The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses (50 page)

Read The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses Online

Authors: Kevin Birmingham

BOOK: The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce’s Ulysses

13.9Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

And yet what’s remarkable about Joyce’s novel is that it surpasses all of the disputes and dissections. It is, as Nabokov said, “a divine work of art and will live on despite the academic nonentities who turn it into a collection of symbols or Greek myths.” After ninety years in print,

Ulysses

sells roughly one hundred thousand copies a year. It has been translated into more than twenty languages, including Arabic, Norwegian, Catalan and Malayalam. There are two Chinese translations. Groups of readers gather in houses and pubs to read and discuss

Ulysses

together, and as unusual as that is for a decades-old book, the life of

Ulysses

is even more vibrant than that.

Ulysses

sells roughly one hundred thousand copies a year. It has been translated into more than twenty languages, including Arabic, Norwegian, Catalan and Malayalam. There are two Chinese translations. Groups of readers gather in houses and pubs to read and discuss

Ulysses

together, and as unusual as that is for a decades-old book, the life of

Ulysses

is even more vibrant than that.

Every year, on June 16, people around the world gather to celebrate Bloomsday. They dress like Stephen, Molly and Leopold Boom. They eat kidneys for breakfast and gorgonzola sandwiches with burgundy for lunch. They reenact scenes, sing songs featured in

Ulysses

(there are hundreds) and carouse in makeshift Nighttowns. Revelers savor Joyce-inspired art, poetry, dance, film and drama—Melbourne held a mock trial of Joyce in 2002. There have been Bloomsday celebrations in Tokyo, Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Santa Maria, Brazil, has been celebrating for twenty years straight. Two hundred cities in sixty countries have celebrated Joyce’s novel. There is no other literary event like it. One day each year, fiction creeps into reality as people around the world reenact events that never happened.

Ulysses

(there are hundreds) and carouse in makeshift Nighttowns. Revelers savor Joyce-inspired art, poetry, dance, film and drama—Melbourne held a mock trial of Joyce in 2002. There have been Bloomsday celebrations in Tokyo, Mexico City and Buenos Aires. Santa Maria, Brazil, has been celebrating for twenty years straight. Two hundred cities in sixty countries have celebrated Joyce’s novel. There is no other literary event like it. One day each year, fiction creeps into reality as people around the world reenact events that never happened.

One Leopold Bloom, wearing his bowler and black mourning suit, remembers New Yorkers greeting him on the 1 train going uptown. “Yo, Bloom, Happy Bloomsday.” Since 1982, actors have gathered in New York’s Symphony Space to perform readings that can last as long as sixteen hours (the backstage celebration, fueled with beer donated by the city’s oldest Irish pub, lasts just as long). Before Molly takes the stage at roughly eleven at night, an organizer warns the audience listening on public radio stations across the country that they should gird themselves for explicit language. Then a single actress takes the stage and reads the “Penelope” episode until nearly two in the morning as drowsy spectators—cab drivers, travel agents, people who have never read

Ulysses

and people who have studied it for years—listen to the river of Molly Bloom’s thoughts in the darkened auditorium.

Ulysses

and people who have studied it for years—listen to the river of Molly Bloom’s thoughts in the darkened auditorium.

Bloomsday’s Mecca is, of course, Dublin. The first Bloomsday celebration, in 1954, involved five men who assigned themselves roles and planned to track the novel’s events around the city in two horsedrawn carriages. The commemoration was abandoned halfway through when the group somehow ended up in a pub

not

featured in

Ulysses

. By the 1970s the crowds of people following Bloom’s footsteps began to stop traffic. In 2004 the James Joyce Centre served breakfast to ten thousand people. Gentlemen in hats and striped blazers, women in frilly collars and ankle-length dresses, crowded onto the stairs winding up to the Sandycove Tower’s parapet so they could hear the early morning exchanges between Stephen Dedalus and Buck Mulligan. One year, celebrants re-created Paddy Dignam’s funeral in the “Hades” episode with a horsedrawn hearse and a corpse played by one of Joyce’s grandnephews. On the way to Glasnevin Cemetery, he popped out of the casket to check their progress and terrified onlooking schoolchildren. Amid the hilarity, the hearse clipped a curb as it rounded the cemetery’s corner and cast everyone out, the living and the dead.

not

featured in

Ulysses

. By the 1970s the crowds of people following Bloom’s footsteps began to stop traffic. In 2004 the James Joyce Centre served breakfast to ten thousand people. Gentlemen in hats and striped blazers, women in frilly collars and ankle-length dresses, crowded onto the stairs winding up to the Sandycove Tower’s parapet so they could hear the early morning exchanges between Stephen Dedalus and Buck Mulligan. One year, celebrants re-created Paddy Dignam’s funeral in the “Hades” episode with a horsedrawn hearse and a corpse played by one of Joyce’s grandnephews. On the way to Glasnevin Cemetery, he popped out of the casket to check their progress and terrified onlooking schoolchildren. Amid the hilarity, the hearse clipped a curb as it rounded the cemetery’s corner and cast everyone out, the living and the dead.

It’s tempting to think of

Ulysses

as a book about how feeble life has become in the modern era. The warrior King of Ithaca is reduced to a lonely, cuckolded ad salesman, and the defiant genius who penned the novel was reduced to a rueful figure tapping his cane down foreign city streets. Even the censorship of the book demonstrates how an arduous work of art can be scuttled by the cursory glance of a government functionary—the writing takes place over the course of years, and the ban takes place before lunch. Censoring a book is easy. It merely requires increasing the risk of publication enough to make it too much of a gamble for a publisher, and publishing a book is already almost quixotic. One of the paradoxes of the printed word is that whatever strength and durability it has is inseparable from this inherent weakness. Even a book like

Ulysses,

we consider essential to our cultural heritage book, might never have happened—might have ended in a New York police court or with the outbreak of a world war—if it were not for a handful of awestruck people. Joyce’s novel, with its intricacies and schoolboy adventures, with each measured and careful page, gave them what it gives us: a way to sally forth into the greater world, to walk out into the garden, to see the heaventree of stars as if for the first time and affirm, against the incalculable odds, our own diminutive existence. It is the fragility of our affirmations—no matter how indecorous they may be—that makes them so powerful.

Ulysses

as a book about how feeble life has become in the modern era. The warrior King of Ithaca is reduced to a lonely, cuckolded ad salesman, and the defiant genius who penned the novel was reduced to a rueful figure tapping his cane down foreign city streets. Even the censorship of the book demonstrates how an arduous work of art can be scuttled by the cursory glance of a government functionary—the writing takes place over the course of years, and the ban takes place before lunch. Censoring a book is easy. It merely requires increasing the risk of publication enough to make it too much of a gamble for a publisher, and publishing a book is already almost quixotic. One of the paradoxes of the printed word is that whatever strength and durability it has is inseparable from this inherent weakness. Even a book like

Ulysses,

we consider essential to our cultural heritage book, might never have happened—might have ended in a New York police court or with the outbreak of a world war—if it were not for a handful of awestruck people. Joyce’s novel, with its intricacies and schoolboy adventures, with each measured and careful page, gave them what it gives us: a way to sally forth into the greater world, to walk out into the garden, to see the heaventree of stars as if for the first time and affirm, against the incalculable odds, our own diminutive existence. It is the fragility of our affirmations—no matter how indecorous they may be—that makes them so powerful.

When Joyce was a little boy and dessert time was announced, he would make his way down the staircase, holding his nursemaid’s hand, and call out to his parents with every accomplished step, “Here’s me! Here’s me!”

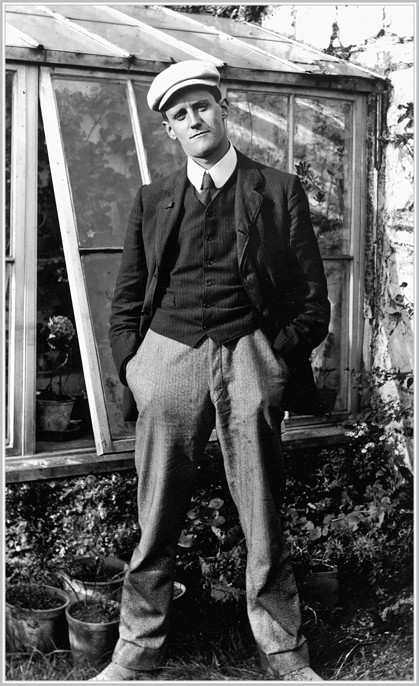

James Joyce in Dublin, 1904.

Nora Barnacle in 1904, the year she left Ireland with Joyce despite his refusal to marry her.

Ulysses

takes place on June 16, 1904, the day they had their first date.

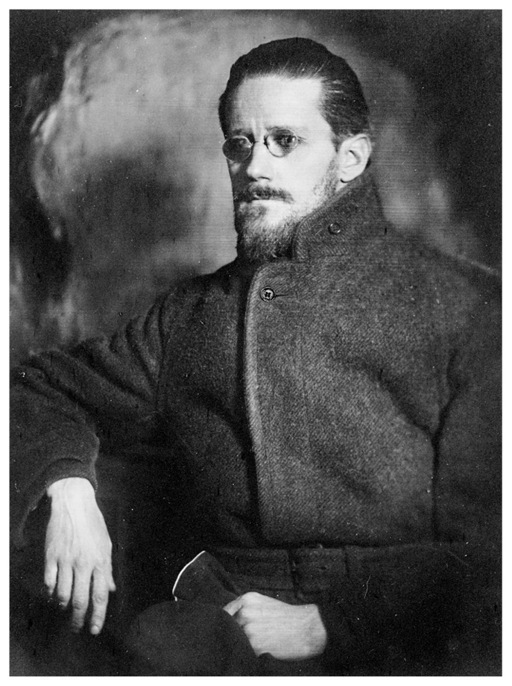

James Joyce in 1919. Some of the women in Zürich called him “Herr Satan.”

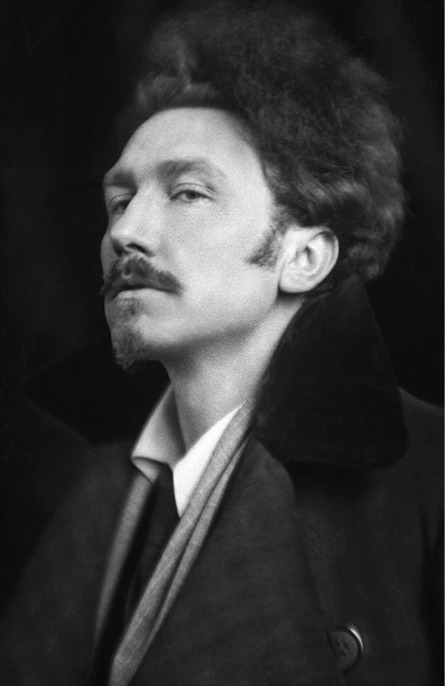

Ezra Pound pulled Joyce from obscurity and arranged for

The Little Review

to serialize

Ulysses.

When legal troubles loomed for the magazine, he insisted on printing Joyce’s novel “even if we go bust and die in a blaze of suppression.”

Margaret Anderson, the founder and editor of

The Little Review,

which serialized much of

Ulysses

from 1918 to 1921.

Dora Marsden, founder and editor of

The Egoist,

arrested for suffrage activism in London, 1909.

T. S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf in 1924. Woolf declined to print the first chapters of

Ulysses

in 1918, though she changed her mind about Joyce’s novel after Eliot insisted that she read it in its entirety. “It is,” Eliot claimed, “a book to which we are all indebted and from which none of us can escape.”

Other books

Shaka II by Mike Resnick

Picking up the Pieces by Prince, Jessica

Sometimes We Ran (Book 3): Rescue by Drivick, Stephen

Sexiest Vampire Alive by Sparks, Kerrelyn

Remember Our Song by Emma South

The Reckoning - 3 by Sharon Kay Penman

Burn for Me by Shiloh Walker

The Child Bride by Cathy Glass

A Well-tempered Heart by Jan-Philipp Sendker