The Other Anzacs (30 page)

The cost of that first day soon became clear. On Day 2, 20, 000 casualties came through Rouen, and hospitals at Boulogne and Le Havre took in thousands more. Because of the appalling numbers, it was only possible to keep and care for the worst of the wounded. The rest went straight to England on hospital ships. English war correspondent Philip Gibbs visited the hospital at Corbie, near Amiens, christened the ‘Butcher’s Shop’ by a colonel of the Royal Army Medical Corps who invited Gibbs to have a look. The correspondent found himself ‘trembling in a queer way’. What he saw sickened him.

In one long, narrow room there were about thirty beds, and in each bed lay a young British soldier or part of a young British soldier. There was not much left of one of them. Both his legs had been amputated to the thigh and both his arms to the shoulder-blades . . . another case of the same kind; one leg gone and the other going, and one arm . . . I spoke to that man. He was quite conscious, with bright eyes. His right leg was uncovered, and supported on a board hung from the ceiling. Its flesh was like that of a chicken badly carved—white, flabby, and in tatters. In bed after bed I saw men of ours, very young men, who had been lopped of limbs a few hours ago or a few minutes, some of them unconscious, some of them strangely and terribly conscious, with a look in their eyes as though staring at the death which sat near to them, and edged nearer.

22

Trains were commandeered and the wounded were brought in by any means possible. One of the sisters doing train duty was Annie Shadforth, who had ‘heard the great barrage’ that announced the opening of the battle. Annie had a busy time collecting patients from various casualty clearing stations and unloading them at the different base hospitals, on each trip carrying between 500 and 600 patients. This went on for a fortnight. At the Gazencourt clearing station, she found the grounds, as well as the tents, packed ‘and ambulance cars and a small train almost like a toy train bringing in more’.

A guard had to be placed all around the train as the poor boys were so anxious to get away from it all back to the base and perhaps further on to Blighty. But the ones there were wounded badly [and] had to have the first attention and these patients were put on the trains before less severe wounds. We had a good many deaths during that time on the train although if we noticed a patient not [doing] very well the [commanding officer] had the train pull up at a station at the nearest point to a hospital and the patient taken off there.

23

On one shift alone, Alice Ross King reported 500 admissions to her ward. ‘I have one man who is quite mad. He got into the 4th line of German trenches and went to take some prisoners. They cried mercy and while he hesitated one threw a bomb right into his face. The fire enveloped him and he says he lay there grovelling in the earth. For two days he was not picked up and today when we took his dressings down his eyesight was not gone. He wept for joy.’

24

The sight and sounds of the wounded were heartbreaking. ‘Nearly all the boys are a bit mad and they all talk nonsense, ’ Alice observed. ‘One beautiful fair haired boy who had his leg off yesterday was crying wildly, “Bulldog breed sister. Boys of the Bulldog breed. We mustn’t let them beat us sister.” It’s very pathetic.’

25

Going to church, Alice was distracted. She found she ‘could not get into sympathy’ with the organ. Emerging, she ran into four 5th Division artillery officers, whose train had arrived at 8 a.m. and was not leaving until 4 p.m. ‘To think that Harry had not had that luck!’ she lamented. ‘All day long my thoughts have been with him but I have had no letter. I cannot think that he would so neglect writing to me if he really cared for me. Still it is a blow.’

26

Try as she might, she could not hide her disappointment and frustration at not seeing Harry.

Alice’s mood had changed from those early carefree days in Cairo where she was free to play the field and flirt. Now she had a man she dearly loved and feared losing. Two days later a letter finally arrived from Harry. ‘It has taken 10 days to come, but it is one full of love and all my confidence is renewed.’

27

That same day a convoy of badly wounded soldiers arrived. The men were infested with lice. All had been lying out in the open for between six and eight days, in places where stretcher bearers could not get to them. One soldier had stretched out his hand for a water bottle and his wrist had been immediately cut to pieces by a bullet. ‘One man says the Germans played the machine guns over the wounded. This man was out for five days without food or water. He was at last rescued when the Scottish regiments took the Germans’ front trenches. One man is shot through the bladder and half the perineum shot away. He was rescued by the padre who went out and hauled and pushed and pulled him in.’

28

Another heavy convoy followed early the next day. One soldier had been shot through both legs and was left lying on the battlefield for three days. Then, while his legs were being bandaged, a shell exploded near him, killing the dresser and wounding the soldier in the chest. He was only eighteen, and ‘such a sweet kid’, Alice wrote. ‘The patients are not only very sick, they are mental and nervous. They were most depressed this afternoon so I got in the gramophone which was much enjoyed.’

29

People did not yet understand the causes of what is now termed posttraumatic stress disorder, or how caring for these cases of so-called shell shock affected the nurses themselves. By 16 July the wards were full. Alice worked all day as hard as she could. The next day it was the same. The mood in the wards was grim. She was stunned when a patient punched her. ‘I was doing a dressing. He was very nervous. When I pulled off some wool that was stuck to the hairs of his leg he screamed and turned on me like a rat and with his hard knuckles gave me a terrific punch.’

30

The war had raged now for two years and physical and emotional reserves among the troops were exhausted. Alice understood this, but she was now struggling to maintain her own equilibrium.

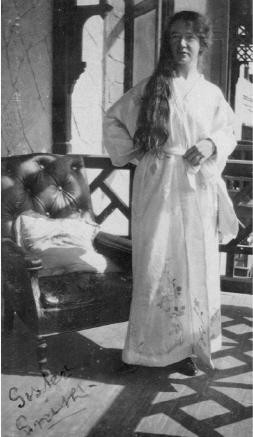

Time away from the demands of the wards was precious. Here, Sister Ada Smith of No.2 Australian General Hospital relaxes in a housecoat on a balcony at Mena House, where the hospital was located. (Photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial P00156.025)

It was common for Australian units to use animals as mascots. Here, a sister at No.3 Australian General Hospital, Abbassia, holds a koala as she stands outside with patients. (Photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial J01714)

With the number of casualties outstripping expectations, the entertainment venue Luna Park was secured for the expansion of No.1 General Hospital. This group of Australian nurses enjoy some respite away from the pandemonium of the overcrowded wards inside. (Photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial C05290)

Despite the circumstances, nursing sisters in Egypt tried to make Christmas Day 1915 special by decorating the mess room. (Photo courtesy of Iain McInnes)

Sister Nell Pike (right) with Sister Ruby Dickinson, who later died of Spanish flu in England. (Photo courtesy of Patricia Williams and Daphne Tongue)

Sister Nell Pike (back row, right) enjoying a dip at Alexandria, 1916. (Photo courtesy of Patricia Williams and Daphne Tongue)