The Müller-Fokker Effect (5 page)

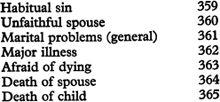

The first letter, from a cancer patient, was easy. Marilyn carried it to the row of automated typewriters and ran one unvarnished nail down the list of items posted on the wall:

Afraid of dying, then. She punched 363 on the control panel, rolled a sheet of letterhead in the typewriter and carefully typed the salutation:

‘Dear Mrs Dale:’

From there on it was simply a matter of switching from

MAN

to

AUTO

. The letter was typed in just under six seconds.

Dear Mrs Dale:

I received and read, your letter, and I was deeply touched by it. You seem to be afraid of dying. This is only natural, for no creature on God’s earth wants to die. For the humble animals, death is an end.

But not for you.

FOR YOU, DEATH IS THE VERY BEGINNING.When Columbus set sail, he didn’t know…

And so it went, right on down to the PS about remembering God in your will. A marvelous machine. Marilyn didn’t understand how the signers could refer to it as a ‘tripewriter’.

The signers were young bible students who saw no conflict between afternoons reading theology and mornings falsifying Billy’s signature to thousands of letters. They were a flippant, cynical bunch, and Marilyn hated taking letters in to them. One in particular, a fair-haired, blue-eyed, disgustingly handsome boy named Jim.

‘I understand perfectly,’ said the architect. ‘Everything modern but nothing extreme.’ He and Billy were looking at a sketch entitled

South Elevation: Bibleland

. ‘Now, about the mechanical figures and so on?’

Billy flipped through his desk diary. ‘I’ve got my computer man, Jerry, coming in Wednesday—let’s all have lunch. How much do you need to know?’

‘Everything, sir, everything. Each pavilion must be a container for the thing contained, neither more nor less. For less

is

more, and function designs its form. There must be balance, adaptability, total harmony and standardization…’

‘Now what about the site?’

‘I prefer to pick a flat, undistinguished piece of land and landscape it, Mr Koch.’

‘Okay, but keep the estimate in mind, Archy. And I wish you’d just call me Billy.’

‘Very well—Billy. I will not exceed the estimate, you can be sure. And I leave no detail to chance.

‘That’s something I learned at architecture school in my homeland. My mathematics master used to mark a problem completely wrong if there were even the slightest error. I asked him why I should lose all credit for a simple misplaced decimal point.

‘He said, “Wrong is wrong, Ögivaal. When you will be an architect, and your building collapses, it will not matter the reason. You cannot then say ‘This thirty should be a three.’ ” I never forgot his words.’

‘This site…’

‘Ah yes. I have one tentative site located, quite ideal but for the fact that it is a small Indian reservation.’

Billy’s pale blue eyes flicked up, then back to the plan. ‘If it’s worth it, we can probably get them moved off. Is it?’

‘Yes, yes, it is perfect. Quite near that place—what is the name? Death Valley.’

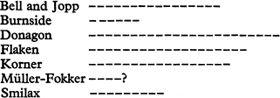

On the wall above Donagon’s desk was a histogram showing who was where in the Nobel race:

The one who really worried him was Muller-Fokker, who might have done it already. If he had really defected—no one seemed to know for sure—he might have the entire resources of Soviet research at his disposal.

Donagon wiped his damp hands, opened the journal and began just after the ripped-out pages:

We decided not to abandon the attempt after all; to try once more to store a man digitally. The last obstacle had been removed, i.e., storage. Previously we had estimated many thousands of miles of magnetic tape would be required, with complex retrieval problems. The multiple storage paired redundancy tapes, developed by Müller-Fokker (the so-called ‘Müller-Fokker tapes’) in Vienna and demonstrated by him at the Louisville National Laboratory, were exactly what we needed. These reduced our tape requirements to four ten-inch reels.

The M-F tape is much of a mystery except to its inventor. The principle seems to be

Gestalt

analysis (if that is the term), or recognition of large patterns in large amounts of data. Data fed in is not immediately recorded, but ‘comprehended’ and compressed—by the tape itself—into formulae. The tape is not magnetic but electrochemical. It may not be erased, but new data may be recorded upon old. There seems to be a layering or—We do not really understand the M-F tape at all, but we do understand it will do the job. At present we have no way of retrieving what we want from the tape, and since its inventor has vanished, it may take us many years—

Many years—

Every datum will be recorded many times, to reduce error. At present, surgeons are removing tissue samples from the subject (from bones, organs, glands, etc.) and determining cell-structure data. We have already encoded a DNA map, photographs, holographs, x-rays, resin casts, EKG’s and so on—as complete an analysis of the subject as we can make .There remains but one step, the mapping of all electrical and chemical activity of the subject’s brain. The press will be invited to this session; they will see us succeed or fail.

Succeed or fail.

Through the partition dividing his office from that of Major Fouts, he could hear the crinkle of cellophane and foil, and the sound of devouring.

The laboratory looked like a throne room. Bob sat in the throne, a surgical chair; his courtiers wore rubber gloves and his crown was a steel vise. Above the crown those in the visitors’ room could see pinkish-gray, crumpled velvet.

Back of the throne was a large illuminated map of this velvet surface on which men marked the current weather in Bob’s brain. On either side were ranks of cabinets in decorator colors. Two featured control panels, one a typewriter, two more the inevitable banks of flashing lights. Four were dialling twin reels of tape (one with some excitement), eight others were anonymous, one was vomiting paper, and the two in the visitors’ room were opened to display whiskey and glasses.

There were other press facilities in the visitors’ room, including telephones, free cigarettes, sharpened pencils and fresh pads, and a big stack of xeroxed press releases.

The one reporter who did show up had a hell of a time.

‘I sure appreciate this,’ be said to Donagon. ‘I’ll bet the rest of the gang haven’t got it this good down there in Florida.’

He asked Donagon if he’d ever heard of the magazine he worked for,

LIFE.

‘Florida?’

‘Yeah, everyone else went down to cover the big cancer cure story. I missed the plane, so I thought I might as well drop over and check this one out. I really had another assignment over by North Platte, I had to get a picture of this deformed bull. I’d take some shots of your set-up here, only I can’t. My camera and stuff caught the plane.’

He wanted Donagon to have a drink with him and hear the anecdote, but the biophysicist was wanted elsewhere.

A voice behind Bob asked him what he felt.

‘I feel…my right foot…’

‘Yes?’

‘Oh, you know how it is with workbooks.’

‘And now?’

‘A strawberry, all glowing with starry lenses, a starberry…recapitulation of the plot of some old man…buns, for instance…’

Major Fouts stood watching from half-way across the room, where Donagon manned a bank of switches. Between them and the operation was a forced-air curtain to maintain sterility. It was strange to see a man talking away with half his head sawed off and a group of surgeons peering and probing within. It made Fouts feel the sharpness of his own foot-bones.

‘This is a buckle collection…this is supposed to be a father…bank statements or…Is there anyone here named General Motors?’ In an altered voice Bob delivered a message of hope to the motor corporation.

‘Is this guy in any danger?’ Fouts whispered.

‘None at all. Shhh.’ Donagon threw more switches. A kind of phonograph arm beside the chair swung around, lowered its needle, and began to ‘play’ the brain.

‘What’s that?’

‘Shh. Nothing.’

‘Marge!’ Bob shouted. ‘As a strawberry blonde…history as a garbage truck…Now look! I’m not going to say it again…this is lumpy.’ He wept.

‘Now what do you feel?’

‘My picture in the atlas…the strawberries are…funny how the old school holds up…the old Lion Oil Company…arrested!…I hear you think…’

He sang a few bars of something no one could identify.

‘There’s an old saying around here: please wash hands before returning to work…a man disappears, but his ghost…he had it, he paid the death…in the movie freeze rabbit…U.S. Grant, the truth experiment…attaches…the bank hath changed its bank…the railroad egg trial…Dixie cups full of penetrating truth, remember?…smell that?’

‘What do you feel like now?’

‘I feel like picking my nose.’

‘You

are

picking your nose. What…?’

The door slammed back and four men walked in. Donagon rushed to meet them.

‘You’ll have to go into the visitors’ room,’ he said, smiling.

‘No we don’t.’

‘I—what? Which paper are you from?’

‘This one.’ The tallest man hauled out an old revolver and slapped him with it.

Fouts jumped to the alarm button. When the bell went off, the other three strangers pulled their guns.

‘Okay, fat boy, where are they?’

‘Where are what?’

‘The nigger-babies! The test tubes!’

One of the intruders drove the surgeons away from Bob. ‘Aw, Wes, look! Jesus Christ, they cut this guy’s head open!’

The one with the big greasy pompadour leveled his gun at Fout’s belt. ‘How about it, Fats? This one of your nigger expeermints?’

‘I don’t know what the hell you’re talking about. But I do know you’re gonna do a stretch in Leavenworth, pal. Better lay down the sidearms and make it a short visit.’

‘I think…I think I hear a bell,’ Bob volunteered.

‘I know your kind,’ said the pompadour. ‘Tryin’ to put a nigger brain into that pore mother!

Come on, boas, let’s mess up the place!’

He wheeled and fired a shot into the nearest memory cabinet.

‘I smell a shot…’ said Bob, still picking his nose.

Fout’s auto-destruct mechanism worked almost perfectly. The tape-reader charge misfired, but the other three went off as planned, as soon as one of the unauthorized persons tried to yank open a cabinet.

One charge was in the main memory bank. One was in the control console. They rendered the computer completely useless to Wes Davis and the Mud Flats Ramblers.

The third, slightly bigger charge was embedded in the soft padding of Bob’s chair, at about ear level. The chair had been designed by an orthopedic surgeon to maintain posture and reduce fatigue. What was left of it still looked good that evening, to the cleanup crew.

‘That’s the way I’d like to go,’ one remarked. ‘Comfy.’

Lieutenant Colonel Fouts tried to shut out the screaming and wailing from the other side of the partition; he tried to order his thoughts.

There was plenty to think about: The government had pulled out of the Mud Flats project and abandoned the attempt to tape a man. National Arsenamid was expected to follow suit. In retrospect, the idea did smell of circle-squaring and perpetual motion, he had to admit. So if Donagon couldn’t take the disappointment and

KNOCK OFF THAT NOISE

, it only underlined how crazy he was. The Army had kept his leaky dream afloat long enough. Anyway, National Arse would probably find something else for Donagon to do. Design a new cornflake, say, or answer the telephone.