The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (29 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

A new type, imported from Greece, first appeared in Palestine in the seventh century. The form consisted of two parts: (a) a true nozzle (spout) that terminated with the wick hole; and (b) a round, open saucer. The nozzle was fully enclosed, like a short tube, which the potter attached to the saucer. By the fourth century the sides of the saucer had “closed up” on top to form a large filling hole, one through which the oil was poured. The Greek lamp nozzle was distinctively elongated (

Illus.4.2:2

). Palestine was flooded during the Persian Period with imports of this kind. Early Greek potters continued to fashion lamps out of two parts (nozzle and body), but eventually potters began working from a single piece.

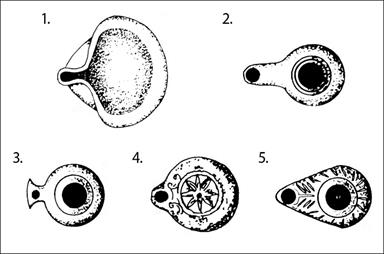

Illus.4.2

. Typical Palestinian

oil lamps.

1. Late Iron age 2. Hellenistic 3. Bow-spouted (“Herodian”)

4. Roman 5. Byzantine

The closed lamp afforded room for decoration, especially on the top surface, called the

discus

. Imported lamps could be highly decorated. However, Palestinian lamps were generally less so, commensurate with the Jewish commandment forbidding any “graven image, or manner of likeness” (Ex 20:4–5). We shall see that decorated oil lamps did come into vogue after the destruction of the Second Temple. But their ornamentation is comparatively restrained, avoids depiction of the living creatures altogether, and consists of geometrical patterns, fruit, olive branches, and the like.

At first oil lamps were hand-made, then wheel-made, and finally mould-made. From II BCE onwards almost all oil lamps were mould-made. This type of lamp was fashioned from upper and lower moulds which at first were virtually identical. A thin layer of clay was applied between the moulded halves to fuse them. A wick hole and filling hole were then cut into the top, and the lamp was finally fired in a kiln.

The bow-spouted (“Herodian”) oil lamp

Of particular interest for our purposes is a lamp type well known in Palestine during the first and early second century CE. It had several varieties, and is most immediately recognized by a distinctively bowed spout or nozzle (

Illus.4.2:3

). A number of these lamps have been found in the Nazareth basin. Though it is often termed “Herodian,” this designation—as with the tomb of the same name (see above)—is a misnomer. We shall shortly see that this lamp type was not contemporary with the reign of Herod the Great, and that it outlived his dynasty. Perhaps realizing this, Paul Lapp used an alternate name for this lamp in his classification,

[374]

one which we adopt in these pages: the bow-spouted lamp.

At least nineteen bow-spouted oil lamps have been found at Nazareth.

[375]

There are probably many more, represented by small shards. “With some rare exceptions,” writes Bagatti, “the lamps came to us in fragments.”

[376]

Naturally, fragments do not always permit a clear typological determination, and therefore some smaller fragments have not been used in my tally.

[377]

Nineteen is probably a conservative estimate for the total number of these lamps.

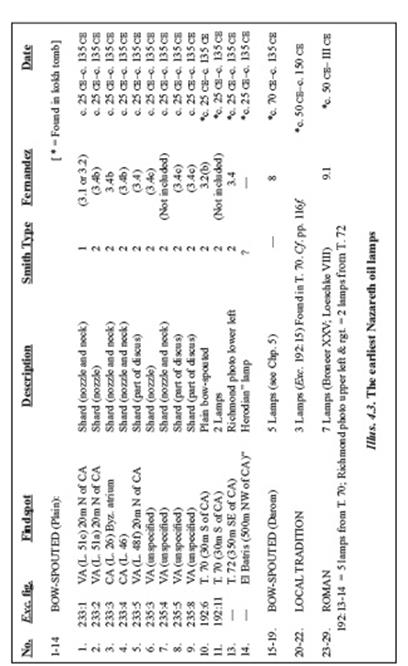

Fourteen of the Nazareth bow-spouted lamps are made on the potter’s wheel and are quite plain, with very little (or no) ornamentation. The type is often called “Herodian,” and the Nazareth examples are itemized in

Illus

.

4.3

, numbers 1–14. The remaining five bow-spouted lamps belong to a distinctive variety which appeared briefly between the two Jewish revolts.

[378]

Called Darom (“Southern”) by Varda Sussman,

[379]

this subtype is mould-made and decorated, with a number of characteristics not shared by its plainer cousin (

pre-70

Appendix 5).

For a long time, scholars had only the vaguest notion of the dating of the bow-spouted oil lamp. In 1914, H. Walters dated its appearance in Palestine to IV–III BCE, through false association with Greek and Hellenistic lamps

[380]

—thus erring by several centuries. In the 1920s and 30s G. Fitzgerald maintained that the bow-spouted lamp was a type “common in the Hellenistic Period, but which is also well-known in Byzantine times.” He dated some specimens as early as III BCE.

[381]

A decade later it became evident that the type appeared in Early Roman times. Hence the name “Herodian.”

[382]

However, studies in Israel since mid-century, and an increasing fund of published parallels—often in carefully controlled stratigraphic contexts—have inexorably moved the

terminus post quem

for this lamp later and later. In 1961 P. Lapp wrote that undecorated bow-spouted lamps were current “75 B.C.–A.D. 70.”

[383]

In that same year, however, R. Smith tentatively dated the type from

c

. 37 BCE (the accession of Herod the Great). Smith even considered a later beginning for this lamp possible.

[384]

He offered the following explanation of the designation:

The name “Herodian,” originally intended to designate the period of the reign of Herod the Great (37 to 4 B.C.), seems to have been used as a Palestinian equivalent for the term “Augustan.” The narrow use-span of the lamp which the term originally implied cannot be maintained, but the term “Herodian” is still useful if we take it to include the period of the entire Herodian dynasty, which ended with the death of Herod Agrippa II in presumably A.D. 100.

[385]

This view is now also out of date. In 1976, Yigael Yadin noted that the bow-spouted lamp was not found in a representative I BCE assemblage in Jerusalem. Yadin estimated its appearance there to “the middle of [Herod’s reign

or even later

”

[386]

(emphasis added). In 1980 J. Hayes wrote that such lamps were common in Jerusalem in early I CE.

[387]

In 1982 Varda Sussman dated the appearance of this type in Judea to “the reign of Herod.” A few years later, however, she was able to conclude: “Recent archaeological evidence suggests that their first appearance was somewhat later,

after the reign of Herod

”

[388]

(emphasis added). We will adopt the latter view in these pages.

Thus, we can now date the first appearance of the bow-spouted lamp in Jerusalem to

c

. 1–25 CE.

[389]

Because a few years must be allowed for the spread of the type to the rural villages of the north,

c

. 15–

c

. 40 CE is the earliest probable time for the appearance of this type in Southern Galilee. Accordingly, we shall adopt 25 CE as the

terminus post quem

for the bow-spouted oil lamp at Nazareth.

Use of these lamps continued for over a century, and specialists are unanimous that they were in use until 135–150 CE.

[390]

“For practical purposes,” writes Smith, “…we may take A.D. 135 as the

terminus ante quem

” for this type of lamp.

[391]

The time span, then, for the bow-spouted lamp in Lower Galilee is slightly over a century:

c

. 25 CE to

c

. 135 CE.

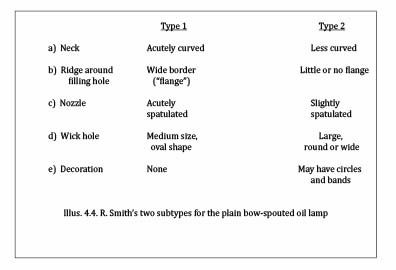

In 1961 R. Smith published a study of the plain bow-spouted (“Herodian”) lamp of Palestine. He attempted to differentiate two subtypes. The earlier variety—which we shall call Type 1—went out of fashion in the middle of I CE. At that time, a related Type 2 appeared, first in Jerusalem and then throughout the land.

[392]

Smith identifies five characteristics that differentiate these two subtypes,

[393]

as listed in

Illus

.

4.4

.

Twelve of the earliest Nazareth lamps are Type 2, which according to Smith postdates

c

. 50 CE. Only one lamp is Type 1 and

may

predate 50 CE by a few years.

[394]

Thus, we see that virtually all the oil lamps at Nazareth postdate mid-I CE, as do the tombs. The convergence of tomb evidence and oil lamp evidence makes it amply clear that—per Smith’s typology, at any rate—the entire evidentiary profile for Roman Nazareth is post-50 CE. Only a single outlier (one oil lamp)

might

date a few years earlier, but no other evidence from the emerging settlement could be dated so early.

[395]

The above having been said, it bears mention that Smith’s typology is not universally recognized. Thus, Rosenthal and Sivan write in 1978:

There have been attempts by Kahane (1961) and Smith

(1961) to divide the Herodian

lamps into chronological and typological groups. The latest excavations, however, seem to indicate that all the variations occur simultaneously.

[396]

If Rosenthal and Sivan are correct, then the outlier

[397]

is contemporaneous with the remaining plain bow-spouted lamps, and

all

of those lamps (nos. 1–14 in

Ilus

. 3) may date as late as 135 CE or as early as 25 CE. This moves the

terminus post quem

back a quarter century.

In conclusion, the data clearly show that settlers did not come into the basin before

c

. 25 CE. In the “early” scenario, a few people entered the basin in the second quarter of I CE and began building tombs about mid-century.

On the other hand, the evidence equally supports a “late” scenario, whereby people came into the Nazareth basin not before the beginning of the second century CE. After all, the

terminus ante quem

for the nineteen bow-spouted Nazareth lamps is

c

. 135 CE.

[398]

Both scenarios—early and late—satisfy the 85 to 110-year time span during which people must have settled the basin.

[399]

Of course, these are extremes. The totality of evidence cannot be arbitrarily weighted towards the earliest or towards the latest possible date. More probable—indeed, most probable—is a “middle” scenario which equally credits the late and early views: people started to come into the Nazareth basin towards the midpoint of this time span. In other words, our best hypothesis—judging from the tombs and from the earliest datable Roman evidence at Nazareth—is that settlers started to come into the basin about 80 to 90 CE.