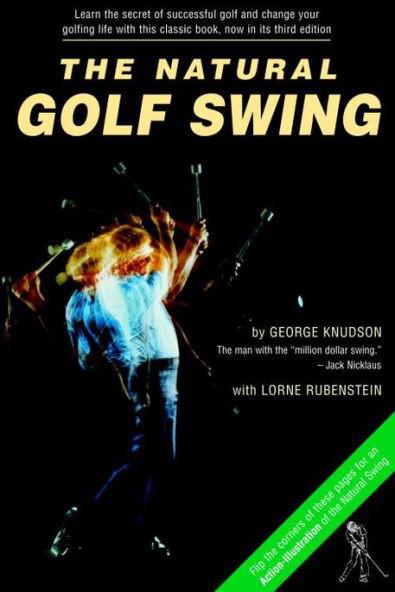

The Natural Golf Swing

Read The Natural Golf Swing Online

Authors: George Knudson,Lorne Rubenstein

Tags: #Sports & Recreation, #General

Copyright © 1988 George Knudson and Lorne Rubenstein

Illustrations Copyright © 1988 Neil Harris

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher – or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency – is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Knudson, George, 1937-1989

The natural golf swing

eISBN: 978-1-55199-482-6

1. Swing (Golf). I. Rubenstein, Lorne. II. Title.

GV979.S9K68 1988 796.3523 C88-093243-0

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporation’s Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P9

www.mcclelland.com

v3.1

BY LORNE RUBENSTEIN

I

N THE WINTER OF 1968

when I was still a teenager, I thought golf was all feel and that there was no need to learn the basics. Having achieved a fairly low handicap for a golfer who relied on feel and instinct alone, I smugly thought that nobody could teach me anything about the swing. I wasn’t willing to take the time to learn the swing, of course, but that’s another story. My idea of instruction was a quick tip in a golf magazine. If it didn’t work, I dropped it. Can’t be right, I thought.

That winter of 1968 I was very aware of what George Knudson was doing on the U.S. professional circuit. It was my custom to borrow my father’s car and drive to the corner of Bathurst St. and Lawrence Ave. in Toronto every night around nine o’clock to pick up

The Globe and Mail

and check the golf news. First came the news that Knudson had won the Phoenix Open. A week later, he had won the Tucson Open. Two in a row.

I’ll never forget my reaction the Sunday night I learned that George had won in Tucson. Since he was four shots from the lead heading into the last round, I figured he might finish well up in the list, but surely he wouldn’t win. I drove to the corner to see where he did finish.

Unable to wait until I got home, I turned the corner, stopped the car, and turned on the interior lights. There it was. Knudson had won for the second week in a row. I was ecstatic. I didn’t know George at all then, but I felt so happy for him. I also felt he’d done something worth pursuing: he had evidently gotten the best out of himself. Somehow I imagined that this was what golf was all about, and that maybe one day I too could perform to the best of my ability. George’s wins gave me confidence.

But then I had to think things over. George knew the golf swing. I had often read that he was a so-called “pure swinger.” Jack Nicklaus had said he had a million-dollar swing. Golfers I met around Toronto courses told me that Knudson swung the club better than anybody since Ben Hogan. They told me he’d studied it, and that he had it figured out.

Gradually, I came to accept that there was a lot more to a good golf swing than feel and instinct. You had to know what you were doing. Knudson knew.

Twenty years later, I feel fortunate to have gotten to know George well and to have written this book with him. When he first looked at my swing a decade ago on the range at Glen Abbey, he told me it wasn’t bad for a left-hander. Trouble was, I swing right-handed. George has helped me understand the golf swing since then. The game is so much more enjoyable for me now.

Anybody who knows George knows that he puts his heart into everything he does. He’s an inspiration to his friends and I know he’ll be an inspiration to all golfers who take the time to understand the golf swing he teaches in these pages. “Golf can be fun,” George says, and he means it. He’s a special guy, one of a kind.

P

ICTURE A KID

hitting golf balls on a practice range. He’s hitting the ball with all his strength, thrilled by the idea of going at it as hard as he can. Funny thing, though. The ball doesn’t seem to go far or straight. Hitting at the ball doesn’t seem to work. Keeping his eye on the ball, staring at it, and focusing on it so that he can make contact with it isn’t producing very satisfying shots.

That kid was me as a twelve-year-old at the St. Charles Golf and Country Club in Winnipeg, my birthplace. I worked in the backshop there, shagged balls for the pro, Les Beaven, and practised every chance I got. Practising was my thing. It got to the point where I practised one hour for every hour I was on the course. I could hardly wait to get on the range.

Like most youngsters, I was taken with the long ball. And how do you hit the long ball? Simple. You hit the ball hard. Take that club in your hands and swing it with your hands and arms as fast as you can.

But this didn’t work. I wasn’t getting anywhere. There was no consistency. I’d catch the ball solidly one time and then mis-hit it so badly the next time I could feel the vibration in the shaft through my fingers and in my arms. It didn’t make sense. Wasn’t the idea to hit the ball? And isn’t that what I was doing, trying to get the clubface squarely behind the ball at impact?

Luckily, I accidentally came across something that has informed the basis of my thinking on the swing. A giant

flagpole that stood in front of the St. Charles clubhouse caught my eye as I stood on the range. It wasn’t doing me any good glaring at the ball and trying to hit the thing, so I decided to focus my attention on the pole. It became my target. I immediately started making better golf swings and getting more satisfactory results.

My reasoning went like this. I had been slapping at the ball while

trying

to hit it. After I hit a shot I didn’t like I’d move the ball backward or forward in my stance, figuring that maybe I wasn’t catching it at the right time in my swing. Or I’d fiddle with my swing by changing the angle at which I came into the ball or messing with the way I took the club back. If it worked for a shot, I thought I had the answer. It was all trial and error and it was mostly error.

My main mistake was that I had made the ball the most important consideration. The ball was everything; that’s where I directed my concentration and energy. But it kept me from making a swing. I was hitting

at

the ball, not through it. I wasn’t making a swing. I was chopping at the ball, cutting myself off. I needed something to take my eye and mind

off the ball

. The flagpole was perfect for that purpose.

The flagpole became my target. So what if it was about five hundred yards away from where I stood on the practice tee? That was the point. I couldn’t make the ball go that far, but I could focus on a point well beyond the ball. As I look back on my thirty-five years or so of thinking about the swing, I realize that the flagpole at St. Charles had everything to do with the development of my thoughts on golf as a target game and on the swing as a motion. The flagpole became my target, not the ball.

I exchanged the idea of hitting the ball for the idea of swinging through it toward a target.

The idea was to swing in such a way that the ball would reach the apex of its flight just as it was in front of the pole, and then blot out the pole as it fell to the ground. This picture appealed to me; I loved the idea of the ball soaring into the sky, reaching its high point, and then falling to the ground down the line of the pole. I started the swing with my hands, but at least I was swinging beyond the ball.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I probably learned more about the golf swing from using that flagpole than anything that came later. It was the foundation of my conviction that golf is a game of motion directed toward a target. The ball just gets in the way. So my attention started going beyond the ball. And that’s where it still is. I began to see that the ball should be in the same place in my stance every time if I were going to make a motion through it. That would promote consistency. This all pointed to a constant ball location, though I wasn’t as clear on this back in my early days at St. Charles.

But the flagpole helped me think of the swing as a pure, uninterrupted, and uninhibited move in which I would have no sensation of a hit. It was as if I were studying karate or one of the other martial arts. I wanted to move

through

the target. I wanted to freewheel. Why should I let the ball stop the motion? Why should I let it interrupt the flow of my swing? I still feel this way. It’s just that I’ve spent the last thirty-five years refining the idea of the swing as a natural motion.

Most golfers play the game as if it requires the same considerable hand-eye coordination as found in baseball, tennis, or squash. They focus on the ball and devise ways of making contact, as if golf were basically a matter of hitting the ball. By thinking this way golfers turn the game into a hand-eye game, a hit-the-ball game. But it’s not.

Golf is a stationary ball game in which we make a motion toward a target. The ball simply gets in the way of the motion. That’s why a golfer who is properly set up to the ball and his target can make good shots while closing his eyes. I know; during an experiment I once shot 67 at Glen Abbey, the home of the Canadian Open, while closing my eyes on each swing.

Why can blind people golf, and often quite well? It’s because the ball sits still. They don’t have to react to it. An assistant or coach helps the blind golfer set up to the ball. Once he has done so, he can hit the ball quite easily. He’s in a good starting position in which he is oriented

toward his target. He knows he wants to swing toward that target and senses that he wants to finish his swing motion facing his target. So all he needs to do is find a means of connecting the starting position to the finishing position. I’ll show you how to do that.

The fact that the golf ball is stationary leads golfers to believe they must find a way to

hit

it, to get it moving. Golfers who think this way make the game more difficult than it needs to be. They out-think themselves when standing over the ball. They believe they must

make

a swing happen. It’s as if they say: “I’m going to find a way to hit that thing, if it takes my whole life.”