The New Penguin History of the World (83 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

These changes provoke a sense of culmination and climax. They matured only shortly before Islam arrived in the subcontinent, but early enough for a philosophical outlook to have solidified, one which has marked India ever since and has shown astonishing invulnerability to competing views. At its heart was a vision of endless cycles of creation and reabsorption into the divine, a picture of the cosmos which predicated a cyclic and not a linear history. What difference this made to the way Indians have actually behaved – right down to the present day – is a huge subject, and almost impossible to grasp. It might be expected to lead to passivity and scepticism about the value of practical action, yet this is very debatable. Few Christians live lives wholly coherent with their beliefs and there is no reason to expect Hindus to be more consistent. The practical activity of sacrifice and propitiation in Indian temples survives still. Yet the direction of a whole culture may none the less be determined by the emphasis of its distinctive modes of thought and it is difficult not to feel that much of India’s history has been determined by a world outlook which stressed the limits rather than the potential of human action.

For the background to Islam in India we have to return to 500 or so. From about that time, northern India was once again divided in obedience both to the centrifugal tendencies which afflicted early empires and to the appearance of a mysterious invasion of ‘Hunas’. Were they perhaps Huns? Certainly they behaved like them, devastating much of the north-west,

sweeping away many of the established ruling families. Across the mountains, in Afghanistan, they mortally wounded Buddhism, which had been strongly established there. In the subcontinent itself, this anarchic period did less fundamental damage. Though the northern plains had broken up again into warring kingdoms, Indian cities do not seem to have been much disturbed and peasant life recovers quickly from all but the worst blows. Indian warfare appears rapidly to have acquired important and effective conventional limits on its potential for destructiveness. The state of affairs over much of the north at this time seems in some ways rather like that of some European countries during the more anarchic periods of the Middle Ages, when feudal relationships more or less kept the peace between potentially competitive grandees but could not completely contain outbreaks of violence which were essentially about different forms of tribute.

Meanwhile, Islam had come to India. It did so first through Arab traders on the western coasts. Then, in 712 or thereabouts, Arab armies conquered Sind. They got no further, gradually settled down and ceased to trouble the Indian peoples. A period of calm followed which lasted until a Ghaznavid ruler broke deep into India early in the eleventh century with raids which were destructive, but again did not produce radical change. Indian religious life for another two centuries moved still to its own rhythms, the most striking changes being the decline of Buddhism and the rise of Tantrism, a semi-magical and superstitious growth of practices promising access to holiness by charms and ritual. Cults centred on popular festivals at temples also prospered, no doubt in the absence of a strong political focus in post-Gupta times. Then came a new invasion of central Asians.

These invaders were Muslims and were drawn from the complex of Turkish peoples. Theirs was a different sort of Islamic onslaught from earlier ones, for they came to stay, not just to raid. They first established themselves in the Punjab in the eleventh century and then launched a second wave of invasions at the end of the twelfth century, which led within a few decades to the establishment of Turkish sultans at Delhi, who ruled the whole of the Ganges valley. Their empire was not monolithic. Hindu kingdoms survived within it on a tributary basis, as Christian kingdoms survived to be tributaries of Mongols in the West. The Muslim rulers, perhaps careful of their material interests, did not always support their co-religionists of the

Ulema

who sought to proselytize, and were willing to persecute (as the destruction of Hindu temples shows).

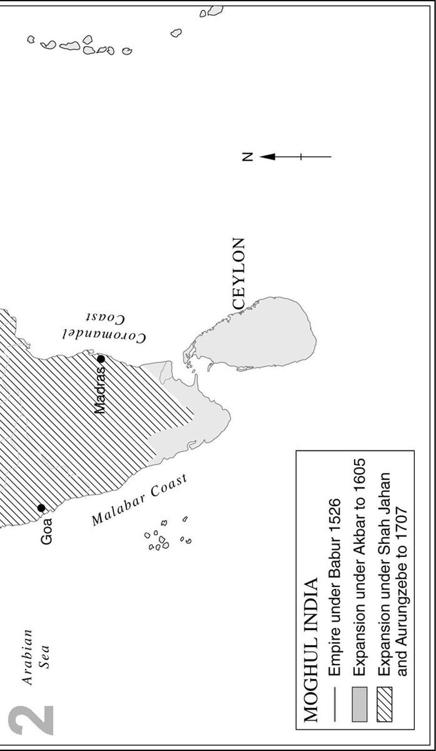

The heartland of the first Muslim empire in India was the Ganges Valley. The invaders rapidly overran Bengal and later established themselves on the west coast of India and the tableland of the Deccan. Further south they did not penetrate and Hindu society survived there largely unchanged.

In any case, their rule was not to last long even in the north. In 1398 Timur Lang’s army sacked Delhi after a devastating approach march which was made all the speedier, said one chronicler, because of the Mongols’ desire to escape from the stench of decay arising from the piles of corpses they left in their wake. In the troubled waters after this disaster, generals and local potentates struck out for themselves and Islamic India fragmented again. None the less, Islam was by now established in the subcontinent, the greatest challenge yet seen to India’s assimilative powers, for its active, prophetic, revelatory style was wholly antithetical both to Hinduism and to Buddhism (though Islam, too, was to be subtly changed by them).

New Sultans emerged at Delhi but showed no power to restore the former Islamic empire. Only in the sixteenth century was it revived by a prince from outside, Babur of Kabul. On his father’s side he descended from Timur and on his mother’s from Chinghis, formidable advantages and a source of inspiration to a young man schooled in adversity. He quickly discovered he had to fight for his inheritance and there can have been few monarchs who, like Babur, conquered a city of the importance of Samarkand at the age of fourteen (albeit to lose it again almost at once). Even when legend and anecdote are separated, he remains, in spite of cruelty and duplicity, one of the most attractive figures among great rulers: munificent, hardy, courageous, intelligent and sensitive. He left a remarkable autobiography, written from notes made throughout his life, which was to be treasured by his descendants as a source of inspiration and guidance. It displays a ruler who did not think of himself as Mongol in culture, but Turkish in the tradition of those peoples long settled in the former eastern provinces of the Abbasid caliphate. His taste and culture were formed by the inheritance of the Timurid princes of Persia; his love of gardening and poetry came from that country and fitted easily into the setting of an Islamic India whose courts were already much influenced by Persian models. Babur was a bibliophile, another Timurid trait; it is reported that when he took Lahore he went at once to his defeated adversary’s library to choose texts from it to send as gifts to his sons. He himself wrote, among other things, a forty-page account of his conquests in Hindustan, noting its customs and caste structure and, even more minutely, its wildlife and flowers.

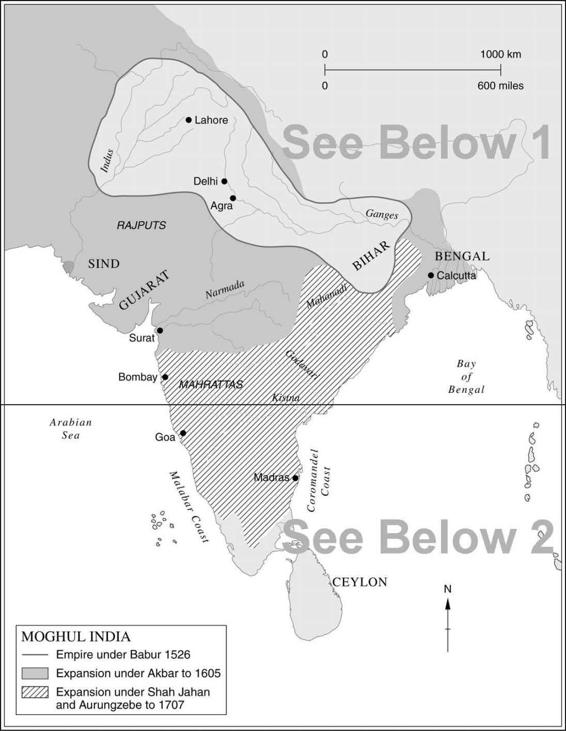

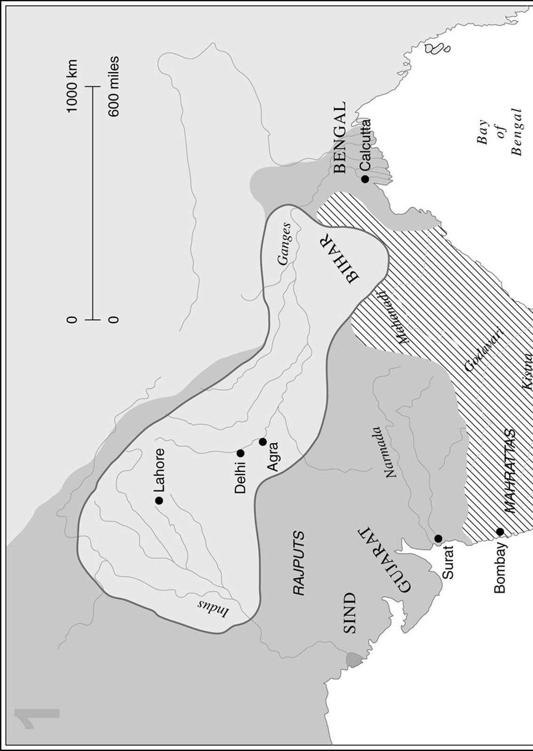

This young prince was called in to India by Afghan chiefs, but had his own claims to make to the inheritance of the Timurid line in Hindustan. This was to prove the beginning of Moghul India; Moghul was the Persian word for Mongol, though it was not a word Babur applied to himself. Originally, those whose discontent and intrigue called him forward had only aroused in him the ambition of conquering the Punjab, but he was

soon drawn further. In 1526 he took Delhi after the Sultan had fallen in battle. Soon Babur was subduing those who had invited him to come to India, while at the same time conquering the infidel Hindu princes who had seized an opportunity to renew their own independence. The result was an empire which in 1530, the year of his death, stretched from Kabul to the borders of Bihar. Babur’s body, significantly, was taken as he directed to Kabul, where it was buried in his favourite garden with no roof over his tomb, in the place he had always thought of as home.

The reign of Babur’s son, troubled by his own instability and inadequacy and by the presence of half-brothers anxious to exploit the Timurid tradition which, like the Frankish, prescribed the division of a royal inheritance, showed that the security and consolidation of Babur’s realm could not be taken for granted. For five years of his reign, he was driven from Delhi, though he returned there to die in 1555. His heir, Akbar, born during his father’s distressed wanderings (but enjoying the advantages of a very auspicious horoscope and the absence of rival brothers), thus came to the throne as a boy. He inherited at first only a small part of his grandfather’s domains, but was to build from them an empire recalling that of Asoka, winning the awed respect of Europeans, who called him ‘the Great Moghul’.

Akbar had many kingly qualities. He was brave to the point of folly – his most obvious weakness was that he was headstrong – enjoying as a boy riding his own fighting elephants and preferring hunting and hawking to lessons (one consequence was that, uniquely in Babur’s line, he was almost illiterate). He once killed a tiger with his sword in single combat and was proud of his marksmanship with a gun (Babur had introduced firearms to the Moghul army). Yet he was also, like his predecessors, an admirer of learning and all things beautiful. He collected books and in his reign Moghul architecture and painting came to their peak, a department of court painters being maintained at his expense. Above all, he was statesmanlike in his handling of the problems posed by religious difference among his subjects.

Akbar reigned for almost half a century, until 1605, thus just overlapping at each end the reign of his contemporary, Queen Elizabeth I of England. Among his first acts on reaching maturity was to marry a Rajput princess who was, of course, a Hindu. Marriage always played an important part in Akbar’s diplomacy and strategy, and this lady (the mother of the next emperor) was the daughter of the greatest of the Rajput kings and therefore an important catch. None the less, something more than policy may be seen in the marriage. Akbar had already permitted the Hindu ladies of his harem to practise the rites of their own religion within it, an unprecedented act for a Muslim ruler. Before long, he abolished the poll tax on non-Muslims; he was going to be the emperor of all religions, not a Muslim fanatic. Akbar even went on to listen to Christian teachers; he invited the Portuguese who had appeared on the west coast to send missionaries learned in their faith to his court and three Jesuits duly arrived there in 1580. They disputed vigorously with Muslim divines before the emperor and received many marks of his favour, though they were disappointed in their long-indulged hope of his conversion. He seems, in fact, to have been

a man of genuine religious feeling and eclectic mind; he went so far as to try to institute a new religion of his own, a sort of mishmash of Zoroastrianism, Islam and Hinduism. It had little success except among prudent courtiers and offended some.

However this is interpreted, it is evident that the appeasement of non-Muslims would ease the problems of government in India. Babur’s advice in his memoirs to conciliate defeated enemies pointed in this direction too, for Akbar launched himself on a career of conquest and added many new Hindu territories to his empire. He rebuilt the unity of northern India from Gujarat to Bengal and began the conquest of the Deccan. The empire was governed by a system of administration much of which lasted well into the era of the British Raj, though Akbar was less an innovator in government than the confirmer and establisher of institutions he inherited. Officials ruled in the emperor’s name and at his pleasure, they had the primary function of providing soldiers as needed and raising the land tax, now reassessed on an empire-wide and more flexible system devised by a Hindu finance minister. This seems to have had an almost unmatched success in that it actually led to increases in production, which raised the standard of living in Hindustan. Among other reforms, which were notable in intention if not in effect, was the discouragement of

suttee

.