The Outlaws of Ennor: (Knights Templar 16) (2 page)

Read The Outlaws of Ennor: (Knights Templar 16) Online

Authors: Michael Jecks

Tags: #_MARKED, #_rt_yes, #blt, #Fiction, #General

To you all – my sincere thanks!

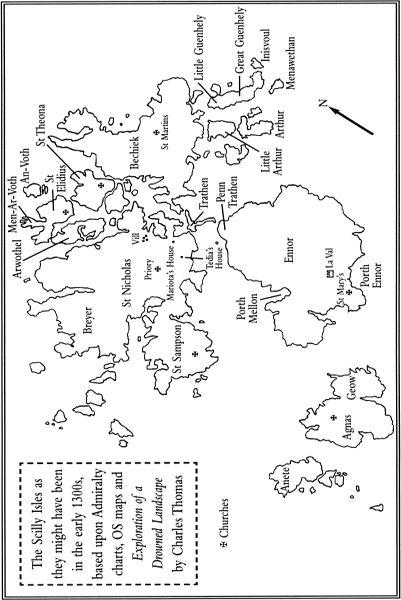

| Abbey | Since AD 981 Tavistock Abbey had owned the northern parts of what was then known as Ennor. It is likely that at this time, the Scilly Isles were all one land mass, one big island, and that only later did it separate as the sea rose. From that time, the northern islands became the Abbey’s, administered through the Priory of St Nicholas. |

| Clinker | The sides of ‘clinker-built’ ships were constructed with overlapping long planks or ‘strakes’. Each strake was laid with the overlap at the lower edge on cogs (see Cog below) and most ships, other than hulks (see Hulk below), which curiously had the overlap at the top edge. The gaps between each strake were filled with a fibrous material known as ‘caulking’. This would be made more watertight by smothering it in tar. |

| Cog | A medieval vessel with a flat bottom, straight stems fore and aft (rather than bowed), and clinker-built sides. These boats were particularly common in northern climates, less so in the Mediterranean. |

| Gather-Reeve | The men involved in the administration of a district like Ennor could have many responsibilities. The ‘gather-reeve’ was effectively the rent-collector, or tax-man. |

| Glebe | An area of land given to the Church for the support of a local priest. |

| Grapnel | A set of three or four large metal hooks lashed or welded together and attached to a rope so that when thrown, they would invariably snag. They were used to help board ships. |

| Halyard | The rope used to raise or lower the yard. |

| Havener | An official of the Earl of Cornwall who administered the revenues from the seas. He took the rents from those men who were happy to pay, in order to collect the Earl’s income at seaports; he imposed fines on those who grabbed what they could from wrecks; and he ran the Earl’s maritime courts, taking the profits for the earldom, among other duties. It was a post unique to Cornwall, partly due to the length of coastline, and partly because of the privileges enjoyed by it. |

| Hogged | When a ship was ‘hogged’, she drooped down fore and aft, showing that her inner strength was gone. |

| Hulk | A vessel in which the strakes met at the topmost level of the ship’s side (the sheer) rather than at a stem. On hulks each strake overlapped on the upper edge, not the lower. |

| Keel | This ship had a keel, stems, and clinker design which met at stems fore and aft. She had a rounded bottom, and was the same shape as a ‘Viking’ longboat. |

| Priest’s Mare | A cleric’s concubine. |

| Ratlines | Rope steps, spliced into the shrouds to allow sailors to climb up to the sail. |

| Sheer | The topmost edge of the hull. |

| Sheet | A rope attached to the sail’s bottom corners. By controlling this, the angle of the sail to the wind can be altered, thus giving greater manoeuvrability. |

| Shroud | A rope running from the top of the mast to the ship’s side, giving side-to-side strength supporting the mast itself. |

| Stay | Running from the top of the mast to the front or back of the ship, these ropes gave the mast strength fore-and-aft. |

| Pilgrims and Travellers | |

| Baldwin de Furnshill | A former Knight Templar who is now the Keeper of the King’s Peace in Crediton. Baldwin is travelling homewards after a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. |

| Simon Puttock | The Bailiff of Lydford Castle in Dartmoor, Simon joined his friend Baldwin on pilgrimage, and is looking forward to taking up a new position in Dartmouth on his return. |

| Sir Charles of Lancaster | Although he was once a proud knight and supporter of Earl Thomas of Lancaster, since Lancaster’s death Sir Charles has become a wanderer. He met Baldwin and Simon in Galicia, and is now returning to seek his fortune in his homeland. |

| Paul | Squire and general man-at-arms to Sir Charles, Paul is glad to be on his way home. |

| Gervase | Master of the Anne , Gervase is an experienced and wily captain of his ship. |

| Hamo | Only young, Hamo is learning his trade as a sailor. For now, when there is a supercargo, he acts as cabin-boy and steward to the master. |

| Jean de Conket | A Breton, Jean is a determined and resourceful leader of his pirates. Desperate for a successful voyage, he is reluctant to give up his prize. |

| Inhabitants of the island of Ennor | |

| Ranulph de Blancminster | Master of Ennor Castle, and tenant-in-chief of the islands, Blancminster is the most powerful secular man on the islands. Trouble brews between him and his counterpart on St Nicholas, the Prior, when they dispute territory or responsibilities. Ranulph is responsible to the Earl of Cornwall for Ennor, Agnas, Geow and Anete, but holds jurisdiction over the Arthurs, the Guenhelys and other outlying islands not owned by the Church. |

| Thomas | Sergeant to Ranulph, Thomas is his most senior official. Over the years he has won a position of power over the secular islands. |

| Robert of Falmouth | The gather-reeve of Ennor, Robert is as unpopular as any taxman must be, largely due to the reputation given to him by his master, Thomas. |

| Walerand | Once a petty thief, he was forced to run when he drew a knife on a priest in the local church. Now he has a position in Ranulph’s castle, but he is ambitious and craves power and money. |

| William of Carkill | The former chaplain of St Elidius, William is now responsible for the small church of St Mary’s on Ennor, but his loyalties remain with the poor folk of the islands, not with Ranulph and his men. |

| Hamadus | Old fisherman, and now sexton to William at St Mary’s. |

| Inhabitants of the island of St Nicholas | |

| Tedia | A woman who adulterously falls in love with Robert, the gather-reeve. |

| Isok | Tedia’s husband; one of the island’s most capable fishermen and a clever mariner. |

| David | As reeve, David is the leader of the vill in which Tedia lives. He too is a capable seaman. |

| Brosia | The bored wife of David, Brosia is narcissistic and not averse to a little dalliance with other men. |

| Mariota | Tedia’s widowed aunt. |

| Priory and other Religious | |

| Cryspyn | The Prior at the priory of St Nicholas, Cryspyn holds a senior position, effectively owning the whole of the islands of St Nicholas, St Elidius, St Sampson, St Theona, Arwothel and Bechiek. He holds these lands under the authority of the Abbot of Tavistock. |

| Luke | The chaplain of Tavistock Abbey’s little chapel on the island of St Elidius, Luke was sent here as punishment for his grave offences in England and Ireland. |

Anyone

who has walked on the Scilly Isles cannot fail to be struck by their beauty. The isles have a strange, welcoming tranquillity which does not exist elsewhere. Certainly the atmosphere is marvellous for a holiday. It feels as though you are stepping back in time to a quieter, more peaceful era.

In large part the attraction of the islands is their emptiness. The Scillies have had a checkered history; some islands were evacuated – sometimes willingly, sometimes with whole populations forcibly removed and sent away, although not always by humans. The elements have often played their part.

Research shows that the Scilly Isles have progressively reduced in size as the sea has overwhelmed them. They are not a fixed group of rocks in the middle of the ocean, they are an ever-changing mass, with the sea occasionally washing over them and devastating huge swathes. This is not the place for a dissertation, but Charles Thomas’s book on the subject is essential reading for those who are keen to learn more. The evidence suggests that the Scilly Isles were once one larger mass, probably called ‘En Noer’, or ‘The Land’ in old Cornish. Over time, the sea encroached and flooded the lower plains in the middle of the island, until now we have a scattering of islands set about a shallower central pool. For a suggestion of how the islands may have looked, see the map on

page xviii

.

It is always a delight when research leads to new ideas. Charles Thomas’s book led me directly to the connection with poor Brother Luke, the survivor of

Belladonna at Belstone

(Headline, 1999), and instantly I formed an idea of his continuing adventures. At the same time, I had recently read Frederik Pedersen’s book about marital disputes in medieval England, and the startling nature of Tedia’s marriage and subsequent divorce seemed to tie in with that subplot.

However, most of this story is about the islands, and the type of

men and women who can survive in such a place. There is something different about island people: they are constrained by their geography. Youngsters on St Mary’s still have no access to things which are viewed as essential by their counterparts elsewhere in the British Isles: motorways, for example.

If modern youths bemoan their fate living on an island, how much more would their ancestors have to gripe about? They lacked even the means of self-support. Subject to any tax imposed upon them by an outrageous master, these peasants were tied to their land and had only one law, that of their master, Ranulph de Blancminster. We know little about him, but that little we do know is not flattering to his memory.

The Coroner, William le Poer, said that he received ‘felons, thieves, outlaws and men guilty of manslaughter’. We know that after this particular complaint an enquiry was held into Blancminster’s actions, but the result was not conclusive. Then, presumably in revenge, in 1308 le Poer was arrested by Blancminster and held in the gaol at La Val, only to be released when he paid a fine of 100 shillings. This supposedly because he had carried away a whale which had cast up on Blancminster’s lands.

At this time the law was very confusing. For example, wrecks which landed on St Nicholas (which in our day is called Tresco, but would have included Samson and Bryher), or on the other northern elements of the priory’s lands, such as St Martins, St Helens and Tean, were the property of the monks at the priory. Wrecks which hit the rest of the islands should have been the property of the Earl of Cornwall, and the Earl would usually have demanded his money. Whales, however, were different. They, together with grampuses, porpoises and sturgeon, were considered ‘royal fish’. Wherever they were found, they were supposed to be sent to the King’s household. This didn’t always work out. In the case of Cornwall, because the earldom had been held by a member of the royal family, certain privileges were possessed by them. The right to royal fish was jealously guarded, and the Earl’s Haveners would always seek out any such prizes.