The Nazis Next Door (39 page)

Read The Nazis Next Door Online

Authors: Eric Lichtblau

During a break in the talks one morning, in the middle of a snowstorm, he arranged for a side trip

to a nearby prison. A guard walked him down a long, cold cellblock. They stopped at a green metal door with the number 17 written in white at the top. This was Fruma’s cell. The place had been modernized and now served as a maximum-security prison—not for Jews, but for convicted criminals. But the cell was still there, seventy years later. Rosenbaum asked to look inside. The guard opened the door to reveal another door lined with metal bars—and a young man standing inside. The prisoner seemed happy to have company. He smiled broadly and waved at the visitor in the trench coat.

The young man had no idea of the cell’s history, but Rosenbaum did. He knew that Fruma Kaplan and her mother, Gitta, had spent three long weeks there in cell 17 in December of 1941 at the Lukiski “hard labor” prison after they had been discovered in hiding. He knew that Aleksandras Lileikis, with a swipe of his pen, had put them there—and that his next swipe of the pen sent them to their deaths.

Rosenbaum stood at the cell door in silence for a few minutes. When he had brought the case against Lileikis eighteen years earlier, his own daughter was six years old. He wondered what those three weeks must have been like for Fruma, sleeping in that godforsaken cell while Lileikis was in his office signing her death warrant. It must have been cold and dark on the concrete floor. He wondered if she knew the fate that awaited her. Had she ever heard the foreboding song sung in the ghetto?

All roads lead to Ponary, but no roads lead back

. At least Fruma and Gitta were together. They had each other.

Rosenbaum had another stop to make. He wanted to follow Fruma’s path. He wanted to go to Ponary. An oversize black SUV from the American Embassy in Vilnius took him and three American colleagues on a snowpacked road, six miles outside the city. It was a comfortable drive; nothing like the hellish trek that Fruma and Gitta would have endured en route from the prison. The Nazis had probably marched them on foot through the snow, with dozens of others, in a grim processional that cold December day. Or maybe, if they were lucky, mother and daughter avoided the march and rode in a Nazi truck packed with other hungry, filthy prisoners. Either way, they would have ended up at the edge of that horrible pit—the same one that Rosenbaum was now tramping through the deep snow to reach.

No one else was there, and the place was eerily quiet.

The clearing was blanketed in a sea of white, with a row of tall, arching pine trees giving way to a gentle slope. It was bucolic. In another place, this might have been the perfect setting for a little girl to go sledding. But here, the slope led down to a cavernous ring about twenty-five yards wide. Before the war it had been a petroleum excavation site. The ditch itself was now filled with snow, but the outer rim was still visible to the eye: a marker of horror. A stone memorial with a Star of David and a menorah carved on it marked the site. It was the closest thing to a gravestone that Fruma would ever have. Rosenbaum could almost picture what it must have been like for her and the many thousands of victims brought here: stripped down, lined up, shot dead. He hoped the end was short for Fruma. Maybe she was still together with her mother, as they had been for those three weeks in cell 17.

Standing at the edge of the ditch, Rosenbaum thought of Aleksandras Lileikis’s smugness in 1983.

Show me something that I signed

. It had taken a long time, too long, but the Justice Department had finally shown him something. They finally got him. That held special importance to Rosenbaum. To outsiders who hadn’t seen the things he had seen, Lileikis might have seemed like just another Nazi who made it into America, but it was more than that for Rosenbaum. He had taken down Lileikis for Fruma’s memory. The bastard who signed her death warrant had died in disgrace, haunted by his past.

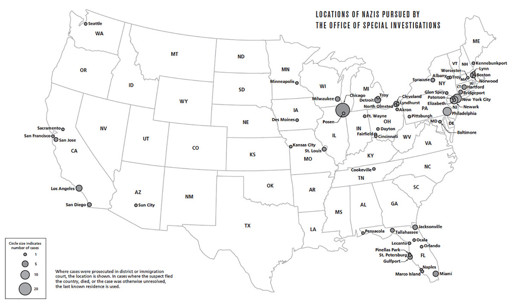

Rosenbaum had been at this for nearly thirty years. What started as a summer internship in an office that was supposed to be around for only a few years had instead turned into a career spent chasing Nazis. He knew what some people called him: a zealot, a man too emotional about his job to see things through the sober lens of law enforcement. He always winced at the word, but if being a zealot meant he was passionate about chasing Nazis, so be it. That much he would admit. In his time there, the Justice Department had brought more than one hundred successful denaturalization and deportation cases against Americans with Nazi ties. It was justice delayed, but it was something. How many others had gotten away? How many other Eichmann aides and SS officers and Sobibor guards and Nazi collaborators in America had lived out their lives undiscovered? Hundreds, certainly,

Rosenbaum knew. Thousands, probably. Perhaps even more than ten thousand,

as another Justice Department prosecutor had once estimated. The truth was that no one really knew, because the United States had made it so easy for them to fade seamlessly into the fabric of the country. America’s disinterest in Nazis after the war was so prolonged, its obsession with the Cold War so acute, its immigration policies so porous, that Hitler’s minions had little reason to fear they would be discovered. How many Nazis had lived and died quietly as free men in their adopted country, with their death notices silent about their horrific crimes? Too many, Rosenbaum knew. That was the only real answer. However many Nazis had called America their home after the war, it was too many.

Rosenbaum peered one last time at the snow-covered pit. It now looked so deceptively peaceful, nothing like the godforsaken place it must have been seven decades earlier. He trudged through the deep snow, making his way back down the hill, back down the road from Ponary that the Jews in the ghetto used to sing about as they awaited their certain deaths. They never had the chance to take the road back out of Ponary, but Rosenbaum did. He got back in the SUV. He still had a few more Nazis left to

chase.

Epilogue

In 2010, a secret internal history of the government’s decades-long hunt for war criminals concluded that the United States became a refuge for the Nazis after World War II. “America, which prided itself on being a safe haven for the persecuted, became—in some small measure—a safe haven for persecutors as well,” the Justice Department report acknowledged.

Sixty-five years after the war, it was the first time the U.S. government had made such a stark admission.

In 2011, a German court convicted John Demjanjuk, the onetime Ohio autoworker, of taking part in the murders of twenty-eight thousand prisoners as a guard at Sobibor. The ninety-one-year-old Demjanjuk lay motionless in a cot set up for him in the courtroom as the verdict was read. In a case that had proven such a black eye for the U.S. Justice Department for decades, prosecutors maintained that justice had finally been achieved.

Demjanjuk died the next year, claiming innocence until the end.

In 2012, with Tom Soobzokov’s murder still unsolved after more than a quarter century, his son pressed authorities to reopen the

investigation. Internal FBI documents showed that agents in the 1980s tracked several Jewish militants in the United States and Israel who were suspected in the bombing at Soobzokov’s New Jersey home and in three other pipe-bombings linked to it. Soobzokov’s son, Aslan, charged as part of a lawsuit that prosecutors failed to bring charges against anyone because of his father’s notoriety as a Nazi.

The lawsuit was ultimately tossed out, and the Supreme Court refused to hear the case. The bombings remain unsolved.

In 2013, pressure from its own scientists led the Space Medicine Association to stop giving out its annual Strughold Award, named for “the father of space medicine,” Dr. Hubertus Strughold, one of the first Nazi scientists brought to America in Project Paperclip. While Dr. Strughold’s name had been dropped years earlier from a number of other tributes, the space association had been the final holdout. It finally bowed to complaints from scientists who were uncomfortable with the idea of honoring a man implicated in gruesome Nazi medical experiments.

Prosecutors continued investigating some of the surviving Paperclip scientists into the twenty-first century. Among them was Wernher von Braun’s brother, Magnus, a rocket engineer in the V-2 slave-labor camp at Dora who also came to America under Paperclip. Prior to his death in Arizona in 2003, prosecutors were still scrutinizing Magnus von Braun’s wartime role with the Nazis. Only one Nazi scientist—von Braun’s deputy, Arthur Rudolph, the engineer forced out of the United States in 1984—was ever prosecuted in America for his work with the Nazis.

In 2014, authorities arrested one of America’s last surviving Nazis—eighty-nine-year-old Johann Breyer—at his red brick townhouse in Philadelphia. He was charged with taking part in the gassings of 216,000 Jews at Auschwitz as a Nazi “Death’s Head” guard at the concentration camp. Breyer, who volunteered for the SS at age seventeen in his native Czechoslovakia, admitted being a guard at Auschwitz, but insisted he had nothing to do with the notorious killing operations. Prosecutors did not believe him, and a judge in July ordered him sent back to Germany to face war crimes charges. Seven decades had not dulled his involvement in “Nazi atrocities against humanity,” the judge said.

“No statute of limitations offers a safe haven for murder,” he wrote.

But for the onetime Auschwitz guard and thousands of Nazis like him, America had proven to be exactly that: a safe haven for Hitler’s men, a place where unthinkable war crimes were easily concealed and quickly forgotten.

On the very day he was ordered back to Germany, Johann Breyer died in a Philadelphia hospital. The retired toolmaker had lived freely in his adopted country for sixty-two years.

“He’s been hiding in plain sight,” said the daughter of two Holocaust survivors in Philadelphia, “and, well, he got away with it. He lived a long life.”

Acknowledgments

This book could not have been written without guidance and input from dozens of people. While I have spent the past two and a half years following the Nazis’ trail into America, many of those on whom I relied have spent their entire careers immersed in understanding the Holocaust, a topic as important and unfathomable today as it was seven decades ago.

Among more than 150 Holocaust researchers, survivors, prosecutors, lawyers, and others I interviewed, a number deserve particular thanks. They include Peter Black, Ralph Blumenthal, Richard Breitman, Martin Dean, Judy Feigin, Jeff Mausner, Martin Mendelsohn, Michael Neufeld, Eli Rosenbaum, Allan Ryan, Rochelle Saidel, Paul Shapiro, Neal Sher, Art Sinai, Michael Sussmann, and Mark Talisman. I am also grateful to Gus von Bolschwing, Aslan Soobzokov, and Rad Artukovic for their cooperation.

I reviewed some forty-five hundred pages of archival documents, declassified intelligence reports, and government filings in my research, relying on a number of researchers. Bob Elston plowed the early ground and provided critical insight every step of the way. Jacob Brunell, Kitty Bennett, Vincent Slatt, and Cary Caldwell were of great help as well.

Two works were invaluable. An internal Justice Department report,

The Office of Special Investigations:

Striving for Accountability in the Aftermath of the Holocaust

, by Judy Feigin, which I first wrote about in the

New York Times

in 2010, provided the impetus for this book and proved an exhaustive resource.

U.S

.

Intelligence and the

Nazis

, by Richard Breitman, Norman J. W. Goda, Timothy Naftali, and Robert Wolfe, was indispensable as well.

I am also indebted to friends and colleagues who took the time to read rough drafts. Lenny Bernstein, Bob Elston, Kevin Johnson, Marc Lacey, and Scott Shane helped shape the manuscript from something barely readable to its current form. Martin Kanovsky and Ellen Teller, Anita Lichtblau and Richard Brunell, Matt Lait, Jennifer Maisel, Cathy and Len Unger, and Nancy and Harold Zirkin offered important feedback as well. Our children—Matthew, Andrew, Annabel, and Harold—provided constant inspiration through their questions and curiosity, and left me confident that future generations will not forget the Holocaust. And my wife, Leslie, read through countless late-night revisions, when she would no doubt rather have been sleeping. She provided a font of ideas and somehow kept things together at home all the while.

My literary agent, Ronald Goldfarb, saw the potential in this project from the very beginning, while Bruce Nichols, my editor at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, shepherded the project through its various fits and starts with a keen eye and a gentle touch. My copyeditor, Melissa Dobson, put it all in final shape.

Lastly, the

New York Times

and executive editor Dean Baquet gave me the time and support to complete this project, while my 2013 fellowship at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, part of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, provided critical access to its vast archives and top-notch researchers. The museum’s mantra—“Never Again”—was a constant reminder of why this still matters.