The Ouroboros Wave (2 page)

Soon after Kali was discovered, the Black Hole Reconnaissance Group of COSPAD, the UN’s Cosmic Space Development Agency, was formed as a dedicated observation group. It was BHRG that first proposed the artificial accretion disk development plan. It then dissolved itself, only to immediately reemerge as AADD.

That was in 2120.

BHRG quickly discovered something unusual about Kali: it had a high probability of colliding with the Sun in anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand years. The lack of precision in the estimate was due to Kali’s size. Calculating its orbital elements by standard methods was dauntingly difficult, but computer simulations confirmed that at some point the black hole was destined to

fall into the Sun.

BHRG’s proposal was to shift Kali out of its collision course and onto a trajectory that would make it a satellite of Uranus. At the same time, placing an artificial accretion disk around Kali would meet all of the solar system’s energy requirements for as long as

anyone was willing to guess.

The concept met with little interest at first; few considered it even feasible. Kali would not fall into the Sun for centuries, maybe even for thousands of years. It was hard to see it as an immediate threat. There was also little consensus concerning the physical effect of a tiny black hole colliding with the Sun. BHRG’s proposal

seemed dead on arrival.

Yet the scientists behind it were nothing if not determined. All of BHRG’s original members were astronomers, but theoretical physicists and others soon began to join, forming a network that stretched throughout the solar system—a network of experts from the wide range of fields that would ultimately be needed for the construction of an artificial accretion disk. A development group quickly formed, with BHRG as its nucleus. Only a few of its members hailed from Earth, but they made up for their limited numbers in quality. As the group expanded across the solar system, membership expanded beyond the scientific and engineering community to include economists, psychologists, media specialists, and others. Ultimately AADD emerged as the official representative

of this unofficial network.

This was the notion of AADD’s foundation accepted by most

Terrans. The reality was different.

Long before AADD was founded, Mars settlers were building a flexible, project-driven society starkly different from Earth’s hierarchical class systems. Terrans tended to think the UN created BHRG, which then spawned AADD. In truth, the two groups were both born of United Nations decisions; the UN could be said to be the common ancestor of both. Colonists throughout the solar system had fused their individual development plans for each planet into a system-level agenda, and were coordinating to implement it. They created BHRG as one arm of this effort, used it to engage in a wide range of research, and finally created AADD as a concrete

expression of that R & D network.

Given the nature of the project, most of AADD’s members were from Mars or the asteroid belt. Many of its members from Earth eventually migrated offworld. Terran civilization had become extremely conservative. Preservation of established norms—and protection of established interests—was equated with virtue. The result was a kind of soft fascism that combined quasi–free market economies with authoritarian political control—not exactly an ideal environment for inquisitive scientists. Anything questioning the existing constellation of powers was a threat. The scientific community was strictly hierarchical, and research was allowed only in certain fields. The important thing was not productive science, but protection of the status quo.

For the promising young scientists and engineers who sensed the dangers of this system, the freedom offered by BHRG’s philosophy was even more attractive than the prospect of working on accretion disk technology. Those who left Earth were seen as traitors. Other young researchers were branded as undesirable elements and forcibly deported offworld.

By the time AADD was established, plans were in place for what would become Ouroboros. From this point on, the artificial accretion disk and terraforming of the Martian surface were part of a single vision.

The accretion disk would be completed in thirty years, with another half century to terraform Mars. The eighty-year timeline kept the project within the lifetime of the investors. Once the accretion disk was producing energy, AADD would have its own source of revenue. The question was how to finance the project until then. AADD’s solution was to entice investors with profits from rapid appreciation of real estate on Mars and the main asteroids, terraformed through energy provided by Kali. This incentive became the key to obtaining financing for the project. Chandrasekhar Station—beginning with the construction of Ouroboros—was the first step on a path that would continue for decades.

“

WE WON’T HAVE TIME

to mourn Graham after today, will we, Tatsuya?”

“That’s how it is with any project like this.”

Catherine and Tatsuya were on the ring’s maglev, bound for South Platform. Nicknamed “the bullet” by the construction crews, the maglev provided rapid transportation between platforms. There were several other smaller vehicles, single-seaters dubbed “trucks.” Both systems moved at satellite speed, covering the three-thousand-kilometer distance between platforms in under twenty minutes.

Viewed from the equinoctial point above Ouroboros, both bullet and ring would be revolving clockwise. Since they were traveling in the direction of rotation, Catherine and Tatsuya sat opposite each other at a table attached to the side of the train that was away from the ring. The train was pressurized and was often used as a temporary habitat as well as for transport. The door to the compartment was flanked with small lockers flush with the wall, with storage for emergency oxygen and coffee mugs labeled with

the names of their owners.

Keeping the compartment clean was the responsibility of the users. While things were reasonably tidy, the walls were marked with stains from what might have been sauce that floated, weightless, through the compartment when the bullet had stopped while

someone was eating.

“Okay, we’re under the gun. But SysCon has more to do than just make up lost time. We’ve got to turn detective and find out

why Graham was killed.”

“Like in those whodunit softs you love to read? Figure out the killer from a speck of dust or some other microscopic bit of

evidence?”

“Yes, but that’s not enough. We can’t just wait for suspects to get killed off one by one before we nail the culprit. We’ve got to work out a solution before someone else becomes a victim. Like

Sherlock Holmes. Do you follow, Watson?”

“I don’t know. Holmes was a genius who could run rings around

the experts. But this is real. It’s up to the Guardians—”

“It’s up to us too. I’ve already briefed them, but they can’t do anything about this on their own. There’s an AI in the mix here. You sense it too, don’t you? There’s something very wrong about

this accident.”

“I guess. There’s no way Graham could have fallen off the ring. It’s physically impossible.”

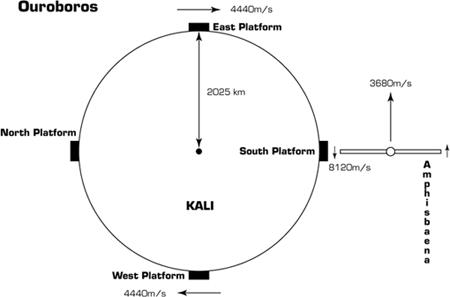

Ouroboros, the first stage in the Chandrasekhar Station project, was a five-meter-wide ribbon of metal stretching almost 13,000 kilometers around Kali at a radial distance of 2,025 kilometers. Scale the ring down to a diameter of one meter, and a few dozen atoms laid end to end would be enough to span its width. This metallic thread, with Kali at its center, was rotating clockwise at 4,440 meters per second. Because of its continuous ring shape, Ouroboros had no net gravitational interaction with Kali and was vulnerable to anything that might alter its position. Without active stabilization, Ouroboros would begin to oscillate and sooner or later fall into the black hole. To prevent that, the ring could alter its shape

dynamically, damping any undesirable resonant energy.

North Platform had been constructed first. Then the ring was extended clockwise along the path of orbit with three more platforms built at ninety-degree intervals. Each platform incorporated nuclear fusion for power, data processing, and communications equipment, and life-support systems for the safety and comfort of the building and maintenance crews. North and South Platforms were mainly living quarters. East and West Platforms emphasized infrastructure and support equipment. AIs to control the ring stabilization system were deployed east and west, facing each other across the ring. But at the moment only AI Shiva, on East Platform, was fully functional. AI Sati, its opposite number, was still in final testing.

“That’s right. As long as you’re on the ring, it’s impossible to fall into Kali. You’re in free fall around it. But that’s not what bothers

me about this accident. Did you read SecDiv’s analysis?”

Dr. Chapman’s fall into Kali was a conundrum. How had it happened? Tatsuya had already received the Security Division report. The time stamp showed that it had arrived just before the

funeral.

Chapman had taken a truck to East Platform, where he had apparently input some modifications to Shiva. After Chandrasekhar Station was complete, its orientation and positioning systems would be distributed to avoid reliance on a single AI. But for now it was up to Shiva to keep the ring stable. To prevent tampering with such a critical system, the AI’s programs couldn’t be modified remotely. Modifications could only be done by authorized personnel physically

present on East Platform.

Whatever his objective had been, Chapman had fulfilled it, then boarded the truck and begun retracing his route. Yet he went only partway before turning back. Judging from his actions, he must have realized that there was some flaw in the modifications he’d made. Evidently he’d been desperate to return right away, for he removed the truck’s console cover and forcibly disconnected the

speed governor. The truck’s speed quickly exceeded safe limits.

By disconnecting the governor, Chapman had taken the truck off-line—which prevented Shiva from detecting it as it came hurtling back. Instead, the laser cannon radar array picked it up. Shiva’s log later showed that the AI had mobilized all of its reasoning capacity to determine that the approaching object was in fact a truck and not a meteor. Then it had searched for a way to gain access to the truck’s power control. It found one—and stopped the truck dead

in its tracks.

Chapman would have been killed instantly, the truck torn to pieces by its own inertia. Its fragments, along with Chapman’s body, hurtled toward the temporary crew modules atop East Platform. The kinetic energy of the pieces and its erstwhile human cargo demolished the modules instantly, producing two types of wreckage. The module debris took an elliptical course toward the interior of the ring. The rest—including what had once been Chapman—hurtled toward the black hole. By now, most of the debris had already been transformed into a gaseous ring by Kali and was flowing into the black hole, sweating X-rays as its atomic structure was disrupted

by the immense tidal forces.

For now, that was the sum total of what was known about the

accident.

“Based on this report, Graham was messing with the speed

control,” said Tatsuya.

“That’s not the problem. Shiva would assume mechanical fault in a case like that. He should’ve decelerated the truck gradually. We’ve had a few glitches with the trucks and the bullet, and that’s how Shiva has always handled them. This is the first time he’s behaved like this. Sure, yanking the limiter circuit created a problem, but not with the truck. The problem is how Shiva responded. SecDiv doesn’t have the tools to get to the bottom of this. This is all about

Shiva’s reasoning processes.”