The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year (14 page)

Read The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year Online

Authors: Linda Raedisch

Tags: #Non-Fiction

The Scandinavian Household Sprite 105

Christmas Tomten figure 1

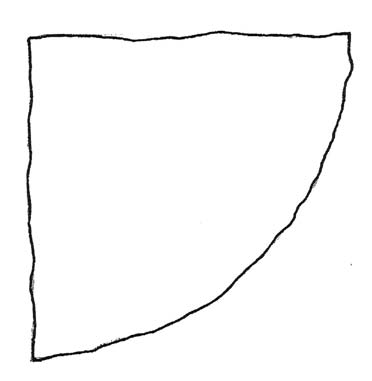

Cut a 41⁄8 inch diameter circle out of your paper. Fold

the circle into quarters and cut along the creases. One quarter equals one hat. Crumple the paper gently to give it

a softer, cloth-like look. (Figure 2) Now roll it into a tall, skinny cone and glue the seam. (Figure 3) Glue the base of the hat to the tomten’s head.

Christmas Tomten figure 2

106 The Scandinavian Household Sprite

Christmas Tomten figure 3

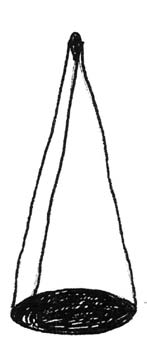

While the glue is drying, cut a 3½ inch length of pipe

cleaner and twist it into a ring. This is the fur trim on your tomten’s cap. Slip it on and secure with a few dabs of glue.

Fold the point of the cap over and glue down.

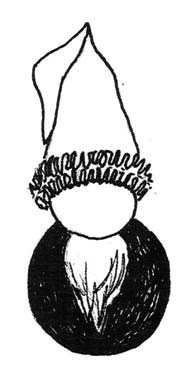

Pull a wisp from the cotton ball and glue on for the

beard. (Figure 4)

Christmas Tomten figure 4

The Scandinavian Household Sprite 107

Recipe: Rice Porridge

The last thing you need on Christmas Eve is a complicated

dish to prepare, so this one is easy. You can even use the leftover rice from the Chinese food you ordered while you

were busy making tomtens. This recipe makes enough for

four humans and one household sprite.

Ingredients:

2 cups cold cooked white rice

2½ cups whole milk

½ cup sugar

½ cup ground almonds

Dash vanilla extract

Dash sherry (optional unless you are cooking for a

Danish nisse in which case you should make it a

generous dash)

Cinnamon

Butter

Combine all ingredients except cinnamon and butter in

a large pot. Stir together and heat to boiling, watching to make sure it doesn’t boil over. Simmer on a low flame for

15 minutes, stirring only occasionally. Pour into a large

bowl or individual dessert dishes and top with cinnamon

and a pat of butter.

So You Want to Buy a Troll

Well, why not? They’re awfully cute these days with their

big feet, bigger noses, beady little eyes and shaggy manes of hair. But before you pick one up at the Christmas market,

you ought to know a little about its ancestry. If the troll and

108 The Scandinavian Household Sprite

the helpful little Scandinavian household sprite are blood relatives, the household sprite certainly never speaks of it, while the troll is barely capable of speech. Scandinavian

trolls, or “goblins” as their name is sometimes translated, do many of the things that elves and fairies do elsewhere: they keep a few cows, pilfer food from the nearby farms and swap their own offspring for human babies.

Because they are not above stealing, many trolls are fab-

ulously rich, though this has done nothing for their looks.

They are governed by a king, but his court in Sweden is

hardly a center of culture. Trolls have few practical skills.

The textile arts are quite beyond them and they have never attempted farming. They can, however, work magic and

have been doing so for as long as anyone can remember.

The trolls are descended from the Norse

jotnar

and

risir

or

“giants” who were present at the world’s beginning, though the giants were both larger and more attractive than their great grandchildren. They also had a bigger role to play in world events, while many of today’s trolls are reduced to

skulking under bridges.

One thing that can be said for the trolls is this: they are excellent timekeepers. There have been several instances in Norway and Iceland where the humans lost count of the

dark days of winter and had to ask the trolls when to cel-

ebrate Christmas. Since trolls are illiterate, they probably used the old Norwegian

primstav,

a sort of farmer’s alma-nac inscribed on a yardstick. Yule was marked by the image of an ornately carved drinking horn. As far as we know, the trolls, like us, have now made the switch from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar.

The Scandinavian Household Sprite 109

The trolls are most likely to be about on Christmas Eve,

perhaps so they can admire one another’s treasure hoards.

This is the one night of the year that humans can take a

peek at the trolls’ subterranean lairs, for the hills rise up on golden pillars to reveal the glittering heaps of chalices, coins and candelabra. The trolls are hoarders

par excellence

, never pawning or selling any of their loot no matter how hard

times get.

Because they’re such terrible cooks, and too stingy to

order in, trolls are always glad of a free meal on Christ-

mas Eve. If you want to prepare dinner for a troll, you must include a generous helping of meat. A few trolls, having

converted to Christianity, promised they would no longer

eat human flesh, but you can hardly expect them to be veg-

etarians. Leave the troll’s meal out in the woods, far from the house; you don’t want him peering in the window when

you open your Christmas presents.

If you decide to take things a step further and install a

troll inside your home, keep him out of the kitchen. He has an aversion to iron, so your stainless steel kitchen implements are sure to put him off. And whatever you do, don’t

put him in the window; the sunlight will either turn him

to stone or cause him to explode. Keep your troll in a dark, out of the way corner and all should be well. If you notice any coins, jewelry or candlesticks going missing, you’ll

know just where to look. If he does explode, don’t expect

your household sprite to clean up the mess. If, however,

your troll accidentally turns to stone, you can always move him to the garden.

Reindeer Games

We know that Santa Claus took his name, if not his char-

acter, from the fourth century St. Nicholas, Bishop of

Myra in Asia Minor. His headquarters, therefore, really

ought to be in Turkey, perhaps among the outbuildings of

some crumbling mountain monastery. There, elves bearded

and hooded like orthodox monks would whittle away by

the light of the beeswax candles, all the while conversing quietly in New Testament Greek. Under the smudged gaze

of the icons, they would keep themselves busy boxing up

batches of Turkish delight to distribute to the world’s children. Or, Santa might have placed his enterprise further

to the east, amid the snows of Mount Ararat, where the

wrecked stalls of Noah’s ark would be put to good use again as workshops and warehouses. What better setting for the

elves as they carve all those toy animals?

If I were to posit a third location for Santa’s workshop,

it would have to be the Federal State of Thuringia in east central Germany.

Das Wütende Heer

, as the Wild Hunt was

111

112 Reindeer Games

known in the snow-covered Thuringian forest, was led by a

white-bearded gentleman named Eckhard. The Hörselberg,

the magical mountain from which the procession issued,

belonged to a goddess referred to in the thirteenth-century

Tannhäuser

legend as Venus, Roman goddess of love, but who might originally have been Freya, one of the Vanir, or Norse fertility gods. The errand on which Eckhard and his

troop were bound was a trip around the world, an excur-

sion which took them only five hours. Unfortunately, no

sleigh is mentioned in relation to Eckhard, only a black

horse and a staff. And since the Hörselberg, a. k. a. “Venus-berg,” was the scene of fertility-inducing sexual license, the elves would probably have been making the wrong sort of

toys.

Like St. Martin’s Land, Santa’s realm is necessarily one

of the imagination, and for various reasons, the Arctic

serves as the most magical blueprint for this never-to-be-

discovered country. But before we can explore the rea-

sons why, we must explore a name. Lapland, which lies well within the frozen embrace of the Arctic Circle, is so called because it is the home of the Lapps, a non-Germanic Scandinavian people who have been there for as long as any-

one can remember.24 Although they share certain aspects

of their culture with the peoples of Siberia, their language is most closely related to Finnish. The term “Lapp” is so old 24. Because of their stature, smaller than that of their Russian or Germanic neighbors, and because of their apparently remarkable cranial measurements—early twentieth- century anthro-

pologists were wild for cranial measurements—the Lapps, like Gardner’s pixyish Picts, have also been put forward as the original elves.

Reindeer Games 113

that its etymology is uncertain. One theory is that “Lapp”

meant “patch of cloth:” not such a strong indictment, especial y given that it may simply refer to the use of appliqué in their traditional woolen garments. Then again, it may

come from a Finnish word meaning “people who live at the

edge of the world.” The Norwegians referred to them not

as Lapps but as “Finns on skis.” Either way, the preferred term is now Sami25, which is what the Sami have been cal -

ing themselves all along, so that is the term I will use.

When it comes to their homeland, I am going to stick

with “Lapland,” because, at least for us non-Sami, “Lap-

land” says Christmas magic far better than the more correct

Sapmi

. Lapland’s reputation as a magical place inhabited by a magical people probably goes all the way back to the first encounters between Norsemen and Sami. Even before the

divisive advent of Christianity, the Sami differed from their Nordic neighbors both culturally and spiritually. While

their southern neighbors were able to scratch out a few

farms from the deciduous forests and the steep banks of the fjords, the Sami’s arctic environment dictated nomadism.

Our word “tundra” comes from Sami. During the blink-

of-an-eye summer, the surface of the tundra turns into a

spongy, insect-ridden bog. The rest of the year, it is covered in ice and snow. And while the mountains of Lapland are

picturesque, they are impossible to farm. The only crop the Sami could depend on was lichen, the reindeer’s mainstay.

For the Sami, the spirits of the mountains and bogs

were always close at hand. The Sami gods were visible in

such naturally occurring idols as an oddly-shaped boulder

25. You will also find it spelled “Same” and “Saami.”

114 Reindeer Games

or birch snag, and they were audible through the medium

of the reindeer skin drum. In both the pagan and the early Christian eras, the Norsemen, whose native religion was

shamanic to a somewhat lesser degree, often employed the

Sami as consultants in times of supernatural need. With the help of the drum, the

noide

, or Sami shaman, allowed his spirit to fare forth from his body, enabling it to spy on people and find lost objects in places as far away as Iceland.