi gasped.

Oh my God, I can’t breathe, he thought.

It was April 2006, and Pilozzi and others from 3-71 Cav’s Able Troop, led by Captain Gooding, had choppered in and been dropped atop a twelve-thousand-foot snow-capped mountain on the southern slope of the Hindu Kush for Operation Mountain Lion. The air was so thin he felt as if he were being slowly, almost subtly, strangled.

Pilozzi, who was eighteen, came from Tonawanda, New York, not far from Buffalo, so he knew from cold. But there was something devastating about the combination of the deep snow, the chill, and the lack of oxygen to be found here on the roof of these mountains. His driving skills were not needed up here; there were no cars or trucks. There wasn’t anything except for rocks and snow—anywhere from two to six feet of it. Most of the snow was packed, so the troops were able to walk on it, but they exhausted themselves digging down to rock to position their mortar tube—the cannon from which they would aim and fire explosive rounds—lest the weapon sink into the powder.

The Americans had had no idea it was going to be so cold—just one more indication that they didn’t know much about the land they were supposed to be controlling. The troops hadn’t packed appropriate cold-weather gear and had just fifteen sleeping bags for thirty men, including the handful of Marines who had joined them. They ended up dividing the bags—some got the Gore-Tex outer layer, others the thick black inner layer—and laying them atop the rock formations that jutted out of the snow. Troops clung to one another for body heat. Everyone survived, but it was the roughest night many of them had ever known. And that was how Private Pilozzi met the Korangal Valley.

(Photo courtesy of Nick Pilozzi)

The Korangal Valley was tough to get into and even tougher to get out of. The region was home to roughly twenty-five thousand Afghans, an insular community with its own particular dialect. Some Korangalis trafficked in illegal timber, selling lumber from the Himalayan cedars that grew in the valley; such traffickers were sufficiently ruthless that their influence far exceeded their numbers. The combination of this criminal culture with its geographic, cultural, and linguistic isolation had made the Korangal an inviting sanctuary for insurgents fighting the USSR in the 1980s, and then later again for those fighting the United States in the 2000s. (The Korangal was close to where those nineteen SEALs and Nightstalker pilots and crewmen had been killed in 2005, during Operation Redwing.)

Now 3-71 Cav had been diverted to the region because Colonel Nicholson wanted to take advantage of the temporary overlap, in Kunar Province, of 3-71 Cav (commanded by Fenty), 1-32 Infantry (led by Cavoli), and the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, which unit was scheduled to leave the country in late May.

Nicholson, who commanded the parent brigade, ordered 3-71 Cav to flank around the valley to the east while 1-32 Infantry blocked the valley from the north. The Marines, along with the brigade tactical command post—Nicholson, the ANA brigade commander, and a small staff—would be dropped by chopper onto mountaintops and were to clear the enemy down into the valley. Their ultimate goal was to set up the Korangal outpost, reach out to the villagers, help establish an Afghan government presence, and kill the enemy: intelligence sources claimed that the insurgent leader Ahmad Shah, thought to be behind the Operation Redwing disaster, plus a known Al Qaeda operative named Abu Ikhlas were in the immediate area.

Fenty had sent Gooding and Able Troop to watch over the southern Korangal Valley while Captain Franklin Brooks and Bravo Troop—who called themselves the Barbarians—moved south into the adjacent Chowkay Valley. Most of Cherokee Company remained back at the base at Naray, with the exception of the kill team, which was also ordered into the Chowkay Valley to patrol for enemy fighters.

The Chowkay Valley was the most popular exit route used by the Korangali Taliban to escape over the border into Pakistan; indeed, Berkoff had briefed Fenty and the 3-71 Cav troop commanders that when confronted by the consistent presence of U.S. troops, the local Taliban leader was likely to “squirt” into Pakistan, after first pushing his team of insurgent fighters into the Chowkay to clear the way for him. The Americans hoped to be waiting there for him.

After they all almost froze to death at twelve thousand feet, Gooding sent Staff Sergeant Matthew Netzel and more than a dozen soldiers from Able Troop’s 2nd Platoon down the Korangal to watch over a lumberyard. Among the troops with Netzel was Private First Class Brian Moquin, Jr., a nineteen-year-old from Worcester, Massachusetts, whom Netzel had kept an eye on since the beginning of their deployment.

When Moquin first arrived at 3-71 Cav, it was clear to Netzel that the private had been a problem child growing up—just like half the Army, in Netzel’s estimation. Back at Fort Drum, Moquin was late to formation one morning at 0630, so Netzel went to his room and banged on his door.

“What’s up, Sergeant?” Moquin said after he finally came to the door, rubbing sleep from his eyes.

“You’re fucking not at formation, that’s what’s up,” Netzel said. “Get your uniform on and get in fucking formation.”

When the slipups continued, Netzel instituted some “corrective” training, ordering Moquin to do pushups, situps, laps—anything to make his whole body hurt for a few days so he wouldn’t ever again forget what a mistake it was to slack. Netzel knew Moquin could potentially be a good soldier; he would always ask questions. After an exercise in which the troops had to disassemble and reassemble their weapons, everyone else in the platoon dispersed, but Moquin remained, repeating the drill.

“Yo, dude,” Netzel said. “It’s time to wrap shit up.”

Moquin smiled at him.

“Out of curiosity,” Netzel asked, smiling back, “what are your thoughts about how you’re hammering down on your weapon?”

“I don’t know about the rest of these guys,” Moquin said. “But I plan on coming home. And if it comes down to a weapons system working, I’m going to make sure there are no problems.”

Fuckin’ A, thought Netzel.

Born and raised in upstate New York, the twenty-five-year-old Netzel understood Moquin in a way that was hard to explain to anyone who hadn’t peered into the chasm of drug dependency and mustered the strength to walk away—in both of their cases, into the welcoming arms of the U.S. military. Back home, Netzel had dabbled in a little bit of everything, without much effect. By the age of eighteen, he’d started to sense that if he stayed in his hometown for too long after graduating from high school, he’d end up in jail or in a coffin. This wasn’t just a working-class cliché; one day, a friend of his, tripping hard, flying around a room like an airplane, dove out the window of a second-story apartment, landing on the pavement. He survived the fall but was never quite the same. Netzel headed for the military not long after that.

“I have a pretty good idea why you joined the Army,” Netzel once said to Moquin at Fort Drum. “But why don’t

you

tell me why.”

“My life was pretty much going to shit,” Moquin replied. “It was either the Army or end up in jail or dead.”

Netzel had known he was going to say that.

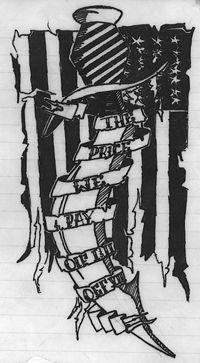

Moquin was a talented artist, and at Naray, Netzel asked him if he’d design a tattoo for him. “This is what I want,” Netzel told him. “A tattered American flag with an Afghan knife. It should also say, ‘The price we pay’ ”—this was the unofficial motto of the 10th Mountain—and should include the designations “OIF 1 and 2” and “OEF 7,” referring to Netzel’s time with the first two deployments in Iraq for Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and their current stint in Afghanistan, with the seventh rotation for Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). Moquin drew it all out on piece of paper and gave it to Netzel a few days later.

“Do you mind if I get it, too?” Moquin asked as he handed over the sketch. “Without ‘OIF One and Two,’ of course.”

Private First Class Brian M. Moquin, Jr.’s tattoo design for Staff Sergeant Matthew Netzel

(Courtesy Matt Netzel)

“Hell yeah, do it,” Netzel replied. “You drew it up, it’s your artwork. We’ll go get tatted together when we get back. So hang on to it.”

“No, I want you to hang on to it in case anything happens to me,” Moquin explained, “because I made it for you.”

“Roger,” said Netzel. “I’ll hang on to it, and we’ll get it tatted together.”

Moquin wrote to his mother:

Hi MOM,

How’s everything, I’m doing good. I’ve done a lot of thinking while I was here. I know I haven’t been a great kid and have put you through a lot of things that you didn’t deserve. I haven’t been a good person to many people and I regret a lot of the things I’ve done. But I finally found a place for me. I love it here more than anything. I’ve wanted to get away for so long, I was trapped in my own misery and selfishness. I’ve grown up a lot here, and I’m going to try my damn hardest to make you proud of me. I’m sorry if you don’t hear from me much. I’m very busy and I’m going to be for the next couple years. I love you and I just wanted you to know I haven’t forgot about you.

I’m doing the best I can to be the best soldier.

I miss ya,

Love, your son,

Brian.

And now here they were in the Korangal, Netzel and Moquin, in four feet of snow. Almost none of the other soldiers had been in combat before, so Netzel, having been in Iraq, took the lead as they began their trek.

For nearly all of the troops, the steep mountain descent—during which each soldier carried eighty pounds of gear and ammo at a minimum—was one of the toughest physical challenges of their lives. (And these were young men in top physical condition, trained for just such a challenge.) They had to worry constantly—about falling, about the enemy, and about the clumsy morons up above them (someone up top would accidentally kick a rock loose, and then everyone would shout “Rock!” and try to dodge getting hammered by a mini-boulder). It was a painful, full-day hike down. Climbing

up

the mountain would have been easier.

On the fifth night, the members of the platoon reached one of the most difficult points so far in their journey, confronting a cliffside so steep they couldn’t descend. They decided to call it a night. In the morning, they’d figure out where to go next.

Sergeant Michael Hendy was on guard duty; he sat behind a rock wall in the pitch black, staring at the path. He heard a hissing.

“I think a battery’s leaking,” Hendy whispered to Moquin. Batteries for the thermal scope were stacked up for the night; filled with a gas, they would make a

“Ssssss”

sound if they cracked. Hendy turned on a thermal light so he could fix the problem. A four-foot-long pit viper was angrily staring him in the face, raised as if it were coming out of a snake charmer’s basket.

Holy shit,

Hendy thought.

He jumped back and told the lowest-ranked private, Taner Edens, to get the snake. Edens snatched up a KA-BAR combat knife.