The Myst Reader (2 page)

Authors: Robyn Miller

What did you see, Atrus?

I saw …

He saw the one with the knifelike face turn to his camel and, reaching across the ornate and bulging saddlebag, take a small cloth sack from within a strange, hemispherical wicker basket. The sack seemed to move and then settle.

Atrus adjusted his glasses, certain that he had imagined that movement, then looked again, in time to see his grandmother place the sack upon the pile of other things she’d bartered for. For a brief while longer he watched, then, when it showed no sign of moving, looked to his grandmother.

Anna stood facing the eldest of the traders, her gaunt yet handsome face several shades lighter than his, her fine gray hair tied back into a bun at the nape of her neck. The hood of her cloak was down, as was his, their heads exposed to the fierce, late afternoon heat, but she did not seem to mind. Such she did deliberately, to convince the traders of her strength and self-reliance. Yes, and suffered for it, too, for even an hour out in that burning sun was more than enough, not to speak of the long walk back, laden down with heavy sacks of salt and flour and rolls of cloth, and other items she’d purchased.

And he lay here, hidden, impotent to help.

It was easier, of course, now that he could help her tend the garden and repair the walls, yet at times like this he felt torn—torn between his longing to see the caravan and the wish that his grandmother did not have to work so hard to get the things they needed to survive.

She was almost done now. He watched her hand over the things she’d grown or made to trade—the precious herbs and rare minerals, the intricately carved stone figures, and the strange, colorful iconic paintings that kept the traders coming back for more—and felt a kind of wonder at the degree of her inventiveness. Seven years he had lived with her now; seven years in this dry and desolate place, and never once had she let them go hungry.

That in itself, he knew, was a kind of miracle. Knew, not because she had told him so, but because he had observed with his own lensed eyes the ways of this world he inhabited, had seen how unforgiving the desert was. Each night, surviving, they gave thanks.

He smiled, watching his grandmother gather up her purchases, noting how, for once, one of the younger traders made to help her, offering to lift one of the sacks up onto her shoulder. He saw Anna shake her head and smile. At once the man stepped back, returning her smile, respecting her independence.

Loaded up, she looked about her at the traders, giving the slightest nod to each before she turned her back and began the long walk back to the cleft.

Atrus lay there, longing to clamber down and help her but knowing he had to stay and watch the caravan until it vanished out of sight. Adjusting the lenses, he looked down the line of men, knowing each by the way they stood, by their individual gestures; seeing how this one would take a sip from his water bottle, while that one would check his camel’s harness. Then, at an unstated signal, the caravan began to move, the camels reluctant at first, several of them needing the touch of a whip before, with a grunt and hoarse bellow, they walked on.

Atrus?

Yes, grandmother?

What did you see?

I saw great cities in the south, grandmother, and men—so many men …

Then, knowing Anna would be expecting him, he began to make his way down.

AS ANNA ROUNDED THE GREAT ARM OF ROCK

, coming into sight of the cleft, Atrus walked toward her. Concealed here from the eyes of the traders, she would normally stop and let Atrus take a couple of the sacks from her, but today she walked on, merely smiling at his unspoken query.

At the northern lip of the cleft she stopped and, with a strange, almost exaggerated care, lowered the load from her shoulder.

“Here,” she said quietly, aware of how far voices could travel in this exposed terrain. “Take the salt and flour down to the storeroom.”

Silently, Atrus did as he was told. Removing his sandals, he slipped them onto the narrow ledge beneath the cleftwall’s lip. Chalk marks from their lesson earlier that day covered the surface of the outer wall, while close by a number of small earthenware pots lay partly buried in the sand from one of his experiments.

Atrus swung one of the three bone-white sacks up onto his shoulder, the rough material chafing his neck and chin, the smell of the salt strong through the cloth. Then, clambering up onto the sloping wall, he turned and, crouching, reached down with his left foot, finding the top rung of the rope ladder.

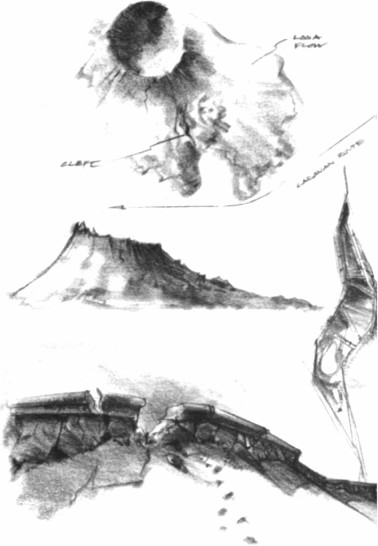

With unthinking care, Atrus climbed down into the cool shadow of the cleft, the strong scent of herbs intoxicating after the desert’s parched sterility. Down here things grew on every side. Every last square inch of space was cultivated. Between the various stone and adobe structures that clung to them, the steep walls of the cleft were a patchwork of bare red-brown and vivid emerald, while the sloping floor surrounding the tiny pool was a lush green, no space wasted even for a path. Instead, a rope bridge stretched across the cleft in a zigzag that linked the various structures not joined by the narrow steps that had been carved into the rock millennia before. Over the years, Anna had cut a number of long troughlike shelves into the solid walls of the cleft, filling them with earth and patiently irrigating them, slowly expanding their garden.

The storeroom was at the far end, near the bottom of the cleft. Traversing the final stretch of rope bridge, Atrus slowed. Here, water bubbled up from an underground spring, seeping through a tilted layer of porous rock, making the ancient steps wet and slippery. Farther down a channel had been cut into the rock, directing the meager but precious flow across the impermeable stone at the bottom of the cleft into the natural depression of the pool. Here, too, was the place where his mother was buried. At one end of it lay a small patch of delicate blue flowers, their petals like tiny stars, their stamen velvet dark.

After the searing heat of the desert sand, the coolness of the damp stone beneath his feet was delightful. Down here, almost thirty feet below the surface, the air was fresh and cool, its sweet scent refreshing after the dryness of the desert outside. There was the faintest trickling of water, the soft whine of a desert wasp. Atrus paused a moment, lifting the heavy glasses onto his brow, letting his pale eyes grow accustomed to the shadow, then went on down, ducking beneath the rock overhang before turning to face the storeroom door, which was recessed into the stone of the cleftwall.

The surface of that squat, heavy door was a marvel in itself, decorated as it was with a hundred delicate, intricate carvings; with fish and birds and animals, all of them linked by an interwoven pattern of leaves and flowers. This, like much else in the cleft, was his grandmother’s doing, for if there was a clear surface anywhere, she would want to decorate it, as if the whole of creation was her canvas.

Raising his foot, Atrus pushed until it gave, then went inside, into the dark and narrow space. Another year and he would need to crouch beneath the low stone ceiling. Now, however, he crossed the tiny room in three steps; lowering the sack from his shoulder, he slid it onto the broad stone shelf beside two others.

For a moment he stood there, staring at the single, bloodred symbol printed on the sack. Familiar though it was, it was a remarkably elaborate thing of curves and squiggles, and whether it was a word or simply a design he wasn’t sure, yet it had a beauty, an elegance, that he found entrancing. Sometimes it reminded him of the face of some strange, exotic animal, and sometimes he thought he sensed some kind of meaning in it.

Atrus turned, looking up, conscious suddenly of his grandmother waiting by the cleftwall, and chided himself for being so thoughtless. Hurrying now, stopping only to replace his glasses, he padded up the steps and across the swaying bridge, emerging in time to see her unfasten her cloak and, taking a long, pearl-handled knife from the broad leather toolbelt that encircled her waist, lean down and slit open one of the bolts of cloth she’d bought.

“That’s pretty,” he said, standing beside her, adjusting the lenses, then admiring the vivid vermilion and cobalt pattern, seeing how the light seemed to shimmer in the surface of the cloth, as in a pool.

“Yes,” she said, turning to smile at him, returning the knife to its sheath. “It’s silk.”

“Silk?”

In answer she lifted it and held it out to him. “Feel.”

He reached out, surprised by the cool, smooth feel of it.

She was still looking at him, an enigmatic smile on her lips now. “I thought I’d make a hanging for your room. Something to cheer it up.”

He looked back at her, surprised, then bent and lifted one of the remaining sacks onto his shoulder.

As he made his way down and across to the storeroom, he saw the rich pattern of the cloth in his mind and smiled. There was a faint gold thread within the cloth, he realized, recalling how it had felt: soft and smooth, like the underside of a leaf.

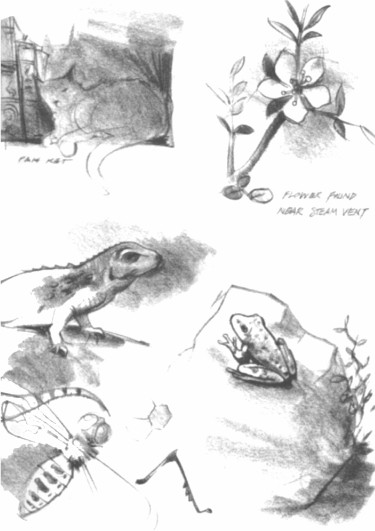

Depositing the second sack, he went back. While he was gone, Anna had lifted the two bolts of cloth up onto the lip of the cleftwall, beside the last of the salt and flour sacks. There was also a small green cloth bag of seeds, tied at the mouth with a length of bloodred twine. Of the final sack, the one he’d thought had moved, there was no sign.

He frowned, then looked to his grandmother, but if she understood his look, she didn’t show it.

“Put the seeds in the kitchen,” she said quietly, lifting the bolt of silk onto her shoulder. “We’ll plant them tomorrow. Then come back and help me with the rest of the cloth.”

As he came back from the storeroom, he saw that Anna was waiting for him on the broad stone ledge at the far end of the garden. Even from where he stood he could see how tired she was. Crossing the rope bridge to the main house, he went quickly down the narrow steps that hugged the wall and, keeping carefully to the smooth, protruding rocks that delineated the pool’s western edge, crouched and, taking the metal ladle from its peg, leaned across and dipped it into the still, mirrorlike surface.

Standing again, he went swiftly along the edge, his toes hugging the rock, careful not to spill a drop of precious water, stopping beside the ledge on which Anna sat.

She looked up at him and smiled; a weary, loving smile.

“Thank you,” she said, taking the ladle and drinking from it, then offered it back.

“No,” he said softly, shaking his head. “You finish it.”

With a smile, she drained the ladle and handed it back.

“Well, Atrus,” she said, suddenly relaxed, as if the water had washed the tiredness from her. “What did you see?”

He hesitated, then. “I saw a brown cloth sack, and the sack moved.”

Her laughter was unexpected. Atrus frowned, then grinned as she produced the sack from within the folds of her cloak. It was strange, for it seemed not to hold anything. Not only that, but the cloth of the sack was odd—much coarser than those the traders normally used. It was as if it had been woven using only half the threads. If it had held salt, the salt would have spilled through the holes in the cloth, yet the sack held something.