The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs (3 page)

Read The Only Street in Paris: Life on the Rue Des Martyrs Online

Authors: Elaine Sciolino

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #History, #Biography, #Adventure

Acceptance in the “family” comes with privileges but also with a code of conduct: smile and say

bonjour

to every merchant you pass; stop in for a chat even if you’re not buying; never, ever be rude. This means I cannot be rushed. It can take thirty minutes to walk a few hundred feet. I confess there are times when I’m not up for small talk, when I try to avoid the shopkeepers by taking a shortcut through the supermarket. But François the

supermarket security guard knows me now; he always smiles and says

bonjour

.

No matter what the day, I never walk alone on the rue des Martyrs. Somehow, I have made the street mine. I say and do things I wouldn’t dare say and do anywhere else in Paris.

No one, except my two daughters, makes fun of me.

. . .

“It will be dark,” she said.

“No, it has good light,” he said. “When I was here it was getting morning sun.”

“I never imagined living on the

premier étage

.”

—D

IANE

J

OHNSON

,

Le Mariage

I

T TOOK ME A DECADE TO GET TO THE RUE DES MARTYRS.

I discovered the street shortly after my husband, Andy, and I moved to Paris with our two daughters, in 2002. The street became my go-to place on Sunday mornings, when its shops are open while much of Paris is shut tight. In those days, it was a relatively unknown alternative to the tourist-clogged Marais. I called it the “anti-Marais.”

I came to Paris as bureau chief for the

New York Times;

Andy took a job as the only American in a French law firm. We arrived with a plan to go back home after three years, five years max. Then Andy passed the French bar exam. Then we wanted Gabriela, our younger daughter, to finish high school. We stayed on for a sixth year, then a seventh and an eighth.

No longer new expatriates in the first flush of love with France, we became long-term residents with respectable French and mastery of the Paris Métro. Our daughters went off to college in America, and we decided to downsize and leave our sophisticated neighborhood off the rue du Bac, in the Seventh Arrondissement. I wanted the other side of the Seine. I wanted the rue des Martyrs.

In 2010, a year—yes, a year—into the Paris search, an ad for a suspiciously too-good-to-be-true apartment just off the rue des Martyrs popped up on a real estate website. It was on the rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette a few steps from one of the architectural gems of the Ninth Arrondissement, the wheel-shaped place Saint-Georges. The space was good, the rent reasonable. The real estate agent, who worked next door, told us the building even had a fringe benefit that has become a rarity in Paris: a superb concierge.

All of this was demonstrably true. We met the concierge, Ilda Da Costa, and learned that she was Portuguese-born and lived with her husband in a 650-square-foot apartment off the courtyard. They’d raised their three sons there. For more than three decades, she had watched over the building with a combination of intelligence, rigorous attention to detail, and a sense of humor. She was also cool. She wore slim jeans and sneakers and pulled her hair back in a ponytail.

Alas, the apartment was flawed.

Paris is called the “City of Light,” but the dirty little secret is that it is dark most of the year. It is a northern city, on about the same latitude as Seattle. (New York, by contrast, sits on a level with Madrid and Naples.) The apartment was on the

premier étage

: the first floor as the French count it, one floor up in Ameri

can parlance. Living on the

premier étage

meant coexisting with the demons of darkness.

And there was no elevator. That suggested dark corridors, peeling paint, lead pipes, faulty electrical wiring, and unreliable door locks.

The most serious disincentive was the shop on the ground floor just below the apartment. It was called Pyro Folie’s, and it sold fireworks for parties and special-effects material for the stage. Its picture window was decorated with large jars of highly flammable cellulose in a dozen colors.

As a former Washington-based reporter who once wrote about the CIA, I thought I knew a thing or two about uncovering secrets. I launched an investigation of the building. I visited the neighborhood firehouse and the prefecture of police. The police officers and firefighters assured me that they had no records of explosions on file. I interrogated Marie-Ange Roidor, Pyro Folie’s manager, who gave me a look that said, “Who is this crazy American? She’s probably a vegetarian too.”

Celestine Bohlen, my friend and former

New York Times

colleague who lives around the corner, stopped by Pyro Folie’s to follow up. She spoke to a young man working there. “He did his best to reassure,” she told me. “He said, ‘We don’t have a nuclear reactor. We’ve been here thirty-five years. We are grown-ups, sound of mind.’”

Celestine also noted, however, that two rings pierced one of his eyebrows and that he let slip that fireworks are kept in the salesroom on the ground floor (just below the apartment’s master bedroom).

That led me to ask a young French friend to consult her father, an admiral who had once been in charge of France’s Naval Com

mandos. He had decades of experience with explosives and land mines, in countries like Chad and Afghanistan.

“Elaine wants to know whether she should move into an apartment above a fireworks store,” she told him.

He gave her a stern military look and responded with a question: “Would you live on top of a wasp’s nest?”

That should have settled it.

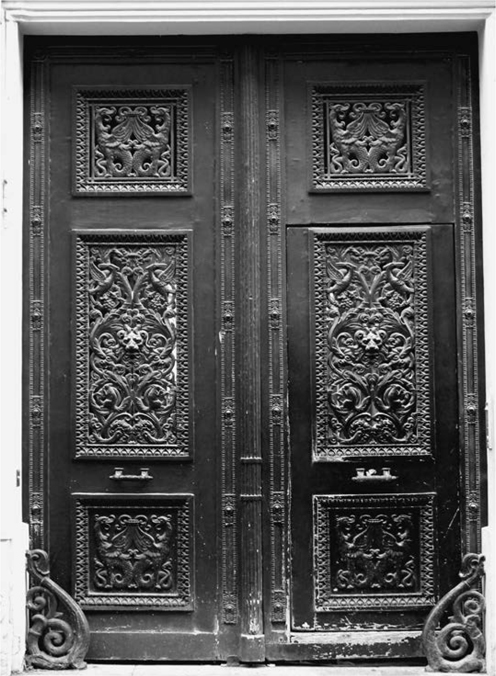

But the outside of the building looked promising. The glossy dark paint on its heavy, wooden outer door had worn away in places, giving it an air of shabby chic. The door had an elaborate wrought-iron

grille

featuring lions, rabbits, birds, and mythical sea monsters. More wrought iron—curved forms over two feet high—anchored each side of the door frame to the ground. Long ago, they had served to protect the building from damage by horse-drawn carriages.

From the moment I stepped into the cobblestoned courtyard, I was no longer thinking about explosions in the middle of the night. I was transported back to the first half of the nineteenth century. There were none of the oversized plastic garbage bins, motorcycles, and bicycles that had cluttered our old building’s courtyard. What were once horse stables had been transformed into automobile garages with discreet black wooden doors.

Then I was escorted into the entryway. Before me was an astonishing architectural feature that I would later learn had been designated as a French historical monument: a wide, curving, oval wooden staircase with a rosewood-and-wrought-iron banister and a gold-trimmed runner in two-toned green. The staircase soared in elegance to an oval beveled-glass skylight that opened up to the sun.

The apartment door opened to reveal twelve-foot-high ceilings. The original doors, mirrors, fireplaces, and ceiling moldings were intact. The designs on the moldings were so intricate that they had names:

denticules,

as in teeth;

palmettes,

as in palm leaves;

marguerites,

as in daisies. Light flooded in through eight-and-a-half-foot-high windows—even sunlight!

I knew we were home.

OUR APARTMENT IS NOT,

strictly speaking, on the rue des Martyrs. But the street’s bounty of merchandise and frenzy of activity are a mere five hundred feet from my front door. I currently count on the rue des Martyrs:

26 restaurants and bistros

3 cabarets and theaters

5 bar-cafés, including a piano bar

5 tea salons

2 supermarkets

13

traiteurs

and take-out shops

6 greengrocers

3 butchers

13 bakeries and pastry shops

2 fish shops

3 cheese shops

5 chocolate shops

4 wine merchants

21 clothing stores

3 secondhand clothing shops

5 jewelers

7 hairdressers

4 skin-care salons

3 pharmacies

5 opticians

2 florists

3 independent bookstores

5 banks

4 real estate agencies

2 hotels

It doesn’t stop there. Add in a church, a high school, a retirement home, a hardware store, a day-care center, a self-service laundry, a recording studio, a mobile phone store. And a locksmith and shoe cobbler, a barometer and gilt frame restorer, a tailor, a musical instrument repairer, and a gay bathhouse called Sauna Mykonos, with a facade like a Greek temple.

Who could ask for anything more?

THE RUE DES MARTYRS STARTS

a block south of the place Saint-Georges, at the dirty back wall of a forlorn church that from this perspective looks like a prison. It moves north, mostly one-way with an uphill angle steep enough to force a walker to slow down. It dead-ends at a cross street that takes you to an even steeper climb straight to the Sacré-Coeur Basilica at the top of Montmartre, the highest point of Paris. The rue des Martyrs can be perceived as two streets—or, better, two worlds—divided by a wide boulevard about three-fourths of the way up. The part below belongs to nineteenth-century commercial and financial

Paris, the part above to what was once the village of Montmartre, outside the city limits.

Immediately, in obedience to my journalistic instincts, I wanted to know everything about my new home, and why the rue des Martyrs has retained the feel of a small village. The street jealously guards its secrets: it has no landmarks, no important architecture, no public gardens, nor any stone plaques on the sides of buildings telling you who was born, lived, worked, or died here. But I didn’t have to go into reporter mode to seek out the experts who could help. They found me.