The Mystery of Olga Chekhova (19 page)

Read The Mystery of Olga Chekhova Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #History, #General, #World, #Europe, #Military, #World War II, #Modern, #20th Century

Olga’s sister, Ada, went to Brussels to stay with the newly married couple a month later, in January 1937. Reading between the lines of Ada’s letter to Aunt Olya in Moscow, all was not well with the marriage from the start. One suspects that Marcel Robyns had simply wanted to acquire a trophy wife, while Olga had sought security away from the hectic world of Babelsberg. All she found was a sense of claustrophobia. From being the central figure in the Knipper matriarchy in Berlin, she suddenly found herself expected to play a very subsidiary role entertaining his boring business associates.

The apartment on the Avenue des Nations in Brussels was very modern in the Art Deco style. Even the dining plates were made out of black glass. Yet Olga lacked her ‘own little corner, where one could sit cosily’. The couple had four servants and, in true Belgian style, the food was munificent. ‘There are always people in the house—all of them businessmen. Conversations are in French, German, English, Dutch, Flemish, and Russian.’ Ada now had very mixed feelings about her new brother-in-law. ‘He is a very good and decent man, looks extremely well, very pampered, but he is a hard, dry businessman. One feels quite uneasy in his company, and somehow it’s not comfortable here in spite of all the external beauty. Olga cheered up when I arrived. She wants to go to Berlin with me for a couple of weeks - she is better off there.’

Marcel Robyns came as often as he could to Berlin to bask in the reflected glory of his wife, especially during the great success of her role in the play Der

Blaufuchs (The Blue Fox).

Olga’s friends dubbed him ‘Herr Tschechowa’ behind his back. She and her family began to be increasingly irritated by his presence. He then brought his own family to stay at Olga’s apartment at 74 Kaiserdamm.

‘We have had guests staying for three weeks,’ Ada wrote to Aunt Olya. ‘Olga’s husband, his mother, and his daughter with a governess. We had to employ a cook, and I slept in a corner in Mother’s room, Olga was feeling nervous and always escaped from the house, as every evening she is performing, with a stunning success, in Der

Blaufuchs

. The theatre is always full, Olga is spoken about as a remarkable actress. And our Belgians have turned the whole household upside down. To make things worse, Maman [Robyns] does not speak a word of German, and Marcel is afraid to go out on his own. It’s a mystery to me why Olga married him, as she has to pay for everything with her own money.’

Another thought crossed Ada’s mind. ‘I’ve been thinking that maybe you don’t really want to receive letters from us any more,’ she wrote in the same letter. The show trials in the Soviet Union and the atmosphere of Stalinist xenophobia had been reported in the German press. It would not be long before the two sides of the Knipper family, the German and the Russian, would be split by greater events.

15. The Great Terror

It may seem strange that the Knipper family correspondence between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union should have been able to continue until the end of 1937. But there can be little doubt that the NKVD was far more thorough in its censorship of letters and the examination of parcels than the remarkably idle Gestapo.

Olga Chekhova had clearly enjoyed playing ‘the American uncle’ with her presents from abroad in the early 1930s. She had sent her young cousin Vova (the son of her Uncle Vladimir) a series of gifts: a German alphabet when he was a baby, then a sweater, then a suit. Finally, she sent him a gnome with eyes which lit up with a crackle when you pressed a button. She also sent Lev’s son, Andrei, a sailor suit, as if the Tsarist fashion for dressing children remained de

rigueur

in the Soviet Union.

Vova asked his father who had sent him the gnome. ‘Papa flew into a fury and talked loudly for a long time, saying that they were going mad in Germany.’ He showed Vova a photograph of a beautiful woman wearing a white summer dress and told him that she was his cousin and an actress in the movies. Vova’s father then hid the gnome and the photograph of Olga Chekhova in the bottom drawer of his desk and ordered Vova not to say anything to anybody about the present or about the members of the family in Germany. The Knippers in Moscow had been getting increasingly nervous since 1934. They were not only of German origin, they were also members of the closely watched artistic community.

The dragooning of artists for political purposes in the Soviet Union involved measures against any recalcitrants. Action against ‘counter-revolutionary writers’ who rejected Socialist Realism began comparatively gently, then intensified along with the Great Terror of 1937 and 1938.

During the night of 16 May 1934, soon after the poet Anna Akhmatova reached the apartment of Osip and Nadezhda Mandelstam, three OGPU operatives burst in. (The OGPU became the NKVD two months later.) They examined every scrap of paper and took every book to pieces. The object of their search was a copy of a poem about Stalin which Mandelstam had recited to friends. One of them must have been an informer. The OGPU officers never found the poem, but Mandelstam was forced to write it out for them at the Lubyanka, with the introductory confession: ‘I am the author of the following poem of a counter-revolutionary nature.’ Its most dangerous line referred to Stalin’s ‘large laughing cockroach eyes’.

At first Mandelstam was sent into internal exile. Perhaps Stalin did not want to attract too much controversy. But a second arrest and condemnation to the labour camps left him, a sick man, with no hope of survival. He died on 27 December 1938 in a transit camp outside Vladivostok. He was buried in a mass grave for Gulag prisoners. In a final, unintentional insult, the NKVD even spelt the writer’s name wrong on the death certificate.

The event which provided the rationale for Stalin’s purges took place on 1 December 1934 when Sergei Kirov, the chief of the Communist Party in Leningrad, was assassinated. This was Stalin’s equivalent of the Reichstag fire. All civil liberties, notional though they had been already, were suspended. The NKVD started to work night and day as the witch-hunt against Trotskyist saboteurs widened to include almost anyone with foreign contacts. Soviet authorities later admitted that between 1935 and 1940, 19 million people were arrested, of whom over 7 million died, either in the Gulag or by execution.

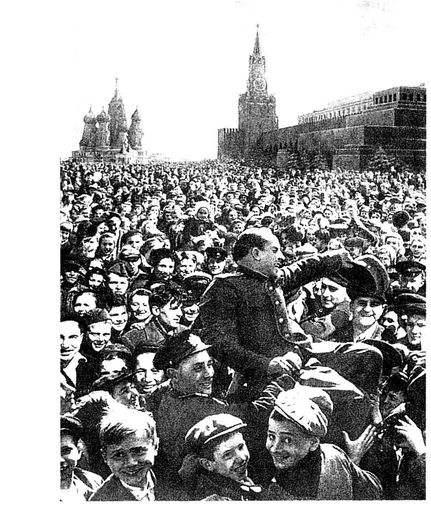

I .Victory celebrations in Red Square, 9 May 1945

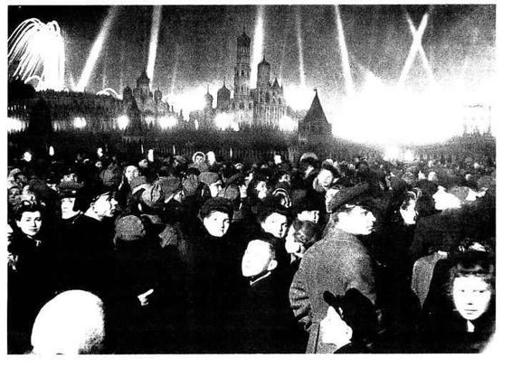

2. The searchlights and fireworks of victory night, 9 May 1945.

3. Anton Chekhov reading

The Seagull

to the Moscow Art Theatre. 1898: (rear left) Nemirovich-Danchenko; (central group) Olga Knipper-Chekhova (Aunt Olya), Stanislavsky. Chekhov and Lilina (Stanislavsky’s wife): (far right) Meyerhold.

4. Stanislavsky. Gorky and Lilina. Yalta. 1900.

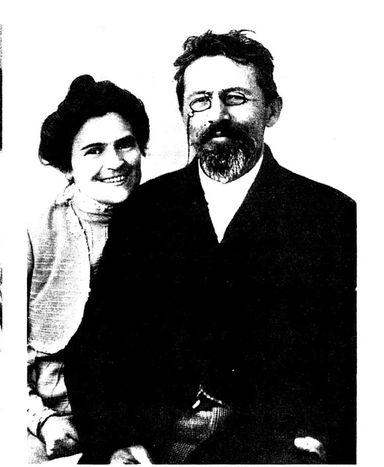

5. Anton Chekhov and Olga Knipper-Chekhova.

6.

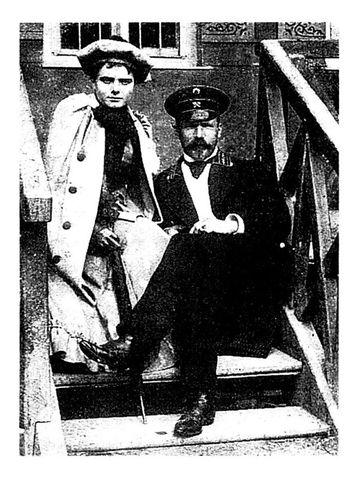

Konstantin and Lulu Knipper in the Caucasus soon after their marriage.