The New Penguin History of the World (168 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The Russian state was destroyed by the war. This was the beginning of the revolutionary transformation of central and eastern Europe, too. The makers of what was called a ‘revolution’ in Russia in February 1917 were the German armies, who had in the end broken the hearts of even the long-enduring Russian soldiers, who had behind them cities starving because of the breakdown of the transport system and a government of incompetent and corrupt men who feared constitutionalism and liberalism as much as defeat. At the beginning of 1917 the security forces themselves could no longer be depended upon. Food riots were followed by mutiny and the autocracy was suddenly seen to be powerless. A provisional government of liberals and socialists was formed and the Tsar abdicated. The new government itself then failed, in the main because it attempted the impossible, the continuation of the war; the Russians wanted peace and bread, as Lenin, the leader of the Bolsheviks, saw. His determination to take power from the moderate provisional government was the second reason for their failure. Presiding over a disintegrating country, administration and army, still facing the unsolved problems of privation in the cities, the provisional government was itself swept away in a second change, the coup called the October Revolution which, together with the American

entry into the war, marks 1917 as a break between two eras of European history. Previously, Europe had settled its own affairs; now the United States would be bound to have a large say in its future. And there had come into being a state which was committed by the beliefs of its founders to the destruction of the whole pre-war European order, a truly and consciously revolutionary centre for world politics.

The immediate and obvious consequence of the establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), as Russia was now called, after the workers’ and soldiers’ councils which were its basic political institution after the revolution, was a new strategic situation. The Bolsheviks consolidated their

coup d’état

by dissolving (since they did not control it) the only freely elected representative body based on universal suffrage Russia ever had and by trying to secure the peasants’ loyalties by promises of land and peace. This was essential if they were to survive; the backbone of the party which now strove to assert its authority over Russia was the very small industrial working class of a few cities. Only peace could provide a safer and broader foundation. At first the terms demanded by the Germans were thought so objectionable that the Russians stopped negotiation; they then had to accept a much more punitive outcome, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, in March 1918. It imposed severe losses of territory, but gave the new order the peace and time it desperately needed to tackle its internal troubles.

The Allies were furious. They saw the Bolsheviks’ action as a treacherous defection. Nor was their attitude towards the new regime softened by the intransigent revolutionary propaganda it directed against their citizens. The Russian leaders expected a revolution of the working class in all the advanced capitalist countries. This gave an extra dimension to a series of military interventions in the affairs of Russia by the Allies. Their original purpose was strategic, in that they hoped to stop the Germans exploiting the advantage of being able to close down their eastern front, but they were quickly interpreted by many people in the capitalist countries and by all Bolsheviks as anti-communist crusades. Worse still, they became entangled in a civil war which seemed likely to destroy the new regime. Even without the doctrinal filter of Marxist theory through which Lenin and his colleagues saw the world, these episodes would have been likely to have soured relations between Russia and the capitalist countries for a long time; once translated into Marxist terms they seemed a confirmation of an essential and ineradicable hostility. Memories of this influenced Russian leaders for the next fifty years. They also helped to justify the Russian revolution’s turn downwards into authoritarian government. Fear of the invader as a restorer of the old order and patron of landlords combined

with Russian traditions of autocracy and police terrorism to stifle any liberalization of the regime.

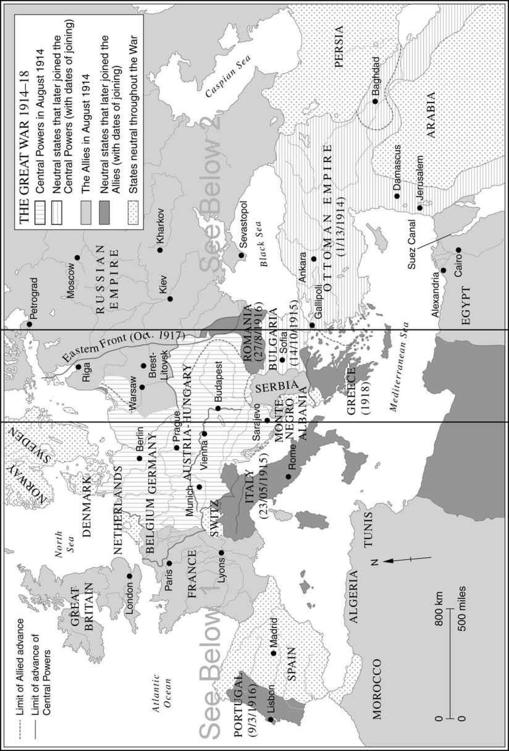

The Russian communists’ conviction that revolution was about to occur in central and western Europe was in one sense correct, yet crucially wrong. In its last year, the war’s revolutionary potential indeed became plain, but in national, not class, forms. The Allies were provoked (in part by the Bolsheviks) to a revolution strategy of their own. The military situation looked bleak for them at the end of 1917. It was obvious that they would face a German attack in France in the spring without the advantage of a Russian army to draw off their enemies, and that it would be a long time before American troops arrived in large numbers to help them in France. But they could adopt a revolutionary weapon. They could appeal to the nationalities of the Austro-Hungarian empire and no longer had to stand by their treaty of agreement with tsarist Russia. This had the additional advantage of emphasizing in American eyes the ideological purity of the Allied cause now that it was no longer tied to tsardom. Accordingly, in 1918, subversive propaganda was directed at the Austro-Hungarian armies and encouragement was given to Czechs and South Slavs in exile. Before Germany gave in, the Dual Monarchy was already dissolving under the combined effects of reawakened national sentiment and a Balkan campaign which at last began to provide victories. This was the second great blow to old Europe. The political structure of the whole area bounded by the Urals, the Baltic and the Danube valley was now in question as it had not been for centuries. There was even a Polish army again in existence. It was patronized by the Germans as a weapon against Russia, while the American president announced that an independent Poland was an essential of Allied peacemaking. All the certainties of the past century seemed to be in the melting-pot.

The crucial battles were fought against this increasingly revolutionary background. By the summer, the Allies had managed to halt the last great German offensive. It had made huge gains, but not enough. When the Allied armies began to move forward victoriously in their turn, the German leaders sought an end: they, too, thought they saw signs of revolutionary collapse at home. When the Kaiser abdicated, the third of the dynastic empires had fallen; the Habsburgs had already gone, so that the Hohenzollerns just outlasted their old rivals. A new German government requested an armistice and the fighting came to an end.

The cost of this huge conflict has never been adequately computed. One figure which is approximate indicates its scale: about ten million men had died as a result of direct military action. Yet typhus probably killed another million in the Balkans alone. Nor do even these horrible figures indicate

the physical cost in maiming, blinding, or the loss to families of fathers and husbands, the spiritual havoc in the destruction of ideals, confidence and goodwill. Europeans looked at their huge cemeteries and were appalled at what they had done. The economic damage was immense, too. Over much of Europe people starved. A year after the war manufacturing output was still nearly a quarter below that of 1914; Russia’s was only 20 per cent of what it had then been. Transport was in some countries almost impossible to procure. Moreover, all the complicated, fragile machinery of international exchange was smashed and some of it could never be replaced. At the centre of this chaos lay, exhausted, a Germany which had been the economic dynamo of central Europe. ‘We are at the dead season of our fortunes,’ wrote J. M. Keynes, a young British economist at the peace conference. ‘Our power of feeling or caring beyond the immediate questions of our own material well-being is temporarily eclipsed… We have been moved beyond endurance, and need rest. Never in the lifetime of men now living has the universal element in the soul of man burnt so dimly.’

Delegates to a peace conference began to assemble at the end of 1918. It was once the fashion to emphasize their failures, but perspective and the recognition of the magnitude of their tasks impose a certain respect for what they did. It was the greatest settlement since 1815 and its authors had to reconcile great expectations with stubborn facts. The power to make the crucial decisions was remarkably concentrated: the British and French prime ministers and the American president, Woodrow Wilson, dominated the negotiations. These took place between the victors; the defeated Germans were subsequently presented with their terms. In the diverging interests of France, aware above all of the appalling danger of any third repetition of German aggression, and of the Anglo-Saxon nations, conscious of standing in no such peril, lay the central problem of European security, but many others surrounded and obscured it. The peace settlement had to be a world settlement. It not only dealt with territories outside Europe – as earlier great settlements had done – but many non-European voices were heard in its making. Of twenty-seven states whose representatives signed the main treaty, a majority, seventeen, lay in other continents. The United States was the greatest of these; with Japan, Great Britain, France and Italy she formed the group described as the ‘principal’ victorious powers. For a world settlement, nevertheless, it was ominous that no representative attended from Russia, the only great power with both European and Asian frontiers.

Technically, the peace settlement consisted of a group of distinct treaties made not only with Germany, but with Bulgaria, Turkey and the ‘succession states’ which claimed the divided Dual Monarchy. Of these a resurrected Poland, an enlarged Serbia called the ‘kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes’ (and, later, ‘Yugoslavia’) and an entirely new Czechoslovakia were present at the conference as allies, while a much reduced Hungary and the Germanic heart of old Austria were treated as defeated enemies with whom peace had to be made. All of this posed difficult problems. But the main concern of the Peace Conference was the settlement with Germany embodied in the Treaty of Versailles signed in June 1919.

This was a punitive settlement and explicitly stated that the Germans were responsible for the outbreak of war. But most of the harshest terms arose not from this moral guilt but from the French wish, if possible, so to tie Germany down that any third German war was inconceivable. This was the purpose of economic reparations, which were the most unsatisfactory part of the settlement. They angered Germans and made acceptance of defeat even harder. Moreover they were economic nonsense. Nor was the penalizing of Germany supported by arrangements to ensure that Germany might not one day try to reverse the decision by force of arms, and this angered the French. Germany’s territorial losses, it went without saying, included Alsace and Lorraine, but were otherwise greatest in the east, to Poland. In the west the French did not get much more reassurance than an undertaking that the German bank of the Rhine should be ‘demilitarized’.

The second leading characteristic of the peace was its attempt where possible to follow the principles of self-determination and nationality. In many places this merely meant recognizing existing facts; Poland and Czechoslovakia were already in existence as states before the peace conference met, and Yugoslavia was built around the core of the former Serbia. By the end of 1918, therefore, these principles had already triumphed over much of the area occupied by the old Dual Monarchy (and were soon to do so also in the former Baltic provinces of Russia). After outlasting even the Holy Roman Empire, the Habsburgs were gone at last and in their place appeared states which, though not uninterruptedly, were to survive most of the rest of the century. The principle of self-determination was also followed in providing that certain frontier zones should have their destiny settled by plebiscite.