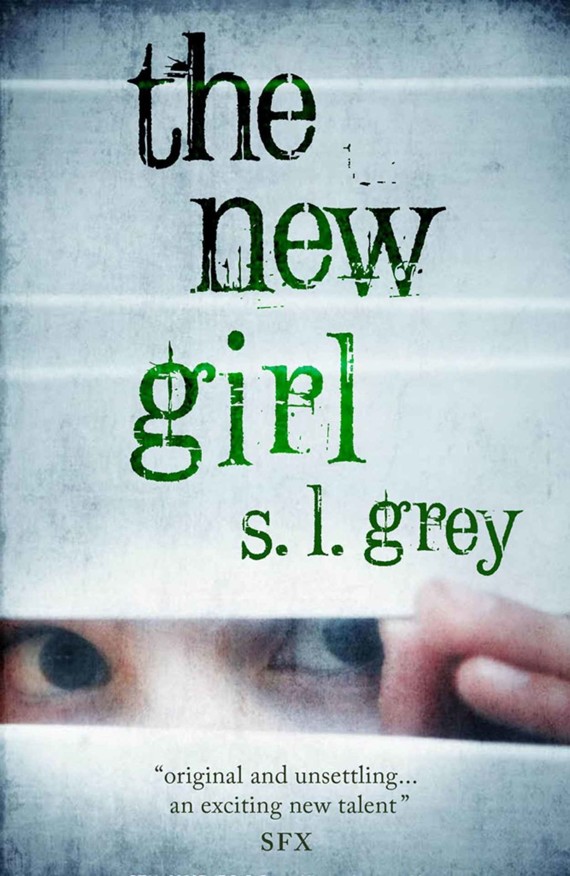

The New Girl (Downside)

Read The New Girl (Downside) Online

Authors: S.L. Grey

S.L. Grey is a collaboration between Sarah Lotz and Louis Greenberg. Based in Cape Town, Sarah writes crime novels and thrillers under her own name, and as Lily Herne she and

her daughter Savannah Lotz write the

Deadlands

series of zombie novels for young adults. Louis is a Johannesburg-based fiction writer and editor who worked in the book trade for many

years. He has a Master’s degree in vampire fiction and a doctorate in post-religious apocalyptic fiction.

Also by S.L. Grey

The Mall

The Ward

Published in paperback in Great

Britain in 2013 by Corvus, an imprint

of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © S.L. Grey, 2013

The moral right of S.L. Grey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual

persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 0 85789 592 9

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 591 2

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S.L. Grey thanks: Lauren Beukes, Adam Greenberg, Sam Greenberg, Bronwyn Harris, Sarah Holtshausen, Alan Kelly, Savannah Lotz, Charlie Martins, Helen Moffett, Oli Munson, Sara

O’Keeffe, Laura Palmer, Lucy Ridout, Alan and Carol Walters, Maddie West, Naomi Wicks and Corinna Zifko.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Ryan slices his hand on a loose snarl of guttering. He jerks his arm away and the light bulb slips out of his hand.

‘Look out!’

The ladder judders and he braces himself against the aluminium rungs, watching the kids below him scattering backwards, tripping over their feet, bumping into each other in their urgency to

move. All but one. A new girl he’s never seen before drifts there, under the ladder, as if she hasn’t heard him shout, as if she doesn’t see the other children scurrying. The

girl’s hair is pale – a strawy yellow that looks artificial. The space around her is a void. The other kids don’t look at her. The light bulb whistles an inch from her face and

smashes at her feet with a hollow plock. She stops moving, but doesn’t even look up.

The flexible frame of the ladder still bucks, and Ryan grips on tighter. Even though he’s only two nouveau-kitsch, architect-designed, concrete-and-veneer high-school storeys above the

ground, he imagines himself shattering on the walkway like that fragile glass orb.

‘Mr Devlin,’ calls out a voice from below. ‘Mr Devlin!’

It’s the headmaster, totally overdressed in a dark suit. ‘Yes, Mr Duvenhage.’

‘Are you all right up there?’

‘Yes, sir.’ There was a time when Ryan would never have said ‘sir’ to a man like this, but now he knows what greases the wheels, what makes life easier.

‘Do try to be careful, would you?’

‘Yes, sir,’ Ryan says cheerfully. One good thing about becoming a blue-collar worker at the age of thirty-eight is that he feels a righteous resentment towards the managing classes.

Solidarity with the workers. He now understands what lies behind those blank, passive-aggressive looks he got from labourers on the side of the road, or in the backs of trucks he used to trail in

his car. It’s hatred; a blanket, undifferentiated loathing. The same way he feels towards this little jerk barking orders below him. Their mistake, the reason they’re still at the side

of the road, on the back of that truck, is that they show it.

‘And Mr Devlin...’

‘Yes, sir?’

‘You’re dripping.’ The man grimaces and steps backwards daintily before turning around and scuttling off.

Ryan looks at his slashed palm, clasps his hands together in an effort to staunch the flow, but watches with perverse fascination as the blood oozes its way between his palms and snakes down his

forearm. Blood always finds a way out.

The flow gathers at his elbow, clotting with the late-summer sweat on his skin, collecting into a syrupy gout before reluctantly letting go and falling slickly. The kids have moved off along

their lines like bees in an intricate dance. Except, right below him – he almost didn’t notice; she is half obscured by his body – the new girl. She’s like nobody he’s

ever seen before. She looks so thoroughly disconnected from the school kids around her. She doesn’t move like other people. Most move along their predestined tracks just as they should, react

to stimuli and repulsion just like idealised bodies in a science experiment. Occasionally they shunt off their path just a little – you can notice it in their lost expressions – but

then they always correct their own course. Ryan sizes people up quickly, he knows where they fit. But this girl... she magnetises him like no other girl has before.

As he watches her, his hands clasped, noticing how she exerts no gravitational pull or push on the other kids passing by, a clotty drop of his blood hits her on the head, staining the long,

straight, yellow hair like a stabbed duckling. Anyone else would look up, but she doesn’t. She looks at her reflection in the ground-floor window. She calmly slides a middle finger over the

blood on her head, then brings her hand down to look at it. She smears her thumb over the blood on the tip of her middle finger intently. Curiously.

Then, way after she should have, she tilts her head backwards and looks up at Ryan, clamped against the ladder’s stilled struts. She stares at him, expressionless, causing Ryan to feel

something very wrong. Then she lowers her head mechanically and continues to drift her void through the web of relationships in the yard below.

Ryan washes and disinfects his hand in the sink in the maintenance quarters, takes a pull of Three Ships from the bottle in his locker and breathes the fumes out tremulously,

bracing himself against the clammy metal of the lockers.

‘Eita, Ryan.’ Thulani Duma, the school’s chief groundsman, essentially Ryan’s direct superior, comes in, the blue hibiscus of his Hawaiian shirt showing through his

buttoned-down overalls. He taps his watch and shakes his head microscopically. ‘Mr Duvenhage wants to see you.’

‘Hmm, what now?’

Thulani shrugs.

Ryan rinses with the Listerine in his locker, knowing as he does it that the reek of mouthwash is more damning than any waft of whisky. He wonders why it matters. When he was a scholar at his

dark, faux-Gothic government-funded boys’ school, all the senior teachers were drunk half the time. It’s the same at Alice’s expensive Catholic private school... It’s all

about the show, of course. They can behave how they want as long as they look right doing it. Ryan can picture men like Duvenhage going home and beating his wife and kid – something Ryan

never did, even in the worst of it – then cruising the streets in his tame sedan and raping some street child. He beams that sort of malice from those tiny eyes of his, tucked away behind

that unctuous rubber smile and that fussy haircut.

Ryan’s aware, as he announces himself to the school’s ‘executive secretary’, that the ‘Crossley College’ stitched across the back of his blue overalls brands

him. Property of the school. And since when did schools start needing ‘executive secretaries’ in the first place? This is apparently one of the innovations Duvenhage brought in when he

joined the school at the beginning of the year, one of the wave of school administrators who take more pride in their MBAs than their teaching diplomas. Sybil Fontein is a fifty-something,

thin-lipped, uptight bitch who reeks of her failure to land a job as a corporate PA. She treats her position as a portal to Duvenhage’s petty majesty like some sort of holy penance. One day,

having cleansed herself sufficiently, she might climb a rung and become – what? – a vestal sacrifice at the monthly meeting of the school governing body?

Ryan shakes off the image before it becomes too deeply lodged in his mind. Graphic images are at the root of his problems, this urge to actuate what he sees in his mind. He’s never quite

been able to separate the real world from the pictures in his mind.

He sits nonchalantly on the hard wooden bench outside the principal’s office while, in the alcove opposite, Sybil Fontein makes a huffy show of filing papers and clattering on her

keyboard. She looks up at him with distaste – the grubby help occupying her space – but then he smiles and she blushes and quickly looks down again. He knows she’ll look at him

again. Three, two, one – there we go – and this time the look on her face is more inviting. Ryan knows what works.

At length Duvenhage pokes his head around his door. ‘Mr Devlin. Come inside, please.’

Like the rest of the school, the office is decorated in pale earth tones, with broad plate-glass windows, stone tiles and blond-wood furnishings. It’s expensive and new – just eight

years old, as its shammy coat of arms with the ‘Est.’ date below it proclaims – and not what Ryan imagines when he thinks of school. It’s more like one of those corporate

office parks. But as much as the rich parents are prepared to pay to keep their children out of the overcrowded, underfunded, directionless mess of South African state education, it’s still

fraying at the edges, and that, Ryan supposes, is why he has a job. The ceiling boards in this office are sagging and there’s an invasion of rising damp and mildew eating through the wall

where it abuts the picture window. Hurried architecture and shoddy work. Ryan goes to the corner to inspect the damp more closely.

But Duvenhage indicates a chair at his desk. ‘Sit, please, Mr Devlin.’