The New Penguin History of the World (114 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

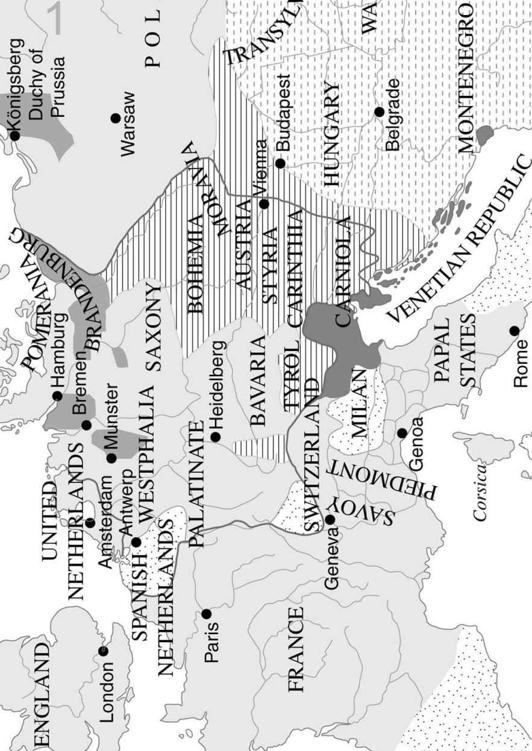

The Peace of Westphalia which ended the Thirty Years’ War in 1648

was in several ways a registration of change. Yet it showed traces still of the fading past. This makes it a good vantage-point. It was the end of the era of religious wars in Europe; for the last time European statesmen had as one of their main concerns in a general settlement the religious future of their peoples. It also marked the end of Spanish military supremacy and of the dream of reconstituting the empire of Charles V. It closed, too, an era of Habsburg history. In Germany a new force had appeared in the Electorate of Brandenburg, with which later Habsburgs would contend, but the frustration of Habsburg aims in Germany had been the work of outsiders, Sweden and France. Here was the real sign of the future: a period of French ascendancy was beginning in Europe west of the Elbe. In a still longer perspective it opened a period during which the underlying issues of European diplomacy were to be the balance of power in Europe, both east and west, the fate of the Ottoman empire, and the distribution of global power.

A century and a half after Columbus, though, when Spain, Portugal, England, France and Holland all already had important overseas empires, these were apparently of no interest to the authors of the peace of 1648. England was not even represented at either of the centres of negotiation; she had hardly been concerned in events once the first phase of the war was over. Preoccupied by internal quarrels and troubled by her Scottish neighbours, her foreign policy was directed towards ends more extra-European than European – though it was these ends which soon led her to fight the Dutch (1652–4). Although Cromwell quickly restored peace, telling the Dutch there was room in the world for both of them to trade, English and Dutch diplomacy was already showing more clearly than that of other nations the influence of commercial and colonial interest.

French ascendancy on the continent was founded on solid natural advantages. France was the most populous state of western Europe and on this simple fact rested French military power until the nineteenth century; it would always require the assembling of great international forces to contain it. France, however miserably poor its inhabitants may seem to modern eyes, had great economic resources, and was able to sustain a huge efflorescence of power and prestige under Louis XIV. His reign began formally in 1643, but actually in 1661 when, at the age of twenty-two, he announced his intention of managing his own affairs. This assumption of supreme power was a great fact in international as well as French history; Louis was the most consummate exponent of the trade of kingship who has ever lived. Only for convenience may his foreign policy be distinguished from other aspects of his reign. The building of Versailles, for example, was not only the gratification of a personal taste, but an exercise in building a

prestige essential to his diplomacy. Similarly, though they may be separated, his foreign and domestic policy were closely entwined with one another and with ideology. Louis wanted to improve the strategical shape of France’s north-western frontier, but also (though he might buy millions of tulip bulbs a year from them for Versailles) he despised the Dutch as merchants, disapproved of them as republicans, and detested them as Protestants. In him lived the spirit of the militant Counter-Reformation. Nor was that all. Louis was a legalistic man – kings had to be – and he felt easier when there existed legal claims good enough to give respectability to what he was doing. This was the complicated background to a foreign policy of expansion. Though in the end it cost his country dearly, it carried France to a pre-eminence from which she was to freewheel through half the eighteenth century, and created a legend to which Frenchmen still look back with nostalgia.

Louis’s wish for an improved frontier meant conflict with Spain, still in possession of the Spanish Netherlands and the Franche-Comté. The defeat of Spain opened the way to war with the Dutch. The Dutch held their own, but the war ended in 1678 with a peace usually reckoned the peak of Louis’s achievement in foreign affairs. He now turned to Germany. Besides territorial conquest, he sought the imperial crown and to obtain it was willing to ally with the Turk. A turning-point came in 1688, when William of Orange, the Stadtholder of Holland, took his wife Mary Stuart to England to replace her father on the English throne. From this time Louis had a new and persistent enemy across the Channel, instead of the complaisant Stuart kings. Dutch William could deploy the resources of the leading Protestant country and, for the first time since the days of Cromwell, England fielded an army on the continent in support of a league of European states (even the pope joined it secretly) against Louis. King William’s War (also called the War of the League of Augsburg) brought together Spain and Austria, as well as the Protestant states of Europe, to contain the overweening ambition of the French king. The peace which ended it was the first in which he had to make concessions.

In 1700 Charles II of Spain died childless. It was an event Europe had long awaited, for he had been a sickly, feeble-minded fellow. Enormous diplomatic preparations had been made for his demise because of the great danger and opportunity which it must present. A huge dynastic inheritance was at stake. A tangle of claims arising from marriage alliances in the past meant that the Habsburg emperor and Louis XIV (who had passed his rights in the matter on to his grandson) would have to dispute the matter. But everyone was interested. The English wanted to know what would happen to the trade of Spanish America, the Dutch the fate of the Spanish

Netherlands. The prospect of an undivided inheritance going either to Bourbon or Habsburg alarmed everybody. The ghost of Charles V’s empire walked again. Partition treaties had therefore been made. But Charles II’s will left the whole Spanish inheritance to Louis’s grandson. Louis accepted it, setting aside the agreements into which he had entered. He also offended the English by recognizing the exiled Stuart Pretender as James III of England. A Grand Alliance of Emperor, United Provinces and England was soon formed, and there began the War of the Spanish Succession, twelve years’ fighting which eventually drove Louis to terms. By treaties signed in 1713 and 1714 (the Peace of Utrecht), the crowns of Spain and France were declared forever incapable of being united. The first Bourbon king of Spain took his place on the Spanish throne, though, taking with Spain the Indies but not the Netherlands, which went to the emperor as compensation and to provide a tripwire defence for the Dutch against further French aggression. Austria also profited in Italy. France made concessions overseas to Great Britain (as it was after the union of England with Scotland in 1707). The Stuart Pretender was expelled from France and Louis recognized the Protestant succession in England.

These important facts assured the virtual stabilization of western continental Europe until the French Revolution seventy-five years later. Not everyone liked it (the emperor refused to admit the end of his claim to the throne of Spain) but to a remarkable degree the major definitions of western Europe north of the Alps have remained what they were in 1714. Belgium, of course, did not exist, but the Austrian Netherlands occupied much of what is now that country, and the United Provinces corresponds to the modern Netherlands. France would keep Franche-Comté and, except between 1871 and 1918, the Alsace and Lorraine which Louis XIV had won for her. Spain and Portugal would after 1714 remain separate within their present boundaries; they still had large colonial empires but were never again to be able to deploy their potential strength so as to rise out of the second rank of powers. Great Britain was the new great power in the west; since 1707, England no longer had to bother about the old Scottish threat, although once more attached by a personal connection to the continent because after 1714 her rulers were also Electors of Hanover. South of the Alps, the dust took longer to settle. A still disunited Italy underwent another thirty-odd years of uncertainty, minor representatives of European royal houses shuffling around it from one state to another in attempts to tie up the loose ends and seize the left-overs of the age of dynastic rivalry. After 1748 there was only one important native dynasty left in the peninsula, that of Savoy, which ruled Piedmont on the south side of the Alps and the island of Sardinia. The papal states, it is true, could since the fifteenth century be regarded as an Italian monarchy, though only occasionally a dynastic one, and the decaying republics of Venice, Genoa and Lucca also upheld the tattered standard of Italian independence. Foreign rulers were installed in the other states.

Western political geography was thus set for a long time. Immediately, this owed much to the need felt by all statesmen to avoid for as long as possible another conflict such as that which had just closed. For the first time a treaty of 1713 declared the aim of the signatories to be the security of peace through a balance of power. So practical an aim was an important innovation in political thinking. There were good grounds for such realism; wars were more expensive than ever and even Great Britain and France, the only countries in the eighteenth century capable of sustaining war against other great powers without foreign subsidy, had been strained. But the end of the War of the Spanish Succession also brought effective settlements of real problems. A new age was opening. Outside Italy, much of the political map of the twentieth century was already visible in western Europe. Dynasticism was beginning to be relegated to the second rank as a principle of foreign policy. The age of national politics had begun, at least for some princes who felt they could no longer separate the interests of their house from those of their nation.

East of the Rhine (and still more east of the Elbe) none of this was true. Great changes had already occurred there and many more were to come before 1800. But their origins have to be traced back a long way, as far as the beginning of the sixteenth century. At that time Europe’s eastern frontiers were guarded by Habsburg Austria and a vast Polish-Lithuanian kingdom ruled by the Jagiellons, which had been formed by marriage in the fourteenth century. They shared with the maritime empire of Venice the burden of resistance to Ottoman power, the supreme fact of east European politics at that moment.

The phrase ‘Eastern Question’ had not then been invented; if it had been, it would have meant then the problem of defending Europe against Islam. The Turks went on winning victories and making conquests as late as the eighteenth century, though by then their last great effort was spent. For more than two centuries after the capture of Constantinople, nevertheless, they had set the terms of eastern European diplomacy and strategy. That capture was followed by more than a century of naval warfare and Turkish expansion, from which the main sufferer was Venice. While it long remained rich by comparison with other Italian states, Venice suffered a relative decline, first in military and then in commercial power. The first, which led to the second, was the result of a long losing battle against the Turks, who in 1479 took the Ionian islands and imposed an annual charge

for trade in the Black Sea. Though Venice acquired Cyprus two years later, and turned it into a major base, it was in its turn lost in 1571. By 1600, though still (thanks to her manufacturers) a rich state, Venice was no longer a mercantile power at the level of the United Provinces or even England. First Antwerp and then Amsterdam had eclipsed her. Turkish success was interrupted in the early seventeenth century but then resumed; in 1669 the Venetians had to recognize that they had lost Crete. Meanwhile, Hungary became in 1664 the last Turkish conquest of a European kingdom, though the Ukrainians soon acknowledged Turkish suzerainty and the Poles had to give up Podolia. In 1683 the Turks opened their second siege of Vienna (the first had been a century and a half before) and Europe seemed in its greatest danger for over two centuries. In fact it was not. This was to be the last time Vienna was besieged, for the great days of Ottoman power were over.