The Nazi and the Psychiatrist (26 page)

Read The Nazi and the Psychiatrist Online

Authors: Jack El-Hai

Julius Streicher perceived “the substance taken out of an operated knee” in Card VII of the Rorschach inkblot series.

Card IX of the Rorschach inkblot test, in which Göring saw “a spook with a fat stomach.”

The portrait of Göring that the Reichsmarschall inscribed, signed, and gave to Kelley.

Kelley called Göring’s suicide an admirably defiant act against the Nuremberg prison authorities.

The young psychiatrist, soon to be a criminologist.

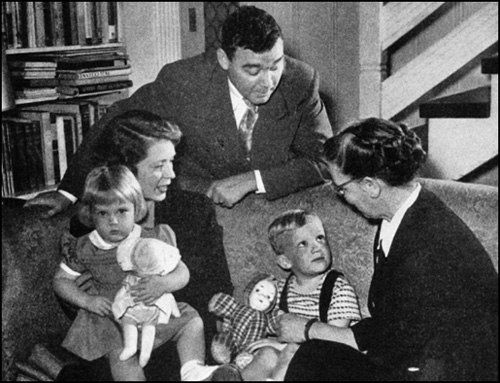

Nancy Bayley (right), a Terman Study researcher, visits Dukie and Douglas M. Kelley, with their children Alicia and Doug, in the living room of their home on Highgate Road. (Photograph by Gene Lester © 1952 SEPS licensed by Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN. All rights reserved.)

The principles of general semantics found their way into several of Kelley’s criminology courses.

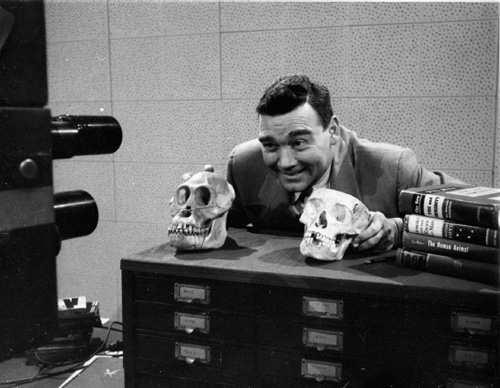

On the set of Kelley’s successful educational television series

Criminal Man

.

A

s the International Military Tribunal ran its course, questions arose about the men who had committed the atrocities and advanced the criminal regime that took shape in the evidence and testimony presented in court. Why did the Nazis and their followers do it? Were they insane? Could anyone find in them a specific mental disorder responsible for their criminal conduct? In the US House of Representatives, Congresswoman Emily Taft Douglas of Illinois raised those questions in 1945 during a committee hearing on the punishment of war criminals. Douglas doubted that Americans, or anyone else for that matter, understood much about the motivations for the enormities of which the Nazi defendants were accused. “

We don’t know about war crimes,” she said. “We don’t know at all. We know specifically of atrocities, but we do not understand the psychology of war crimes. . . . There has been a psychological sickness that has bred these crimes, which we must understand or we cannot cope with it in the future.”

At the same time, many who worked in the tribunal or observed it realized that merely punishing the guilty would not make the proceedings a success. Something more had to emerge from the months of courtroom sessions: definitive signs that Nazi Germany and its ideologies had been crushed and that the world could learn from the horrors of the previous dozen years to prevent similar catastrophes from happening. “

We have high hopes that this public portrayal of the guilt of these evildoers,” declared President Harry Truman, “will bring wholesale and permanent revulsion

on the part of the masses of our former enemies against war, militarism, aggression, and nations of racial superiority.”

Back in Dukie’s hometown of Chattanooga, Kelley had plenty to think about, much of it unconnected with the workings of Nazi minds. He “

was anxious to forget the war years and get on with new plans and projects,” Dukie later wrote, perhaps too breezily. Kelley certainly needed a job, and wanted one that would further his ambition of achieving a top academic position. He had a long-neglected wife to consider, as well as the possibility of their starting a family.

Still, Kelley’s thoughts about the Nazi leaders did not fade. In his spare hours he had written down his musings about Nazis, the basis of their evil, and the lessons of the recent war for Americans. Upon his return to the United States, “

a number of people urged him to write about his studies of the Nazis,” Dukie wrote to an acquaintance. “He was reluctant to do so because after nearly four years at war with no respite, he was tired and wanted nothing more than for us to drive around the United States and see again the countryside we both love—which we did.” But as they traveled, the book manuscript he had begun envisioning since his initial weeks in the Nazis’ company slowly took shape. Kelley could not leave his Nuremberg experience behind. Indeed, it had followed him home.

To stimulate his thinking, Kelley had papers—mountains of them. The boxes he had shipped home from Nuremberg bulged with documents, many unique. He had also shipped to Tennessee a collection of

books that their Nazi authors had signed; copies of letters he had conveyed between Hermann and Emmy Göring; a sampling of the Reichsmarschall’s paracodeine pills; X-rays of Hitler’s skull; and the wax-sealed specimens of crackers, cookies, and candies that Rudolf Hess had claimed were poisoned by his English keepers. A hoard of papers and artifacts, much of it medically intriguing or macabre, was close at hand. These materials taunted him. He wanted to make personal and professional sense of the past year of his life: experiences that countless other psychiatrists, psychologists, and academics would have done anything to have shared. Reluctantly Kelley began to sort out his own opinions on the Nazis. Now he could view them

from a distance. What could he hypothesize from the evidence of cruelty and criminality?

Looking over his Rorschach data and interpretations, Kelley could see that none of the top Nazi prisoners, except the brain-damaged Ley, showed signs of any mental illness or personality traits that would label him insane. Here he came up against wartime popular myth. All of the men, even the disordered and forgetful Hess, were responsible for their actions and capable of distinguishing right from wrong. Göring, the charmer with whom Kelley had so much in common, presented special challenges. Kelley was astonished that such a clearly intelligent and cultured man so blatantly lacked a moral compass and empathy for others. Perhaps, Göring’s example suggested, anybody with brains and weighty responsibilities—Kelley included—could lose his bearings and harm others. His intense interest in Göring was plain in the bulk of material on the Reichsmarschall he had brought back, which outweighed by far the material on any other defendant.

If Kelley had hoped to discover a Nazi “germ,” a deviant personality common to the defendants, there was little evidence of one. Instead, he found in their personalities traits that he called neuroses, not uncommon psychiatric flaws that could certainly trouble the Nazis and increase their ruthlessness, but did not put them outside the boundaries of the normal. Kelley believed that countless men like Göring, unburdened by conscience and driven by narcissism, spent their days “

behind big desks deciding big affairs as businessmen, politicians, and racketeers. . . . Shrewd, smooth, conscienceless speakers and writers like Goebbels, slick, big-time salesmen like Ribbentrop, and all the financial and legalistic hangers-on can be counted among the men whose faces we know by sight.”

His long proximity to the prisoners had convinced him that they exhibited several qualities: unbridled ambition, weak ethics, and excessive patriotism that could justify nearly any action of questionable rightness. Moreover, the Nazis, even the most elite and powerful among them, were not monsters, evildoing machines, or automata without soul and feelings. Göring’s concern for his family, Schirach’s love of poetry, and

Kaltenbrunner’s fear under stress had moved Kelley and persuaded him that his former prisoners had emotions and responses like other people. Anyone who dismissed them “

because we look with disgust and hatred upon their activities and upon their actions, to sell the Third Reich short,” was making a big mistake. Their relative normalcy left a portentous hanging question. How could their inexplicable conduct be understood? Without comprehending the Nazis or identifying their psychoses, Kelley could only reluctantly conclude that enormous numbers of people had the potential to act as the war criminals had.