The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble (29 page)

Read The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble Online

Authors: Addison Wiggin,William Bonner,Agora

Tags: #Business & Money, #Economics, #Economic Conditions, #Finance, #Investing, #Professional & Technical, #Accounting & Finance

Not since the reign of Diocletian had such a powerful empire attempted such an idiotic thing. As part of the big changes in 1971, Nixon created the Cost of Living Council, organized specifically to administer a 90-day freeze on wage and price hikes. Although this temporary measure was removed, inflation returned. In June 1973, controls were reimposed, shortly before Nixon’s resignation. Finally, admitting that these policies did not work as hoped, the wage and price control plan was given up in April 1974 during the Ford administration.

Financially, the Vietnam War was a mess. The decision makers had no idea how much the war would cost, or how the bills would be paid. As early as 1965, the MacNamara team had an estimate from Army Chief of Staff General Harold K. Johnson that winning the war would require as many as 500,000 troops and five years of fighting. The policymakers were aghast. They were not prepared to commit to anything like that level of involvement—in terms of the numbers of men as well as the costs involved. The chairman of President Johnson’s Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) told the president in 1965,“The current thinking in DOD [Department of Defense], as relayed to me by Bob MacNamara on a super-confidential basis, points to a gradual and moderate build-up of expenditures and manpower.”

2

The debate over the real costs of the war continued throughout the entire period from 1964 through 1968. It wasn’t until late 1967, however, that LBJ asked Congress for a 10 percent tax surcharge. That surcharge was approved by mid-1968, but only on condition that Johnson also cut $6 billion from domestic programs—a requirement that hurt him dearly. His beloved Great Society programs, half of the “guns-and-butter” policy defining his presidency, ultimately were curtailed by the escalating costs of the war in Vietnam. But neither the costs of the war nor those of the Great Society were cut enough.

The total spent by the United States on the Vietnam War amounted to more than $500 billion in today’s money.That is a lot of money at any time. At first, Johnson assured the nation that the war would not jeopardize his other promises. He had pledged to give away billions of other people’s money; the offer was still good, he said. He told Congress in 1966, “I believe that we can continue the Great Society while we fight in Vietnam.”

3

As the costs mounted up, government budget officials and his own economic advisors began to worry. The math wasn’t working. The president’s guns-and-butter policy, a 1960s’ version of the Romans’ bread and circuses was too expensive. They realized they needed more revenue. Rising deficits and rising inflation levels in the United States worried foreign dollar holders, who began calling away America’s gold. Only higher tax revenues could cure the problem (see

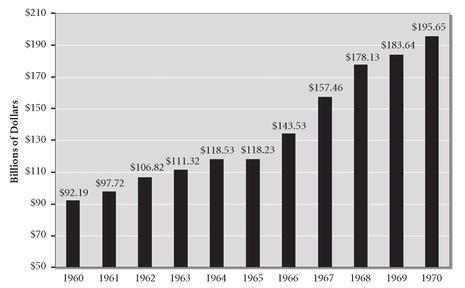

Figure 8.2

).

President Johnson stood his ground. He feared that “all hell will break loose,” if he were to request a tax increase. Congress would rather cut the butter than raise taxes or give up the guns. The result would be the end of the Great Society.

Lyndon Johnson had no money of his own to fund the Great Society programs he set in place. He could only give money to one voter by taking it away from another one. Peter had to be robbed if Paul was to be paid.

But theft is not murder, and not only will the majority of citizens in a democracy put up with a little thievery, they will welcome it—especially if it is done on their behalf. The most popular American presidents were those who stole most bountifully. The logic of democratic larceny is that there are always more voters receiving tax money than getting it taken from them. That is the real reason Democrats favor doing something “to help the poor”—there are more of them; you can buy their votes cheaply. Wave a $10 bill in front of a rich man and you will get little attention—in a trailer park, you will draw a crowd. Still, in a fluid society like the United States, there are also a lot of people who hope to get rich some day and want to look forward to holding onto their money if it ever comes their way. So, there is always a certain resistance to higher taxes, and in 1966 and 1967, Lyndon Johnson was loath to run into it.

Figure 8.2

Federal Outlays, 1960-1970

The total amount spent by the United States on the Vietnam War exceeded $500 billion in today’s money. Lyndon Johnson’s guns-and-butter policy, a 1960s’ version of the Romans’ bread and circuses, was too expensive. Rising deficits and inflation in the United States worried foreign dollar holders, who began calling away America’s gold.

Source

: “Historical Tables” Budget of the U.S. Government.

But there was resistance to bankrupting the country, too. There were still a few geezers in Congress who believed in balanced budgets. So, after the 1966 elections, Johnson’s 10 percent tax surcharge was presented.This, he said, would give the United States “staying power,” in its fight with communism. Robert MacNamara now claims that he knew the war was hopeless as early as 1964, so staying power was exactly what the United States didn’t need. What it needed was the courage to quit. But it is this courage that is most lacking in times of war. Men would rather die than admit that they are doing an asinine and pointless thing.

Johnson’s tax hike was opposed in the House by Minority Leader Gerald Ford and Ways and Means Committee Chairman Wilbur Mills.The southern Democrats and northern Republicans wanted spending cuts, not tax hikes. Johnson said:

They will live to rue the day when they made that decision, because it is a dangerous decision . . . an unwise decision . . . . I know it doesn’t add to your polls and your popularity to say we have to have additional taxes to fight this war abroad and fight the problems in our cities at home. But we can do it with the gross national product we have.We should do it. And I think when the American people and the Congress get the full story they will do it.

4

By 1968, the empire was going broke. Gold reserves were being depleted. Congress had to act, passing the 10 percent tax surcharge along with a budget cut of $18 billion (about a 10 percent cut in appropriations). Johnson had to melt some butter to get more guns.

At the time, Washington still operated on old-fashioned Keynesian economics and a gold standard. Economists believed government could spend more heavily in times of war or times of economic hardship (to “prime the pump”), but it was still widely agreed that what was borrowed must be paid back. Deficits still mattered, partly because they threatened the nation’s currency (and its gold backing), and partly because policymakers still thought they would have to make up overspending now by underspending in the future.

Then, as now, taxpayers could be squeezed, but only so hard and only if politically realistic. Otherwise, they would soon start to howl. Redistribution of wealth only works, politically, if someone else’s money is being passed around. Taxpayers don’t see any advantage in giving up their own money.

Liberal politicians in the 1960s advertised themselves much as George W. Bush does today.They said they were extending freedom at home as well as abroad.“How can anyone say that a nation with an income of more than $800 billion can’t afford a $30 billion war?” said Paul Douglas of Illinois.

5

“Military forces able to defend the cause of freedom in Vietnam and to counter other threats to national security require substantial resources.Yet we cannot permit the defense of freedom abroad to sidetrack the struggle for individual growth and dignity at home,” added Johnson.

Vice President Hubert Humphrey joined in, saying that America “can afford to extend freedom at home at the same time that it defends it abroad.”

6

“The United States is not faced—nor could it be faced—with a guns and butter choice . . . . This country has ample resources to prosecute the shooting war and still combat the shortcomings of our own society,” continued AFL-CIO president George Meany.

7

Nor did the people disagree. Americans favored more guns and more butter, over a reduction in spending on either front, by a margin of 48 percent to 39 percent, according to a Harris poll.

Until the Vietnam era, after every previous war was over, federal spending dropped. When the Vietnam War ended, however, federal spending continued to go up. The federal budget had been $184 billion in 1969 at the height of the military spending. In 1972, it rose to $231 billion. In 1969, the federal government actually ran a surplus of $3 billion. By 1972, with the war winding down, we expected to see the surpluses continue; but instead the surplus turned into a deficit of $23 billion.

The empire grew, and kept growing. Before launching the attack on the USSR, June 22, 1941, Hitler remarked that the Soviet Union was like a rickety old house. All we have to do, he said, was “kick in the door and the whole thing will fall down.” He was 48 years premature. The Soviet Union fell apart in 1989 by itself; America didn’t even have to kick in the door. But even after the Cold War was over, the federal budget continued to rise, from $1.14 trillion in 1989 to $1.38 trillion in 1992.

The Great Society

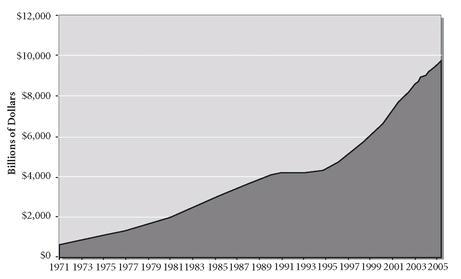

was merely the domestic wing of America’s new system of imperial finance. Johnson offered more bread and more circuses than any president before him. The five-year cost of administering the Great Society programs was estimated at $305.7 billion (in 2005 inflation-adjusted dollars).This does not include the $250 billion in college loans and grants to 29 million students since 1965 (see

Figure 8.3

).

The scope of the Great Society was massive, comparable to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs but on a more expensive scale. Even counting only Medicaid and Medicare, the LBJ idea has added trillions to U.S. future obligations:

During [the Johnson] administration, Congress enacted two major civil-rights acts (1964 and 1965), the Economic Opportunity Act (1964), and two education acts (1965). In addition, legislation was passed that created the Job Corps, Operation Head Start, Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), Medicaid, and Medicare. Although the Great Society program made significant contributions to the protection of civil rights and the expansion of social programs, critics increasingly complained that the antipoverty programs were ineffective and wasteful.

8

Figure 8.3

M3 Money Stock

The great cost of administering the empire requires an ever-expanding supply of the imperial currency. Since U.S. currency has become untethered to gold, the quantity of paper dollars floating around the globe has ballooned significantly, rendering each dollar a little less valuable than the last.

Source:

Federal Reserve.

This expansion had the consequence of creating massive bureaucracies within the federal system. Considering the Medicaid and Medicare costs alone, we have seen exponential growth in current and future obligations, impractical cost-benefit outcomes, widespread waste, and fraud within the medical establishment. The programs were expanded partly to counter growing unrest at home. We should recall that by the end of Johnson’s presidency, the country was disturbed. Race riots in the inner cities, massive antiwar protests, and clashes between students and police were commonplace from 1965 onward, and continued into Nixon’s reign.

People wanted more bread and circuses. Personal consumption expenditures had expanded significantly since the end of World War II. By 1970, annual expenditures were 4.5 times higher than in 1946. After 1971, when the pax dollarum system began, expenditures grew exponentially. By the year 2000, annual levels were at $6.68

trillion

—46 times higher than at the end of the Second World War.

But what followed Nixon immediately was an era of financial turmoil that has rarely been equaled in modern history.The U.S. dollar plunged precipitously; U.S. unemployment exceeded 10 percent; oil prices skyrocketed to $39 a barrel; the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell to 570; gold reached $800 an ounce; and U.S. inflation and interest rates climbed to double-digit levels.