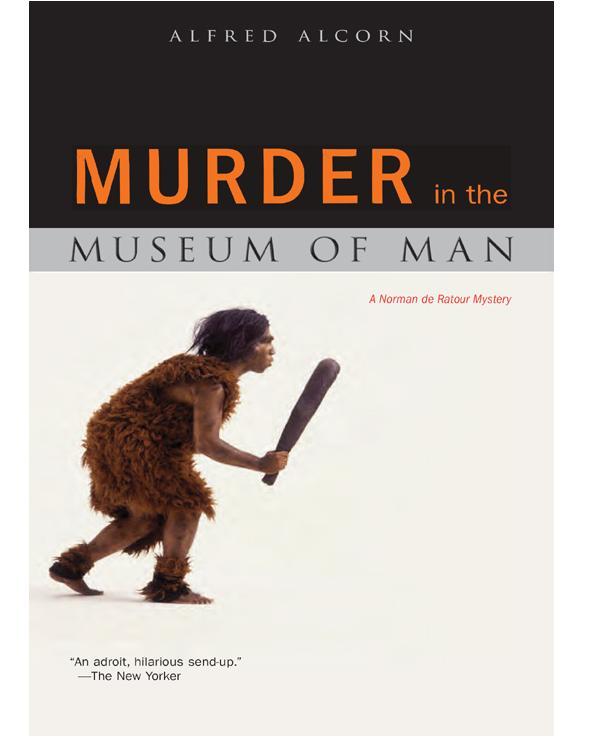

The Murder in the Museum of Man

Read The Murder in the Museum of Man Online

Authors: Alfred Alcorn

Copyright © 1997, 2009 by Alfred Alcorn

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

First published in 1997 by Zoland Books, Cambridge, Massachusetts

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to:

Steerforth Press L.L.C., 45 Lyme Road, Suite 208

Hanover, New Hampshire 03755

The Library of Congress cataloged the hardcover edition of this book as follows:

Alcorn, Alfred.

Murder in the Museum of Man / Alfred Alcorn. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58195-236-0

I. Title.

PS3551.L29M87 1977

813′.54—dc20 96-37558

CIP

This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

v3.1

For Margaret and Sarah

The following account by Norman A. de Ratour, constituting unofficial entries into the Log of the Museum of Man, was entered as evidence in Middling County Superior Court, and while in the public domain as such, is reprinted here with the consent and cooperation of the author.

FRIDAY, MARCH 27

It is with great relief and some reluctance that I begin these unauthorized and unofficial entries into the Log of the Museum of Man. I say “reluctance” because, as Recording Secretary here at the MOM for more than three decades now (if you count the nearly year and a half I was assistant to the ailing Miss Vogel before her retirement), I have endeavored to be meticulously objective in my maintenance of the official and authorized records. In these thirty-odd years I have heard no more than one or two complaints about the minutes of the innumerable meetings I have kept. No one has ever questioned the Annual Report that I submit to the Board of Governors or the way I have organized the records and the biographical files or my editorship of the

MOM Quarterly

, a publication that began at my instigation when Dr. Commer became director. But matters of late have taken such a turn that no “official” record will do them justice. I refer, of course, to the strange and disquieting disappearance of Dean Cranston Fessing. A one- or two-day absence is one thing, but the good dean has been gone now for a week, and concern is mounting for his well-being. Moreover, I find the dean’s absence symptomatic of a deeper malaise afflicting the Museum of Man. We are like some great crippled beast about which the scavengers

have gathered. In a manner breathtaking in its boldness, Wainscott University is attempting nothing less than to take us over, lock, stock, and barrel. Of a piece with these dark happenings is Malachy Morin’s usurpation of nearly all executive power at this venerable institution.

Before I go any further, however, I want to make it clear that I have no intention of letting this

ex officio

journal (which I plan to keep under separate code in the mainframe memory and the printouts in a locked drawer of my desk) degenerate into a mere compendium of complaints about Mr. Morin. Above all, I do not wish to sound querulous. (I would like to point out, incidentally, that I am making this entry after hours, on my own time, when the last lingering visitor has left this marvelous place to me and old Mort, the key-jangling security guard. And, of course, to Damon Drex, whom I can hear five floors down cavorting with his charges in the Primate Pavilion.) No, I am determined not to be reduced, in this ad hoc journal, merely to venting my frustration with that man. But the fact remains that Malachy (“call me Mal”) Morin has lately made my life here at the MOM nothing less than hellish. His offenses are so legion I scarcely know where to begin.

With effort I have been able, just, to abide the man’s presumptuous familiarity, his jockstrap jocularity, his calling me, with that laugh of his, Bow Tie to my face and Stick behind my back. And it’s not just his larger-than-life person and persona, his six feet, six inches and four hundred pounds or thereabouts of corporeality, much of it soft lard that bulges everywhere. It is not even his questionable grooming and the peculiar acridity in which he billows about this place. After all, keeping that much flesh clean on a regular basis must be something of a chore, particularly for someone who is by nature slovenly. It is not even the way, starting as Dr. Commer’s executive assistant, he took advantage of that aging scholar’s infirmities, machinating his way

around the Board of Governors, making a mockery of the Rules of Governance with his so-called executive committee, which he stacked with his cronies from the Wainscott jockocracy — to drag in a suitably clumsy portmanteau word — until, as Administrative Director, the reach of his meaty hands knows no bounds. (Even as I write, the hoots and howls of chimpanzees rise from the new exercise yard that Damon Drex had built at great and controversial expense in the old courtyard, which used to be graced by an ancient rhododendron and some prim lilacs, a development, quite frankly, that Malachy Morin should have prevented rather than encouraged.)

But it is not even that. It is not even that he had no right whatsoever to appoint me “press assistant” for the MOM, thereby loading on me a spate of spurious duties, telling me that I should simply tape all of the pertinent proceedings in the museum for the record. The fact is — and these rules have yet to be officially altered — I still report directly to the Board of Governors. And for good reason. With all due respect to Dr. Commer and his distinguished predecessors, the position of Recording Secretary was established at the very founding and incorporation of the museum as a distinctly independent office in order, and I quote, “that the Board of Governors as constituted above should have on an annual basis and at such other times as deemed appropriate clear and objective accounts of all important undertakings of the museum and its officers.” Nothing could be less equivocable. The fact is, as Recording Secretary, I report to no one but the Board of Governors, to the institution, and, in my own small way, to history.

But how, I ask you (you being the intrepid researcher, the field archaeologist of archives, who a hundred years from now will no doubt ferret out these little addenda), am I to fulfill my responsibilities as Recording Secretary, how am I ever to write an edifying history of this unique institution when, as “press assistant,” I

must speak to one insistent journalist after another about the apparent disappearance of Dean Fessing? About the attempt of Wainscott University to swallow us up. About the restoration of Neanderthal Hall and the diorama of Paleolithic life Professor Pilty is so determined to create there. About the rumors issuing from the Genetics Lab; about why the Primate Pavilion is not open to the public. About the rise in the price of admission; about the greenhouse effect. About the destiny of the human species. I am not exaggerating. It’s quite extraordinary how journalists think everything is their business. One impudent young man of the modern type with rimless spectacles, hair slicked back, and an oversized overcoat, was so bold as to ask me about Dean Fessing’s sexual preferences. I responded, rather wittily I think now, that I was sure he had some. Another one, the science reporter for some television station or another, asked me if dinosaurs will be included in the diorama of Stone Age life. No, I said, but perhaps a journalist or two. Such invincible ignorance.

The fact is I have never refused in all the time I have been here to provide reporters and others with what I know about the history and operation of the museum. But I was not even asked if I wanted to “handle” the press. Malachy “Stormin’ ” Morin (he’s famous, of course, for blocking that last-minute field goal attempt by Middlebrough in the “game of the century”) merely summoned me to his office last week and said I was to take press calls because I knew the place “inside out.” Naturally, I remonstrated with him, implying that as Administrative Director he should know the institution at least as well as I, that he should, when necessary and in Dr. Commer’s stead, represent the MOM to the public. “You’re it, Bow Tie,” he said. “You’re our front man. I want you to take the heat.” Take the heat. The man is a veritable fount of clichés. And he finds my seriousness risible.

Oh dear, I’m afraid I’m off on precisely the complaining note I wanted to avoid. Because in some ways it’s not even these faults of

his that I find ultimately noisome. It’s not even the man’s sexual incontinence, the way he leers after anything in a skirt, the way he importunes with his bulging eyes, the knack he has of divining just how far he can go, which women will not only tolerate his more flagrant advances but (ghastly thought) submit to them. Even that is forgivable and, quite frankly, none of my business, except where it reflects on the museum. We all have our foibles, after all.

What is not excusable, what rankles to the marrow, what is intolerable, is that Malachy Morin cares not one whit for this institution as an institution. The man is sublimely oblivious to the grandeur all around him. He could as easily be running a mortuary supply warehouse or a laundry. His eyes visibly glaze over when, on an obligatory tour for important visitors, we pause by, say, the pre-Columbian exhibit with the marvelous sitting figures from Oaxaca or the wonderful terra-cotta figurines in our admittedly small Greco-Roman display. The Solomon Islands canoe in the Oceanic exhibit with its majestic bow points and shellwork along the gunwales leaves him cold. The Hominid Collections on display in Neanderthal Hall, charting the miracle of human evolution from Lucy to Albert Einstein, are for Mr. Morin little more than a jumble of old bones. Once, to my acute embarrassment, when we were showing our extensive collection of Paleolithic coprolites to a touring delegation from Romania, he picked up one of the larger and better-formed specimens (which is strictly forbidden by museum regulations) and said, believe it or not, “talk about shitting a brick.” The Genetics Lab, of course, is utterly beyond his ken, a maze of rooms filled with serious people about whose work he has scarcely a clue. And doesn’t want one. His ignorance is

willed

. He is very nearly proud of it. Indeed, the only part of the museum he finds congenial is the Primate Pavilion, where he gladly leads important visitors, where he mugs at the monkeys and talks to

Henry, the old gorilla. And the beasts respond, as though recognizing one of their own. (Speaking of which, I am definitely going to lodge a complaint about Damon Drex and his hooting chimps. It’s like hearing the echoes of the bestiality from which we have so painfully evolved.) It is that ignorance, that obliviousness to the palpable evidence of man’s capacity, nay, instinctive compulsion, to create beauty, that I find intolerable. It’s an awful thing to say, but Malachy Morin’s very presence desecrates this temple.