The Myst Reader (55 page)

Authors: Robyn Miller

THE JOURNEY HOME WAS UNEVENTFUL. MAKING

good time, Anna arrived at the Lodge just after dawn. She had been away, in all, seven days.

Leaving the cart in the deep shadow by the ridge, she climbed up onto the bridge and tiptoed across, meaning to surprise her father, but the Lodge was empty.

Anna returned to the doorway and stood there, looking out over the silent desert.

Where would he be? Where?

She knew at once. He would be at the circle.

Leaving the cart where it was, she headed east across the narrow valley, climbing the bare rock until she came out into the early sunlight. It made sense that he would go there at this hour, before the heat grew unbearable. If she knew him, he would be out there now, digging about, turning over rocks.

Her father’s illness had driven the circle from her mind for a time, but coming back from Tadjinar, she had found herself intrigued by the problem.

It seemed almost supernatural. But neither she nor her father believed in things that could not be explained.

Everything

had a rational reason for its existence.

Coming up onto the ridge, Anna saw her father at once, in the sunlight on the far side of the circle, crouched down, examining something. The simple physical presence of him there reassured her. Until then she had not been sure, not

absolutely

sure, that he was all right.

For a time she stood there, watching him, noting how careful, how methodical he was, enjoying the sight of it enormously, as if it were a gift. Then, conscious of the sun slowly climbing the sky, she went down and joined him.

“Have you found anything?” she asked, standing beside him, careful not to cast her shadow over the place where he was looking.

He glanced up, the faintest smile on his lips. “Maybe. But not an answer.”

It was so typical of him that she laughed.

“So how was Amanjira?” he said, straightening up and turning to face her. “Did he pay us?”

She nodded, then took the heavy leather pouch from inside her cloak and handed it to him. “He was pleased. He said there might be a bonus.”

His smile was knowing. “I’m not surprised. I found silver for him.”

“Silver!”

He hadn’t told her. And she, expecting nothing more than the usual detailed survey, had not even glanced at the report she had handed over to Amanjira. “Why didn’t you say?”

“It isn’t our business. Our business is to survey the rocks, not exploit them.”

She nodded at the pouch. “We make our living from the rock.”

“An honest day’s pay for an honest day’s work,” he answered, and she knew he meant it. Her father did not believe in taking any more than he needed. “Enough to live” was what he always said, begrudging no one the benefit from what he did.

“So how are you?” she asked, noting how the color had returned to his face.

“Well,” he answered, his eyes never leaving hers. “I’ve come out here every morning since you left.”

She nodded, saying nothing.

“Come,” he said suddenly, as if he had just remembered. “I have something I want to show you.”

They went through the gap between two of the converging ridges, then climbed up over a shoulder of rock onto a kind of plateau, a smooth gray slab that tilted downward into the sand, like a fallen wall that has been half buried in a sandstorm.

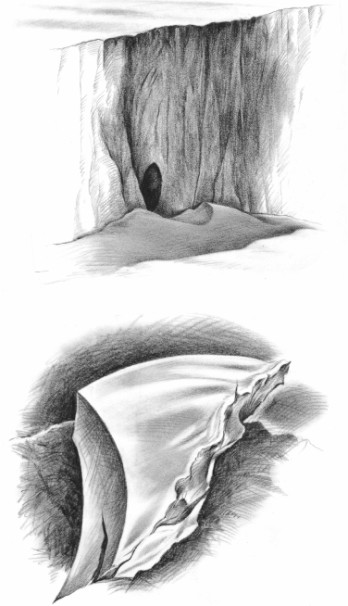

Across from them another, larger ridge rose up out of the sand, its eroded contours picked out clearly by the sun. The whiteness of the rock and the blackness of its shadowed irregularities gave it the look of carved ivory.

“There,” he said, pointing to one of the larger patches of darkness near the foot of the ridge.

“A cave?” she asked, intrigued.

“A tunnel.”

“Where does it lead?”

“Come and see.”

They went down, crossing the hot sand, then ducked inside the shadowed entrance to the tunnel. They stopped a moment, letting their eyes grow accustomed to the darkness after the brilliant sunlight outside, then turned, facing the tunnel. Anna waited as her father lit the lamp, then held it up.

“Oh!”

The tunnel ran smoothly into the rock for fifteen, twenty paces, but that was it. Beyond that it was blocked by rock fall.

Undaunted, her father walked toward it, the lamplight wavering before him. She followed, examining the walls as she went.

“It looks lavatic,” she said.

“It is,” he answered, stopping before the great fall of rock. “And I’d say it runs on deep into the earth. Or would, if this rock wasn’t in the way.”

Anna crouched and examined a small chunk of the rock. One side of it was smooth and glassy—the same material as the walls. “How recent was this fall?” she asked.

“I can only guess.”

She looked up at him. “I don’t follow you.”

“When I found no answers here, I began to look a bit wider afield. And guess what I found?”

She shrugged.

“Signs of a quake, or at least of massive earth settlement, just a few miles north of here. Recent, I’d say, from the way the rock was disturbed. And that got me thinking. There was a major quake in this region thirty years back. Even Tadjinar was affected, though mildly. It might explain our circle.”

“You think so?”

“I’d say that the quake, the rockfall here, and the circle are all connected. How, exactly, I don’t yet know. But as I’ve always said to you, we don’t know everything. But we might extend our knowledge of the earth,

if

we can get to the bottom of this.”

She smiled. “And the surveys?”

He waved that away. “We can do the surveys. They’re no problem. But this … this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, Anna! If we can find a reason for the phenomena, who knows what else will follow?”

“So what do you suggest?”

He gestured toward the fallen rock. “I suggest we find out what’s on the other side of that.”

AFTER THEY HAD EATEN, ANNA UNPACKED THE

cart. She had bought him a gift in the Jaarnindu Market. As she watched him unwrap it, she thought of all the gifts he had bought her over the years, some practical—her first tiny rock hammer, when she was six—and some fanciful—the three yards of bright blue silk, decorated with yellow and red butterflies that he had brought back only last year.

He stared at the leather case a moment, then flicked the catch open and pushed the lid back.

“A chess set!” he exclaimed, a look of pure delight lighting his features. “How I’ve missed playing chess!” He looked to her. “How did you know?”

Anna looked down, abashed. “It was something you said. In your sleep.”

“When I was ill, you mean?”

She nodded.

He stared at the chessboard lovingly. The pieces—hand-carved wood, stained black and white—sat in their niches in two tiny wooden boxes.

It was not a luxury item by any means. The carving was crude and the staining basic, yet that did not matter. This, to him, was far finer than any object carved from silver.

“I shall begin to teach you,” he said, looking up at her. “Tonight. We’ll spend an hour each night, playing. You’ll soon get the hang of it!”

Anna smiled. It was just as she’d thought.

Gifts

, she recalled him saying,

aren’t frivolous things, they’re very necessary. They’re demonstrations of love and affection, and their “excess” makes life more than mere drudgery. You can do without many things, Anna, but not gifts, however small and insignificant they might seem.

So it was. She understood it much better these days.

“So how are we to do it?”

He looked to her, understanding at once what she meant. Taking one of his stone hammers from the belt at his waist he held it up. “We use these.”

“But it’ll take ages!”

“We have ages.”

“But …”

“No buts, Anna. You mustn’t be impatient. We’ll do a little at a time. That way there’ll be no accidents, all right?”

She smiled and gave a single nod. “All right.”

“Good. Now let me rest. I must be fresh if I’m to play chess with you tonight!”

IN THE DAYS THAT FOLLOWED, THEIR LIVES

fell into a new routine. An hour before dawn they would rise and go out to the tunnel, and spend an hour or two chipping away at the rockfall. Anna did most of this work, loathe to let her father exhaust himself so soon after his illness, while he continued his survey of the surrounding area. Then, as the sun began to climb the desert sky, they went back to the Lodge and, after a light meal, began work in the laboratory.

There were samples on the shelves from years back that they had not had time to properly analyze, and her father decided that, rather than set off on another of their expeditions, they would catch up on this work and send the results to Amanjira.

Late afternoon, they would break off and take a late rest, waking as the sun went down and the air grew slowly cooler.

They would eat a meal, then settle in the main room at the center of the Lodge to read or play chess.

Anna was not sure that she liked the game at first, but soon she found herself sharing her father’s enthusiasm—if not his skill—and had to stop herself from playing too long into the night.

When finally he did retire, Anna stayed up an hour or so afterward, returning to the workroom to plan out the next stage of the survey.

No matter what her father claimed, she knew Amanjira would not be satisfied with the results of sample analyses for long. He paid her father to survey the desert, and it was those surveys he was interested in, not rock analysis—not unless those analyses could be transformed somehow into vast riches.

In the last year they had surveyed a large stretch of land to the southwest of the Lodge, three days’ walk away in the very heart of the desert. To survive at all out there they needed to plan their expeditions well. They had to know exactly where they could find shelter and what they would need to take. All their food, water, and equipment had to be hauled out there on the cart, and as they were often out there eight or ten days, they had to make provision for sixteen full days.

It was not easy, but to be truthful, she would not have wanted any other life. Amanjira might not pay them their true worth, but neither she nor her father would have wanted any other job.

She loved the rock and its ways almost as much as she loved the desert. Some saw the rock as dead, inert, but she knew otherwise. It was as alive as any other thing. It was merely that its perception of time was slow.

On the eighth day, quite early, they made the breakthrough they had been hoping for. It was not much—barely an armhole in the great pile of rock—yet they could shine a light through to the other side and see that the tunnel ran on beyond the fall.

That sight encouraged them. They worked an extra hour before going back, side by side at the rock face, chipping away at it, wearing their face masks to avoid getting splinters in their eyes.

“What do you think?” he said on the walk back. “Do you think we might make a hole big enough to squeeze through, then investigate the other side?”

Anna grinned. “Now who’s impatient?”