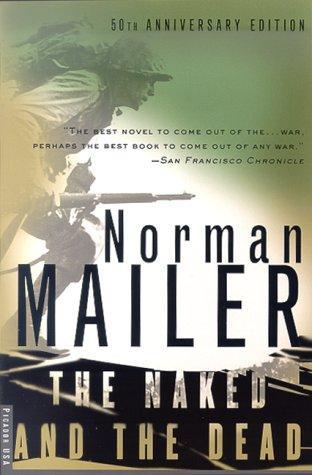

The Naked and the Dead

Read The Naked and the Dead Online

Authors: Norman Mailer

| The naked and the dead | |

| Norman Mailer | |

| New York, N.Y. : Picador/H. Holt, 1998. (1948) | |

| Rating: | ★★★★☆ |

| Tags: | Historical fiction, General, Fiction, World War; 1939-1945, Literary, War Military, War stories, Pacific Area Historical fictionttt Generalttt Fictionttt World War; 1939-1945ttt Literaryttt War Militaryttt War storiesttt Pacific Areattt |

From Library Journal

This 50th-anniversary edition of Mailer's World War II epic contains a new introduction by the author. If your current copy is falling apart, now is the time to replace it.

Copyright 1998 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Review

"The best novel to come out of the . . . war, perhaps the best book to come out of any war."—_San Francisco Chronicle_

"Best novel yet about World War II."—_Time_

"Brutal, agonizing, astonishingly thoughtful."—_Newsweek_

"Nightmarish masterpiece of realism."—_Cleveland News_

"Vibrant with life, abundant with real people, full of memorable scenes. To call it merely a great book about the war would be to minimize its total achievement."—_The Philadelphia Inquirer_

"The most important American novel since

Moby-Dick

."—_Providence Journal_

--

Review

The Naked and the Dead

by Norman Mailer

Bookflap:

A Word from the Publisher to the Reader. . .

Twenty-seven years ago I was fortunate enough to be associated with the publication of John Dos Passos' Three Soldiers. In no year since have I felt the same surge of excitement for a war novel -- not until the manuscript of Norman Mailer's

The Naked and the Dead

was readied for publication.

There is no direct parallel between the two books. The world has changed and toughened since Dos Passos wrote. The Naked and the Dead is a tougher book, one that reflects the variables that time and change have introduced. But, like its distinguished predecessor, Norman Mailer's book is essentially the story of men themselves rather than of their sometimes purposeless fighting. These men who tear their hearts out trying to capture an island from the Japanese are the product of the years they have lived. They have been formed by their wives, their sweethearts, their farms, their jobs, their colleges. To each, war has been an activating agent.

I believe you will never forget these men -- frightened men, sometimes obscene, humorous, sick, scabrous, full of yearning for home as it was, or home as it seems in memory. They are men in war, but like most of us, they do not know where they are going; they know only their own past.

Because I believe The Naked and the Dead is a great novel I can say that if you have read Thomas Boyd's

Through the Wheat

, Remarque's

All Quiet on the Western Front

, Hemingway's

Farewell to Arms

, or Three Soldiers, you cannot afford to pass by this astonishing performance by a young man who at twenty-five knows more about the core of man than many a writer of twice his years.

Stanley W. Rinehart Jr.

Rinehart & Company, Inc.

New York Toronto

Grateful thanks are expressed to the publishers and copyright owners

for permission to reprint lyrics from the following songs:

Betty Co-ed,

by Paul Fogarty and Rudy Vallee.

Copyright, 1930, by Carl Fischer, Inc., New York, and used with their permission.

Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?

Words by E. Y. Harburg, music by Jay Gorney.

Copyright, 1932, by Harms, Inc., and used with the permission of Music Publishers Holding Corporation.

Faded Summer Love,

words and music by Phil Baxter.

Copyright, 1931, by Leo Feist, Inc., and used with their permission.

I Love a Parade,

words by Ted Koehler, music by Harold Arlen.

Copyright, 1931, by Harms, Inc., and used with the permission of Music Publishers Holding Corporation.

Show Me the Way to Go Home,

words and music by Irving King.

Copyright, 1925, by Harms, Inc., and used with the permission of Music Publishers Holding Corporation.

These Foolish Things Remind Me of You,

by Jack Strachey, Hold Marvel and Harry Link.

Copyright, 1935, by Bourne, Inc., and used with their permission.

All characters and incidents in this novel are fictional, and any resemblance

to any person, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

COPYRIGHT, 1948, BY NORMAN MAILER

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY THE HADDON CRAFTSMEN, INC., SCRANTON, PA.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

I would like to thank William Raney, Theodore S. Amussen, and Charles Devlin for the aid and encouragement given me at various times in the writing of this novel.

To my Mother and Bea

PART ONE

Wave

1

Nobody could sleep. When morning came, assault craft would be lowered and a first wave of troops would ride through the surf and charge ashore on the beach at Anopopei. All over the ship, all through the convoy, there was a knowledge that in a few hours some of them were going to be dead.

A soldier lies flat on his bunk, closes his eyes, and remains wide-awake. All about him, like the soughing of surf, he hears the murmurs of men dozing fitfully. "I won't do it, I won't do it," someone cries out of a dream, and the soldier opens his eyes and gazes slowly about the hold, his vision becoming lost in the intricate tangle of hammocks and naked bodies and dangling equipment. He decides he wants to go to the head, and cursing a little, he wriggles up to a sitting position, his legs hanging over the bunk, the steel pipe of the hammock above cutting across his hunched back. He sighs, reaches for his shoes, which he has tied to a stanchion, and slowly puts them on. His bunk is the fourth in a tier of five, and he climbs down uncertainly in the half-darkness, afraid of stepping on one of the men in the hammocks below him. On the floor he picks his way through a tangle of bags and packs, stumbles once over a rifle, and makes his way to the bulkhead door. He passes through another hold whose aisle is just as cluttered, and finally reaches the head.

Inside the air is steaming. Even now a man is using the sole fresh-water shower, which has been occupied ever since the troops have come on board. The soldier walks past the crap games in the unused salt-water shower stalls, and squats down on the wet split boards of the latrine. He has forgotten his cigarettes and he bums one from a man sitting a few feet away. As he smokes he looks at the black wet floor littered with butts, and listens to the water sloshing through the latrine box. There has been really no excuse for coming, but he continues to sit on the box because it is cooler here, and the odor of the latrine, the brine, the chlorine, the clammy bland smell of wet metal is less oppressive than the heavy sweating fetor of the troop holds. The soldier remains for a long time, and then slowly he stands up, hoists his green fatigue pants, and thinks of the struggle to get back to his bunk. He knows he will lie there waiting for the dawn and he says to himself, I wish it was time already, I don't give a damn, I wish it was time already. And as he returns, he is thinking of an early morning in his childhood when he had lain awake because it was to be his birthday and his mother had promised him a party.

Early that evening Wilson and Gallagher and Staff Sergeant Croft had started a game of seven card stud with a couple of orderlies from headquarters platoon. They had grabbed the only empty place on the hold deck where it was possible to see the cards once the lights were turned off. Even then they were forced to squint, for the only bulb still lit was a blue one near the ladder, and it was difficult to tell the red suits from the black. They had been playing for hours, and by now they were in a partial stupor. If the hands were unimportant, the betting was automatic, almost unconscious.

Wilson's luck had been fair from the very beginning, but after one series in which he had taken three games in a row it had become phenomenal. He was feeling very good. There was a stack of Australian pound notes scattered sloppily and extravagantly under his crossed legs, and while he felt it was bad luck to count his money, he knew he must have won nearly a hundred pounds. It gave him a thick lustful sensation in his throat, the kind of excitement he received from any form of abundance. "Ah tell ya," he announced to Croft in his soft southern voice, "this kind of money is gonna be the ruination of me yet. Ah never will be able to figger out these goddam pounds. The Aussies work out everythin' backwards."

Croft gave no answer. He was losing a little, but, more annoying, his hands had been drab all night.

Gallagher grunted scornfully. "What the hell! With your kind of luck you don't have to figure your money. All you need is an arm to pick it up with."

Wilson giggled. "That's right, boy, but it's gonna have to be a mighty powerful arm." He laughed again with an easy, almost childish glee and began to deal. He was a big man about thirty years old with a fine mane of golden-brown hair, and a healthy ruddy face whose large features were formed cleanly. Incongruously, he wore a pair of round silver-rimmed glasses which gave him at first glance a studious or, at least, a methodical appearance. As he dealt his fingers seemed to relish the teasing contact of the cards. He was daydreaming about liquor, feeling rather sad because with all the money he had now, he couldn't even buy a pint. "You know," he laughed easily, "with all the goddam drinkin' Ah've done, Ah still can't remember the taste of it unless Ah got the bottle right with me." He reflected for a moment, holding an undealt card in his hand, and then chuckled. "It's just like lovin'. When a man's got it jus' as nice and steady as he wants it, well, then he never can remember what it's like without it. And when he ain't got it, they ain't nothin' harder than for him to keep in mind what a pussy feels like. They was a gal Ah had once on the end of town, wife of a friend of mine, and she had one of the meanest rolls a man could want. With all the gals Ah've had, Ah'll never forget that little old piece." He shook his head in tribute, wiped the back of his hand against his high sculptured forehead, brought it up over his golden pompadour, and chuckled mirthfully. "Man," he said softly, "it was like dipping it in a barrel of honey." He dealt two cards face down to each man, and then turned over the next round.

For once Wilson's hand was poor, and after staying a round because he was the heavy winner, he dropped out. When the campaign was over, he told himself, he was going to drum up some way of making liquor. There was a mess sergeant over in Charley Company who must have made two thousand of them pounds the way he sold a quart for five pounds. All a man needed was sugar and yeast and some of them cans of peaches or apricots. In anticipation he felt a warm mellow glow in his chest. Why, you could even make it with less. Cousin Ed, he remembered, had used molasses and raisins, and his stuff had been passing decent.

For a moment, though, Wilson was dejected. If he was going to fix himself any, he would have to steal all the makings from the mess tent some night, and he'd have to find a place to hide it for a couple of days. And then he'd need a good little nook where he could leave the mash. It couldn't be too near the bivouac or anybody might be stumbling onto it, and yet it shouldn't be too far if a man wanted to siphon off a little in a hurry.

There was just gonna be a lot of problems to it, unless he waited till the campaign was over and they were in permanent bivouac. But that was gonna take too long. It might even be three or four months. Wilson began to feel restless. There was just too much figgering a man had to do if he wanted to get anything for himself in the Army. Gallagher had folded early in that hand too, and was looking at Wilson with resentment. It took somebody like that dumb cracker to win all the big pots. Gallagher's conscience was bothering him. He had lost thirty pounds at least, almost a hundred dollars, and, while most of it was money he had won earlier on this trip, that did not excuse him. He thought of his wife, Mary, now seven months pregnant, and tried to remember how she looked. But all he could feel was a sense of guilt. What right did he have to be throwing away money that should have been sent to her? He was feeling a deep and familiar bitterness; everything turned out lousy for him sooner or later. His mouth tightened. No matter what he tried, no matter how hard he worked, he seemed always to be caught. The bitterness became sharper, flooded him for a moment. There was something he wanted, something he could feel and it was always teasing him and disappearing. He looked at one of the orderlies, Levy, who was shuffling the cards, and Gallagher's throat worked. That Jew had been having a lot of goddam luck, and suddenly his bitterness changed into rage, constricted in his throat, and came out in a passage of dull throbbing profanity. "All right, all right," he said, "how about giving the goddam cards a break. Let's stop shuffling the fuggers and start playing." He spoke with the flat ugly "a" and withered "r" of the Boston Irish, and Levy looked up at him, and mimicked, "All right, I'll give the caaads a break, and staaart playing."