The Night Fairy (3 page)

Authors: Laura Amy Schlitz

T

T

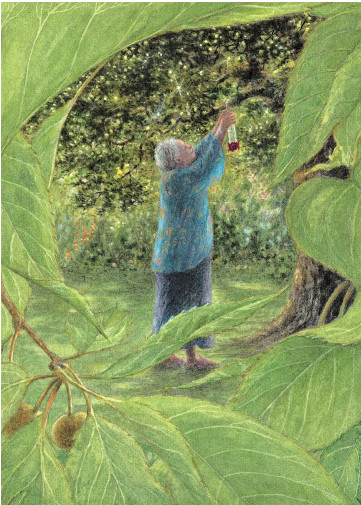

hree days after Flory saw the hummingbird, the giantess hung another tube from the oak tree.

Flory squinted. It was almost sunset and she was looking west, but she could see that the new tube was filled with liquid, not seeds. The bottom of the tube had red metal daisies on it. Flory thought this queer: daisies are white, not red, and no flower is made of metal. She cupped her hands around her mouth.

“Skug! Skug! Skuggle!”

The boughs of the thorn apple trembled. Down the tree came Skuggle, lashing his tail with excitement. He spurted over the grass, surged up the cherry tree, and arrived at Flory’s side in a rush that made her feather tip shake.

“Is there something to eat?”

Flory pointed to the tube. “I don’t know. The giantess put that out, but I don’t know what’s in it.”

Skuggle scratched behind his ear. “Oh, that. She put that out last year. It’s mostly water.” He looked down at his claw, saw that there was a flea clinging to the tip, and poked the flea into his mouth. “I got on it last year. It’s a little slippery, but I can catch hold. The only thing is, it’s not worth the trouble. It’s just water and some sweet.”

“I can’t think why she puts out those things.”

“That’s easy.” Skuggle scratched his other ear. “She wants to eat us. She puts food out so we’ll come for it. Then she can kill us.”

“Yes, but she never does kill us.”

Skuggle bobbed his head, agreeing. “That’s because we’re too quick for her. But if we didn’t run away, she would eat us.”

“She must be a great fool.”

“Oh, yes,” agreed Skuggle. “Only Chickadee says —” He snatched a ripe cherry off the tree and crammed it into his mouth.

“What does the chickadee say?” asked Flory. She had noticed that the chickadee was one of the boldest birds in the yard. He sometimes ate from the seed tube when the giantess was sitting on the patio.

“Chickadee says she doesn’t hate us. Chickadee says the giantess puts out seed because she likes us. But Chickadee is wrong, because the giantess eats birds. Big birds. I’ve seen the bones in the garbage.”

Flory wrinkled her nose. Before she had lived near giants, she hadn’t known about garbage. The giantess kept a big green can of it in the yard. Raccoons sometimes broke in at night and strewed the garbage over the lawn. Skuggle knew better than to fight the raccoons for something to eat — they were much bigger and stronger than he was — but he feasted on garbage the following mornings, when the raccoons slept. He always smelled awful after eating garbage. Flory tried to shame him by pinching her nostrils shut and looking prim, but Skuggle didn’t care. It was almost impossible to make Skuggle feel bad when his stomach was full.

“You should keep away from that garbage,” Flory warned him. “Last time you ate yourself sick.”

“Oh, dear, yes,” sighed Skuggle, “how good that was!” He glanced back at the water tube. “Why do you want to know about that tube? That’s not for us. It’s for hummingbirds. They like to suck on the fake flowers.”

“Do they?” asked Flory. “In that case, I want to go there — to the oak tree.”

“I thought you didn’t like that tree late in the day. There’s bats in that tree,” Skuggle reminded her. “You’re frightened of bats.”

Flory knew it. A colony of bats nestled in the hollow at the top of the tree. Often she heard them squeaking in the garden after dark. She stuffed her ears with cobwebs in order to block out the sound, but she had bad dreams all the same. “The bats won’t be out till dusk,” she said. “Anyway, I’m not frightened of them. I just happen to hate them. It’s not the same thing.”

Skuggle looked sly. “You hate them because you’re afraid of them,” he said. He lowered his voice and sang a little song. “Fraidy-cat,” he sang softly. “Fraidy-cat! Flory-dory fraidy-cat!”

“If you don’t stop that, I’ll sting you,” Flory said coldly.

Skuggle shut his mouth and looked meek.

“Turn around so I can climb on your tail. I want to go to the oak tree.”

“Why?” demanded Skuggle.

“So that I can talk to the hummingbirds. Take me there now, and I’ll spear some suet for you later.”

“Why don’t you give it to me now?”

“Because I won’t. I’ll feed you later, but not now.”

Skuggle turned his tail in her direction. “I don’t see what you want with hummingbirds. They’re nasty birds,” he warned her. “I went to rob a nest once, and the mother nearly pecked my eye out. And the eggs were tiny,” he added petulantly. “Not much bigger than peas. Hardly worth eating.”

Flory paid no attention. She climbed onto the squirrel’s tail and waited for him to flick her onto his ear. In another moment, Skuggle leaped from the cherry tree to the oak tree. He stopped by the tube with the metal flowers. Flory slid off. “You can go now,” she said, and Skuggle dashed off again.

Flory waited for a long time. As she waited, she imagined the hummingbird again: the magic of his feathers in the light, the rapid double circles he made with his wings. She tried to imagine what it must be like to fly with wings like that. She lifted her arms, muscles tight, and fluttered the edges of her fingers. She imagined wings quivering, drumming on the air.

All at once the drumming sound was real. The hummingbird hovered beside the water tube. He was so close that Flory could feel the wind of his flight. His feathers rippled like green water; his wings were shadow and speed. “Hummingbird!” cried Flory. “I want you!”

The hummingbird dug his beak into the metal flower. After sucking at the water tube, he darted backward and rose straight into the air. He did not pay one bit of attention to Flory.

“Hummingbird, come back!” shouted Flory.

But he did not come back until he was thirsty again. Flory began to visit the feeder every day, waiting for him to appear. She soon found out that there were four hummingbirds that used the feeder: three males and a female. They drank the sugar water fiercely, as if they had a raging thirst. They were fierce, too, in the way they fought over the feeder, stabbing with their sharp beaks like swordsmen. Flory liked their fierceness. She would not have liked them half as much if they had been tame. She liked the males best, because of the ruby-colored patch on their throats, but she would have happily taken a female bird for her mount. Male or female, the hummingbirds had one thing in common: they ignored Flory as if she were invisible. Again and again she called out to them. Not one of them bothered to look her way.

“Nasty things,” Flory said, echoing Skuggle. But she didn’t mean it. She still wanted a hummingbird of her own — wanted one dreadfully — and when she dreamed at night, it was of sitting astride that jewel-green back, floating over a wilderness of flowers.

M

M

idsummer came, a season of blinding-hot days and evening thunderstorms. Flory disliked the heat of the sun, but she enjoyed the storms, especially when they came at night. She liked to think of the bats getting wet.

Flory was growing up. She was as tall as two acorns now, and her curls brushed her shoulders. She could climb as nimbly as an insect, and leap from twig to twig as recklessly as Skuggle himself. Her little house was full of things she had made: a lily-leaf hammock, a quilt of woven grass, and a score of airy gowns crafted from poppies and rose petals. She had food saved for the winter: a mound of sunflower seeds and three snapdragon flowers stuffed with pollen.

She spent a week harvesting cherries, hacking them apart with her dagger, cutting out the pits, and drying them with a magic spell. Every day she learned new spells. They came into her head like songs.

She was half-asleep beside the hummingbird feeder one afternoon when she heard a blue jay squawking. At first she ignored him, because she knew how much blue jays enjoy making noise. They like to take a scrap of song or a piece of news and repeat it over and over, just for the thrill of screaming. But though they shriek for the fun of it, they often tell the truth about what is going on. And this blue jay was shrieking “hummingbird” and “spiderweb” and “trapped!”

Flory sat bolt upright. She peered around the garden without seeing either the hummingbird or the spiderweb. She opened her mouth to shout for Skuggle, and then shut it. Skuggle had been known to eat baby birds. If the hummingbird was caught in a spiderweb, Skuggle might eat him.

An idea took shape in her mind. She shut her eyes and pressed the palms of her hands against her eyelids. She half hissed, half prayed, “Let me see the hummingbird!”

It was a new magic, one she had never tried. At first she saw only the reddish glow of her inner eyelids. Then she saw the spiderweb. It belonged to the black-and-yellow spider that patrolled the juniper bush by the side gate. The sticky threads had snared the hummingbird’s wings. The more the bird struggled, the more it was held fast.

“I’ll come,” Flory said breathlessly. “Don’t be afraid, hummingbird! I’ll save you!”

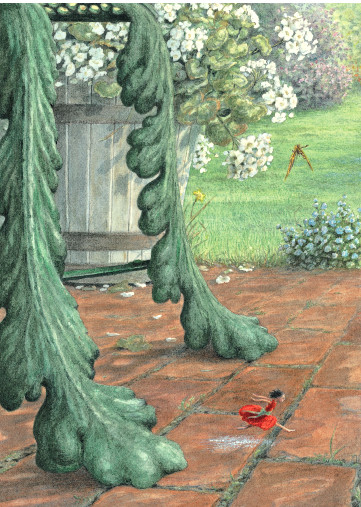

She looked down, saw a twig below her, and leaped for it. Once she caught hold, she looked below for another. It was a haphazard, dangerous way to get to the ground, but she had no time to waste. She flung herself from twig to twig until she reached the bottom branch. Then she shinnied down the trunk.

Blades of grass rustled like cornstalks over her head. Flory wished she had thought to bring her dagger so that she could cut her way through the tangles. The idea crossed her mind that she had no idea how she was going to save the bird. Still, she had her magic, and her mind was made up. It would have to be enough.

She thrashed through the grass, breaking into a run when she came to the open space of the patio. By the time she reached the side gate, she was out of breath. She saw the spiderweb above her — a great silver network covering most of the juniper bush. The trapped bird was less than a foot from the ground.

“I’m coming!” shouted Flory. “Don’t be frightened! I’m coming to save you, hummingbird!”

Once the words were out, she clapped her hand over her mouth. Web-building spiders do not stray far from their webs: the spider must be close at hand. But by a stroke of good luck, the spider was nowhere to be seen. Perhaps she was busy with other prey. All the same, she might return at any moment.

Flory jumped straight up into the air, catching the bottom branch of the juniper bush. She swung back and forth until she hooked her legs over the branch. “I’ve come to set you free,” she said breathlessly. “I’m going to pull the web off you. Only you must promise me something first.”

The hummingbird twisted its head to look at her. The feathers under its chin were pearly white. It was a female.

“I’ve seen you,” said Flory. “You come to the water feeder.”

“I’ve never seen

you,

” said the hummingbird. She craned her head for another look. “Why are you awake? You’re a night fairy.”

“I used to be a night fairy,” Flory said. “Now I’m not. Will you promise?”

“Promise?” asked the hummingbird.

“Yes,” said Flory. She felt her cheeks grow warm; she was not often ashamed, but she felt a little awkward about what she was going to say. She took a deep breath and spoke very clearly so that she wouldn’t have to say it twice. “I’ll set you free, but after I set you free, you must be my very own hummingbird and let me ride on your back.”

She waited for the hummingbird to agree, but the hummingbird was still. The glittering wings were motionless. When they didn’t catch the light, they were plain gray. Flory gave a nervous little laugh.

“No,” said the hummingbird.

“No?” echoed Flory.

“No,” said the hummingbird. “I won’t belong to you. I belong to myself. And I have eggs.” A note of pride came into her voice. “If I get free, I shall have to look after my nestlings. I shan’t have time to bother with you.”

Flory could not think what to say next. She reached upward, pulling herself closer to the bird. “But I

want

to cut you free,” she said. “I’d like to. If you don’t get free, you’ll die.”

The hummingbird’s throat moved. Her beak was open; she was panting for breath. “If I die, the eggs will die,” she said hoarsely. “Night will fall, and it will be cold — and the chicks will die inside the shells.”

Flory felt a funny ache in her throat. She was not the kind of fairy who cried easily, and she didn’t think the hummingbird cried at all. But the words “the chicks will die” made her feel queer, as if her heart were swollen and sore. She gave herself a little shake, trying to replace the queer feeling with crossness. “It’s your own fault,” she said. “I’m perfectly willing to set you free. All you have to do is promise to be mine. Then you can warm the eggs, and the chicks won’t die.”

“I can’t promise,” said the hummingbird.

“Why not?” demanded Flory.

“Because I can’t lie. Hummingbirds don’t.”

Flory inched closer. “I wouldn’t make you serve me all the time,” she coaxed. “Only sometimes. I want to ride on your back.”

“It doesn’t matter what you want,” said the hummingbird in her low, scratchy voice. “I can’t think about that. My eggs are growing cold.”

Flory glowered at the hummingbird. All at once, she wanted to burst into tears. She wanted to stamp her feet and shout and kick. She realized that she was going to free the hummingbird and get nothing in return.

“Hold still,” she said furiously. “I’m going to set you free. You don’t deserve it, but I’m going to help.”

She yanked one of the strands in the web. But the web would not break. Instead, it stretched. When Flory tried to jerk away, the sticky silk glued itself to her forearm.

“You’ll get caught yourself,” said the hummingbird.

Flory could see that this was a real danger. All the same, she wasn’t going to give up. She thought for a moment. “I could cut you loose if I had my dagger,” she said. “I have one up in the cherry tree. It’s sharp. If you’ll wait till I fetch it —”

“No,” said the hummingbird. “Listen to me. There may not be time to save me — the spider will poison me soon — but if you would go to my nest and warm the eggs —”

Flory caught her breath. “I could do that!” she exclaimed. “If you tell me where the nest is, I’ll go and warm the eggs — and they

won’t

die! — and then I’ll come back with my dagger and save you.”

“Will you?” Something gleamed in the hummingbird’s eye. Her throat moved in and out. “Will you save my nestlings?”

“I will,” Flory promised. “Tell me where your nest is.”

The hummingbird twisted her head, staring hard into Flory’s face.

“It’s all right,” Flory told her. “I don’t eat eggs. Ugh.”

“I built my nest between the fence post and the wall,” whispered the hummingbird, “the fence post close to the fishpond. It’s hidden by the barberry bush. You’ll have to climb the barberry bush to get to it.”

Flory nodded briskly. “I can do that,” she said, though she knew how prickly barberry bushes were, and she feared the climb. “Don’t worry. I’ll find the nest and warm the eggs. And then I’ll come back.”

She yanked her arm away from the spiderweb. The sticky thread left a red welt on her arm. Flory was not going to fuss over a minor wound like that. She set her teeth, turned her back on the hummingbird, and set forth on her quest.