The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (31 page)

Read The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor Online

Authors: Jake Tapper

Tags: #Terrorism, #Political Science, #Azizex666

Skepticism was far from exclusive to the locals. Many American experts were uncomfortable about the fact that so much of the effort to bring peace to the region now rested on the shoulders of Fazal Ahad, who they believed was motivated only by the desire to get his hands on development dollars. Adam Boulio in particular viewed him as a shady character: Ahad simply isn’t our friend, he thought. His speeches in the shura meetings often seemed to contradict and counter American aims, and Boulio believed that Ahad’s influence actually turned some neutral elders against the United States and the Afghan government.

The soldiers of Able Troop spent the winter months trying to make inroads among the villagers of Kamdesh, distributing bags of rice, beans, and flour as well as teacher and student kits. Officers at Combat Outpost Kamdesh were even asked to help facilitate a visit by Kushtozi elders to Kamdesh Village, to help broker peace between the warring communities of the Kushtozis and the Kom.

By now, 3-71 Cav had been in Afghanistan for just over a year. The troops were spent and demoralized and still in mourning for their lost comrades. But at least they could console themselves with the knowledge that their deployment was almost over. To prepare for the redeployment back to Fort Drum, several hundred soldiers from across the 3rd Brigade—including a couple of dozen from 3-71 Cav—had already started moving back to the United States via Kuwait and Kyrgyzstan. A few had even spent a couple of nights back home with their families.

Gooding, for his part, had been called to Forward Operating Base Naray for a commanders’ huddle to plan for postdeployment training at Fort Drum. It was the first time all of the commanders had been together since they pushed out of Forward Operating Base Salerno in March 2006, and their reunion had a celebratory air.

And why not? They were getting the hell out of Dodge. Berkoff had purchased a plane ticket and booked a week’s vacation in Cancún with some college friends. He’d given his counterpart in the 82nd Airborne—which was supposed to replace 3-71 Cav at Naray—his DVDs, his books, and even his bunk. (Berkoff had moved from his little hooch to a tent near the landing zone.)

In the middle of the night on January 22, 2007, the staff and commanders were told to report to Howard’s office. As he watched Captain Frank Brooks get up from his cot and head to the lieutenant colonel’s office, Erik Jorgensen worried that they must have had a KIA. But no artillery was firing, Jorgensen noticed. And no one was out. Maybe there was an urgent mission of some sort? What was going on?

This was what was going on: the political dominoes had fallen, and as always, the joes in the field were the ones knocked facedown on the floor by the last game tile.

Two and a half months before, back in the United States, the Republicans had taken what President Bush referred to as “a thumpin’ ” in the November 2006 elections, with the downward trajectory of the war in Iraq’s being seen as one of the major contributing factors in the Democrats’ recapturing of the House and Senate. A head had to roll, and Defense Secretary Rumsfeld offered his up. The brand-new secretary of defense would be Robert Gates, the president of Texas A&M University and former deputy national security adviser and director of the CIA for Bush’s father, President George H. W. Bush.

A few days before the leaders of 3-71 Cav were summoned in the middle of the night to meet with Lieutenant Colonel Howard, Gates had visited Afghanistan and met with commanders on the ground. Lieutenant General Karl Eikenberry, the outgoing commander of the U.S. Combined Forces Command Afghanistan,

31

requested that the tours of thirty-two hundred soldiers from the 3rd Brigade—including all four hundred troops from 3-71 Cav—be extended for up to 120 additional days in preparation for an anticipated Taliban spring terror offensive in the southern and eastern parts of the country. It wasn’t easy for Eikenberry to ask for the extension, but it was his only option, as the war in Iraq remained the Bush administration’s main effort. Gates agreed.

“Although it is going to be a violent spring and we’re going to have violence into the summer, I’m absolutely confident that we will be able to dominate,” Eikenberry declared.

So there they all were, in Howard’s office: Gooding, Brooks, Schmidt, Stambersky, Berkoff, Sutton, and others. Howard got to it quickly.

“Our deployment has been extended four months,” Howard told them. “The new secretary of defense wants and needs more troops here, and there are no others—we’re the only combat brigade that’s ready, and all the other units are committed to Iraq.”

Gooding began trembling. It was the same feeling he had when he lost a soldier. He was certain that this decision would mean at least one of his men would die.

Berkoff later wrote to his friends and family:

No words can describe how I felt when I was shaken out of a cold sleep, only to be told that we’ve been extended another four months. I should have realized something was up when we just received a new shipment of uniforms that were long overdue. I’m sure the Defense Sec. Gates, who’s been in his office for all of two weeks and came out here to visit, listened to some NATO general say that we needed more troops in Afghanistan—and that’s it. The entire 3rd Brigade, and the 10th Mountain HQ, all ordered to remain. We are now calling back hundreds of soldiers who already went home to return to their posts out here. All our equipment that we sent away, it’s coming back, or so we hope. It’s just unreal. God help the man who made this decision when we lose another soldier…. All I can say is that I’m sorry for what we’re putting you through. I’ll be home one day, and if no one else is hiring in the market, I know a few guys here who would make outstanding Bush Administration Protesters for a living.

Captain Brooks returned to his tent with a grim look on his face. He sighed and said, “Someone get all the platoon leaders and platoon sergeants.”

Five minutes later, sleep-deprived and dazed, the Barbarians’ platoon leaders and sergeants heard the news from their commander.

“Listen, guys, there’s no easy way to say this: we’ve been extended another four months,” Brooks told them.

No one spoke; everyone was dumbstruck. Jorgensen was supposed to get married in two months’ time, and Brooks himself two months after that. Neither would be able to make his own ceremony.

Gooding called Combat Outpost Kamdesh and asked for First Sergeant Todd Yerger. He broke the news to him, though Yerger had already seen some emails about it. The sergeant huddled the troops together. He told them he had good news and bad news.

“The bad news is you aren’t going home,” Yerger said. “The good news is you’ll get paid an extra thousand bucks a month.”

The men were devastated. Some began to weep.

Back at Naray, Jorgensen sat on his cot and let it all sink in. He pulled on his shoes and walked out toward the phones to call his fiancée, Sheena, and his parents. Turning the corner, he saw a line for the phone that would take hours. So much for that.

He went back to the troop command post and hopped onto the computer to email Sheena and his parents:

I really don’t how to say this, so I’m just going to come out and say it…. We’ve been extended. We’re not coming back until June now. I think the most obvious thing is that the wedding will have to be postponed. This info is about three hours old right now, so I don’t have a lot of answers. Normally I’d call for something this important, but the phone line has 150 people in it right now and it’s only getting longer. I really don’t know what to say right now, we’re all still in shock. I’ve got to go now and talk to my soldiers, a lot of them aren’t taking it well. I love you guys.

—Erik

Jorgensen’s captain, Brooks, was one of those soldiers not taking it so well. Right before Lieutenant Colonel Fenty’s helicopter went down, Brooks had been talking to his first sergeant about how he was convinced—had always been convinced—that his girlfriend, Meridith, was “the one.” After Fenty and the other nine men died and Brooks got off the mountain, he found the first phone he could use and called her. “I can’t tell you what’s going on, but we had a pretty bad event happen, and it’s made me realize—will you marry me?” he asked her. “Yes,” she said. They soon picked a date: June 9, 2007.

Now Brooks was calling her again, this time to tell her that his deployment had been extended and they would have to postpone their wedding. She’d already moved to upstate New York and set up an apartment, believing he’d be there in February. She was distraught, and they both wept. “I don’t believe you,” she cried. “Why is this happening?”

The move was a surprise and not a surprise. Speculation about an extension had been swirling for weeks, but the anxious troops of 3-71 Cav had been told not to worry. Major General Freakley had visited Forward Operating Base Naray on Christmas Day and given them a short speech: “Gentlemen, I know there are a lot of rumors out there about us getting extended,” Freakley said. “Let me be the first to tell you: we will all go home in February!”

He was half right. Freakley himself did go home in February. The men of 3-71 Cav had to stay until June.

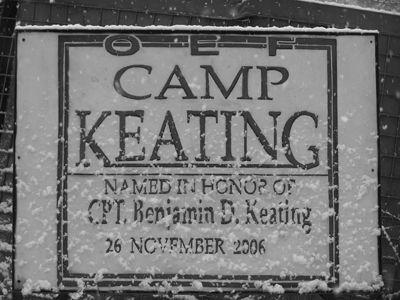

The priest had been FOB hopping, flying from base to outpost, tending to the soldiers’ spiritual needs as best he could. It was hardly an ideal situation for either the clergyman or his flock, but “ideal” as a concept had been tossed out the window the first day American troops set foot in Afghanistan. Now he was here on a particularly chilly day for the renaming of this outpost in the Kamdesh Valley. It would henceforth be known as Combat Outpost Keating.

“We ask your blessing on the dedication of this camp in the memory of First Lieutenant Benjamin D. Keating, a risen warrior of Able Seven-Three-One,” the chaplain prayed during the ceremony. Of course, the squadron wasn’t 7-31, it was 3-71, but the chaplain repeated his mistake: “Thank you for the service and sacrifice of Able Seven-Three-One,” he said.

What would Ben Keating have made of such an error? He would likely have rolled his eyes and had a laugh at the Army’s expense. He had given his life for the Army, and the Army couldn’t even get the name of his squadron right.

Gooding had been mired in his own misery after Keating’s death; it had taken him a month or so to snap out of it. After he did, having recognized the pit of despair in which he’d been trapped, he was thankful that his depression hadn’t come during fighting season. During the ceremony, he tried to keep his tone positive. He unveiled the wooden sign identifying the camp as Combat Outpost Keating—the wood had been cut by Billy Stalnaker, the design was by Specialist Jeremiah “Jeb” Ridgeway—and said that Keating would have been honored.

The Kamdesh outpost was named in honor of First Lieutenant Ben Keating, promoted posthumously.

(Photo courtesy of Matt Netzel)

It was a rough winter for Captain Matt Gooding.

(Photo courtesy of Matt Netzel)

Tens of thousands of miles away, in Shapleigh, Maine, Ben Keating’s parents, Ken and Beth, were ambivalent about the dedication. They understood the desire of the men of 3-71 Cav to honor their son and, perhaps, to lift their own spirits as they faced the depths of winter at Kamdesh. However, the Keatings had no illusion that the camp would be a permanent fixture in the landscape of Nuristan. (Gooding had mulled over this issue, too.) The monument for their son would be, one way or another, short-lived. The next company would have no idea who Ben Keating had been. New leadership might decide to abandon Combat Outpost Keating altogether. And the site, because of its vulnerability, might be overrun. Indeed, it was the location of the outpost that seemed to trouble Beth Keating the most. She didn’t like the notion of her son’s memorial’s standing in such a horribly dangerous part of the world. She was touched that the men Ben had served with had felt so strongly about him, and so affectionate toward him, that they wanted to honor him, and she knew there were limits to what they could do. But it was almost as if someone had decided to rename a sinking ship after her beloved boy just as it slipped below the waves.