The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (9 page)

If you think about it, the very nature of the iamb means that if this additional trick were disallowed to the poet then

all

iambic verse would have to terminate in a stressed syllable, a masculine ending…

If winter comes can spring be far behind?

…would be possible, but

A thing of beauty is a joy for ev(er)

…would not. Keats would have had to find a monosyllabic word meaning ‘ever’ and he would have ended up with something that sounded Scottish, archaic, fey or precious even in his own day (the early nineteenth century).

A thing of beauty is a joy for ay.

Words like ‘excitement’, ‘little’, ‘hoping’, ‘question’, ‘idle’, ‘widest’ or ‘wonder’ could

never

be used to close an iambic line. That would be a ridiculous restriction in English. How absurdly limiting not to be able to end with an -ing, or an -er or a -ly or a -tion or any of the myriad weak endings that naturally occur in our language.

B

UT THERE IS MORE TO IT THAN THAT

. A huge element of all art is constructed in the form of

question

and

answer

. The word for this is

dialectic

. In music we are very familiar with this call-and-response structure. The opening figure of Beethoven’s Fifth is a famous example:

Da-da-da-Dah

Da-da-da-Derr

Beethoven actually went so far as to write the following in the score of the Finale of his String Quartet in F major:

Muss es sein?

Must it be?

Es muss sein!

It must be!

In poetry this is a familiar structure:

Q: Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

A: Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

It is common in rhetoric too.

Ask not what your country can do for you

But what you can do for your country.

This is a deep, instinctive property of so much human communication. In the Greek drama and dance it was called

strophe

and

antistrophe

, in the liturgy of the Church it is known as

versicle

and

response

.

One might suggest that this is something to do with the in-and-out pumping of the heart itself (

systole

and

diastole

) and the very breath of life (

inhalation

and

exhalation

). Yin and yang and other binary oppositions in thought and the natural world come to mind. We also reason dialectically, from problem to solution, from proposition to conclusion, from

if

to

then

. It is the copulation of utterance: the means by which thought and expression mimic creation by taking one thing (

thesis

), suggesting another (

antithesis

) and making something new of the coupling (

synthesis

), prosecution, defence, verdict.

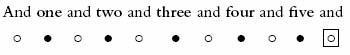

The most obvious example of a poem with an

if then

then

structure is of course Kipling’s poem ‘If’, regularly voted ‘the nation’s favourite’. It is written in strict iambic pentameter, but with alternating feminine and masculine line endings throughout. He does this with absolute regularity throughout the poem: switching between lines of weak (eleven syllable) and strong (ten syllable) endings, which gives a characteristic swing to the verse. Try reading out loud each

stanza

(or verse) below, exaggerating the

tenth

syllable in each line as you read, tapping the table (or your thigh) and really emphasising the last beat. Do you see how this metrical alternation precisely suggests a kind of dialectical structure?

If you can keep your head when all a

bout

you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on

you

,

If you can trust yourself when all men

doubt

you

But make allowance for their doubting

too

,

If you can dream–and not make dreams your

mas

ter,

If you can think–and not make thoughts your

aim

;

If you can meet with Triumph and Dis

ast

er

And meet those two impostors just the

same

;

And meet those two impostors just the

same

;

If you can fill the unforgiving

min

ute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance

run

,

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s

in

it,

And–which is more–you’ll be a Man, my

son

!

What’s actually happening is that the wider line structures echo the metrical structure: just as the

feet

go weak-

strong

, so the lines go weak-

strong

.

You might put the thought into iambic pentameters:

The weaker ending forms a kind of question

The stronger ending gives you your reply.

The finality of downstroke achieved by a strong ending seems to answer the lightness of a weak one. After all, the most famous weak ending there is just happens to be the very word ‘question’ itself…

To be, or not to be: that is the question.

It is not a rule, the very phrase ‘question-and-answer’ is only an approximation of what we mean by ‘dialectic’ and, naturally, there is a great deal more to it than I have suggested. Through French poetry we have inherited a long tradition of alternating strong-weak line endings, which we will come to when we look at verse forms and rhyme. The point I am anxious to make, however, is that metre is more than just a ti-

tum

ti-

tum

: its very regularity and the consequent variations available within it can yield a structure that

EXPRESSES MEANING QUITE AS MUCH AS THE WORDS THEMSELVES DO

.

Which is not to say that eleven syllable lines

only

offer questions: sometimes they are simply a variation available to the poet and result in no particular extra meaning or effect. Kipling does demonstrate though, in his hoary old favourite, that when used deliberately and regularly, alternate measures can do more. The metrist Timothy Steele

12

has pointed out how Shakespeare, in his twentieth sonnet ‘A woman’s face, with Nature’s own hand painted’ uses

only

weak endings throughout the poem: every line is eleven syllables. Shakespeare’s

conceit

in the poem (his image, or overarching concept) is that his beloved, a boy, has all the feminine graces. The proliferation of feminine endings is therefore a kind of metrical pun.

Macbeth’s ‘Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow’ is another celebrated example of iambic pentameter ending with that extra or

hypermetrical

unstressed syllable. Note, incidentally, that while you would not normally choose to emphasise a word like ‘and’ in a line of poetry, the beauty of Shakespeare’s iambs here is that the rhythm calls for the actor playing Macbeth to hit those ‘ands’ harder than one would in a line like:

I want some jam and tea and toast today

With Shakespeare’s line…

To

mor

row

and

to

mor

row

and

to

mor

row

…the futility and tedium of the succession of tomorrows is all the more manifest because of the metrical position of those ‘ands’. Which of us hasn’t stressed them in sentences like ‘I’ve got to mow the lawn

and

pick up the kids from school

and

do the tax returns

and

write a thank you letter

and

cancel the theatre tickets

and

ring the office…’?

An eleven-syllable line was more the rule than the exception in Italian poetry, for the obvious reason that an iambic hendecasyllabic line must have a

weak

ending, like-a almost-a ever-y word-a in Italian-o. Dante’s

Inferno

is written in iambic

endecasíllabo

.

Nel

mez

zo

del

camm

in

di

nost

ra

vit

a

An English translation might go, in iambic pentameter:

Mid

way

up

on

the

journ

ey

through

our

life

There would be no special reason to use hendecasyllables in translating the

Inferno

: in fact, it would be rather difficult. English, unlike Italian, is full of words that end with a stressed syllable. The very nature of the iamb is its light-heavy progression, it seems to be a deeply embedded feature of English utterance: to throw that away in the pursuit of imitating the metrics of another language would be foolish.

Lots of food for thought there, much of it beyond the scope of this book. The point is that the eleven-syllable line is open to you in

your

iambic verse.

Why not

nine

syllables, you may be thinking? Why not

dock

a syllable and have a nine-syllable line with a weak ending?

Let’s

sit

our

selves

be

side

this

riv

er

Well, this docking, this

catalexis

, results in an iambic

tetrameter

(four accents to a line) with a weak ending, that extra syllable. The point about pentameter is that it must have

five

stresses in it. The above example has only

four

, hence

tetra

meter (pronounced, incidentally, tetr

A

meter, as pentameter is pent

A

meter).

Writers of iambic pentameter always

add

an unstressed syllable to make eleven syllables with five beats, they don’t take off a strong one to make four. They must keep that count of five. If you choose iambic pentameter you stick to it. The heroic line, the five-beat line, speaks in a very particular way, just as a waltz has an entirely different quality from a polka. A four-beat line, a tetrameter, has its individual characteristics too as we shall soon see, but it is rare to mix them up in the same poem. It is no more a

rule

than it is a rule never to use oil paints and watercolours in the same picture, but you

really have to know what you’re doing

if you decide to try it. For the purposes of these early exercises, we’ll stay purely pentametric.

Here are a few examples of hendecasyllabic iambic pentameter, quoting some of the same poets and poems we quoted before. They all go:

O

UT WITH YOUR PENCIL AND MARK THEM UP:

don’t forget to

SAY THEM OUT LOUD

to yourself to become familiar with the

effect

of the weak ending.

So priketh hem nature in hir corages;

Than longen folk to goon on pilgrimages

13

C

HAUCER:

The Canterbury Tales

, General Prologue

A woman’s face with Nature’s own hand painted

Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion;

S

HAKESPEARE:

Sonnet 20

That thou shall see the diff’rence of our spirits,

I pardon thee thy life before thou ask it:

S

HAKESPEARE:

The Merchant of Venice

, Act IV, Scene 1