The Missing Dog Is Spotted (12 page)

Read The Missing Dog Is Spotted Online

Authors: Jessica Scott Kerrin

“What I really want to do is to get everyone I like in the same place and then have no one leave. That would be great.”

Trevor paused as the audience mulled this over.

“But it wouldn't work. Someone would leave. Someone always leaves. Usually, it's me. Then I have to say goodbye.”

Some of the students closest to him nodded sadly.

“My parents are pilots,” Trevor continued. “They fly around the world, and they often tell me about having a perfect view of the curve of earth in the cockpit. They also tell me this â whenever you leave a place, if you keep going, eventually you will return to the exact spot you started. You never truly leave. So even though we can't stay together, this time capsule will hold a part of each and every one of us in the same place, a special place that we will never truly leave. See you in fifty years.”

There was a heavy silence. Some students wiped at their eyes, and then the audience broke into wild applause. Mr. Easton gave Trevor a hug.

After the crowd settled, Mr. Easton asked Trevor to unlock his locker. Trevor spun the combination.

Twenty-eight. Thirty-four. Eighteen.

He opened the door and removed his knapsack for the last time. The locker was now empty.

“Do you want to put anything of your own in the time capsule before the others add their last assignment?” Mr. Easton asked.

Even after weeks had gone by, giving Trevor plenty of time to think about what he could put into his locker, he still had drawn a complete blank. His knapsack was heavy at his feet. He looked down at it. It was then that he realized with deep regret that he wasn't going to give his gift to Loyola after all. As brave as he had been to give his speech, he knew he wasn't brave enough to let Loyola know how he really felt about her. Besides, she didn't think of him as a true friend, not really. They had shared some good times with the dogs. That was it. She, like all others, would forget about him and his magnificent speech, even before the summer was over.

So he reached into his knapsack, took out her book and slid it onto the top shelf of the locker.

“That's it?” Mr. Easton asked.

“That's it,” Trevor said in a little voice.

And then he placed his last assignment, sealed in an envelope with Mr. Easton's name written on it in his best penmanship, on the bottom of the locker.

One by one, the others in grade six came forward and did the same, each story sealed in an envelope addressed to Mr. Easton. Loyola, who stood at the back of the crowd, was last. Only she didn't place her envelope on the top of the pile. She lifted the pile up and placed hers on the bottom as Trevor watched, confused.

She stood and turned to face the crowd. Everyone gathered had a clear view of her on the platform.

“Because we have so much in common â our love of dogs and solving puzzles and cheese sandwiches â I placed my envelope next to Trevor's,” she announced in the loudest voice he had ever heard her speak. It rang out beautifully to match her infectious laughter.

Just like that, Loyola had taken the first bold step to declare their friendship in front of the entire school. And no one had a word to say about it as she proudly made her way to the back of the crowd.

“Now the plaque,” the principal declared.

Trevor shut the door to the locker and spun the dial on the lock. He pulled on the hasp. Locked. Mr. Easton stuck the plaque to the door. On it was Trevor's name, the year of their graduation and the year that the time capsule was to be reopened.

There was more applause along with hoots and cheers. Then the band fired up. They played an old-time song called “Hello, Goodbye!” and the choir sang along in rounds. During the final chorus, everyone in the audience clapped and stomped to the beat.

And then that was it. The ceremony was over. The crowd started to break up and drift back to their classrooms for final dismissal.

“Well done,” Mr. Easton said, putting his arm around Trevor and steering him back to class.

Trevor should have felt great after the speech he had given, but he felt worse than worse. He should have given his gift to Loyola after all. Now it was locked away in the time capsule, practically forever. Any minute, the final bell would ring! And she'd be gone!

He slid behind his desk feeling numb. He barely heard the whoops and cheers when the bell rang moments later. He drifted with the crowd of merrymakers down the stairs and out the front door of the school. He barely took in who was saying goodbye to him as they swept past.

“Peace,” Bertram said.

“Farewell,” Noah said.

“Later,” Miller said.

And Craig just fondly waved, too stuffed up for words.

Trevor plunked down on the steps, trying to pull his thoughts together as the school cleared out of teachers and students alike.

The crowd thinned.

Then there was just a trickle coming out the door.

Trevor was alone.

Not quite.

Someone sat down beside him, a giant bag filled with the contents of her locker slung over her shoulder.

Loyola.

“What did you write about in your last assignment?” she asked in her bold new voice that said, “I'm tall. So what?”

“We're not supposed to tell, are we?” he asked, his confused thoughts running every which way.

“I'll tell you if you tell me,” Loyola said in her new-found voice.

“Buster,” Trevor admitted.

“Me, too!” she exclaimed. “And like Mr. Easton said, I do feel better now that I've written it all down. I think things will work out for everyone.”

“Me, too,” he echoed, starting to realize that it was true.

“Which way are you going?” she asked.

“That way,” Trevor pointed in the direction of his home, which was not his home anymore, not after today.

“Me, too,” she said. “Want to walk together?”

Walk together?

thought Trevor.

Without dogs or other

distractions?

He slowly nodded.

“Time to fly,” she said. She got up with her bag.

Trevor stood, too. He was thrilled. Thrilled to be walking with Loyola.

No dogs. Just him.

They chatted as they strolled along the sidewalk. Mostly they talked about the funny things that Duncan had done, or Scout or MacPherson. When they got past the yawning iron gate of the Twillingate Cemetery, Loyola stopped short.

“I go this way now,” she said, pointing to a street that intersected the one that they were on, the one that would lead her home. “I know you like hellos more than goodbyes,” she added, her voice trailing away.

Trevor cut her off. He stood tall, stepped forward and gave her a really big hug.

She hugged back, then turned to go.

“Wait,” Trevor said.

She paused.

He reached into his knapsack and pulled out his notepad and a pen. He tore off a sheet of paper and wrote down three numbers.

Twenty-eight. Thirty-four. Eighteen.

He handed her the paper.

“What's this?” she asked.

Trevor knew she'd figure out that it was the combination lock to his time capsule. He knew she'd make her way back to the school over the summer and open the locker. She'd find the book of codes he had left on the top shelf, and she'd know it was for her because she'd remember that she had told him about how much she liked solving puzzles.

Friends knew these things about each other.

“It's a mystery,” Trevor said, and he grinned. “It's something I'm leaving for you to figure out. From one Queensview Mystery Book Club member to another.”

Loyola nodded slowly, but she wore a beautiful smile.

And so they parted as friends without having to say goodbye at all.

Afterword

WHEN WE

lived in the countryside near Peggy's Cove, Nova Scotia, we owned a dog named Astro. She was a nutty English springer spaniel who was full of beans and who would get lost in the woods from time to time when we took her out with friends on long hikes. We'd call and call until our voices were hoarse and night would fall, and we'd have to come home alone with our burned-out flashlights.

The worrying was relentless. What if she was hungry? What if she hurt herself? What if she came up against a bear?

Yet Astro would always find her way home by the morning, delighted by her midnight adventure but a little bit sheepish and grateful for her cozy bed.

Astro lived to be a happy old dog. Even after all these years, we still have her portrait on our family-room wall and her leash in our front porch.

Dogs, and other pets we love dearly, sometimes have to leave us. But they never truly leave. And if you ever need proof, just ask someone you know about a dog that they used to own. They'll tell you a story or two about cherished moments, and then suddenly during the telling of the story, they'll catch a fleeting glimpse â their missing dog now spotted â however briefly, but forever safe in their hearts.

Thank you to Sheila Barry and the exceptional staff at Groundwood for supporting my efforts to extend

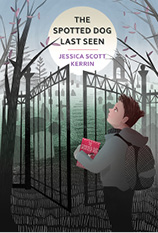

The Spotted Dog Last Seen

into this prequel. Thank you also to Katie, Pepper, Jody, Maggie, Myles, Lark, Tiger, Dudley, Balto and Dougall, all good dogs, and to their owners who loved them.

Also available

The Spotted Dog Last Seen

Read on for a preview

Prologue

THIS IS A LARGE

cemetery for such a small town. And old. You told us once that some of the gravestones date back hundreds of years. But I didn't make a habit of hanging out in cemeteries when you were doing the telling. Believe me, I'd rather have been anywhere else.

Did you know I arrived alone that first day? Pascal Bender and Merrilee Takahashi were supposed to meet me at one o'clock by the iron gate. There I stood. It was three minutes past one. And then it started to rain.

The first raindrops plopped against the grave markers, which teetered this way and that over the lumpy ground. I was sure that even a ghost could knock down some of them, just by floating past at sunset.

Sorry. I know how you felt about ghosts.

And vampires. And zombies.

I could see that there were different types of stones â brown, white, bluish gray â but I didn't know which was which.

And all those carved symbols on the stones? Well, the angels were easy to spot. Their wings were a dead giveaway. But I didn't know what the other symbols meant, like the ones with clasping hands or a baby lamb. And all those skulls and crossbones? I was sure that meant the cemetery was full of dead pirates!

When Pascal and Merrilee didn't show up, I thought I must be waiting in the wrong section. I was standing in the oldest part of the cemetery, where the stones were covered in lichen and eroded words. Maybe we were supposed to start in the newer section and work our way backwards through time.

But I didn't know where the newer part of the cemetery might be. I certainly didn't know who would be buried there.

You.

One

â

Reading

Weathered Marble

WIND HOWLED

through the trees that surrounded me. Boughs overhead moaned. The roots beneath my feet wrapped tightly around the buried coffins to hold the trees to the ground.

And all the while, I stood at the cemetery gate trying my best to ignore the posted warning signs:

Beware of Falling Gravestones

Enter at Your Own Risk

Closed at Sunset

No Dogs Allowed

Just who did the gate think it was fooling? Sure, it looked secure enough, but when it was locked at night, the gate would be useless at keeping anything inside that wanted to get out.

And I wasn't worried about the living.

Then I heard a shrill four-fingered whistle across the street from the cemetery.

“Derek!” the whistler hollered from the front steps of the old stone library that had once been a church. “We're in here!”

I grabbed my knapsack and bolted from the cemetery gate, cold heebie-jeebies charging down my spine. But when I got to the crosswalk, I stopped in my tracks.

I looked left, right, left, and then left, right, left again before taking a careful step off the curb. The extra checking was a safety habit that I couldn't seem to shake, not even when fleeing a spooky graveyard in the cold rain. After crossing the street, I scrambled up the granite steps to the library with relief.

I'd never been to this library before. Even though it was no longer a church, its stained-glass windows had been saved. Each one was filled with scenes of people in robes and sandals â the men with beards, the women's heads covered by hoods, many of them weeping or looking up to the sky with their hands clasped, some on their knees, heads bowed, beams of light shining down.

“You must be Derek. I'm Loyola Louden.”

Loyola was basketball-player tall compared to my own husky self. If you asked me what my favorite subject at school was, I would not say, “Gym.” But I was guessing that Loyola sure would. She effortlessly held a large stack of books with one hand as she shook my hand with her other gigantic one. At least she didn't squeeze hard. I really hated that.

“Do you supervise cemetery duty?” I asked.

“No. I'm a university student,” Loyola said. “I work here part-time.”

“I'm supposed to report for cemetery duty by the gate,” I explained.

“The Twillingate Cemetery Brigade gives lessons here whenever it's raining.”

“Lessons?”

I repeated with alarm. I thought cemetery duty was supposed to be dead easy, like picking up litter or planting flowers around that ugly towering gate or straightening gravestones that looked like they were about to topple over.

She ignored my unease and led me inside, past stacks and stacks of books, to the research area where Pascal and Merrilee sat waiting.

“Hey,” I said to them without much enthusiasm.

Merrilee answered by pushing her glasses higher on her nose. Pascal gave me a tight nod. They looked about as glum as I felt about our new school assignment.

Queensview Elementary has been getting grade-six students to do community service work during the last three months of the school year for as long as anyone can remember. Usually, everyone gets to pick from a list of places that need volunteers. Soup kitchens. Homeless shelters. Seniors' residences. That kind of thing.

I thought the seniors would be okay. I'd sit around playing cards with them and whatnot. Talk about whatever war was going on. How hard could that be?

But I was sick at home the day we made our selections. Not really sick, I just had an eye infection. Pink eye is what they call it. Supposed to be highly spreadable. By the time I got back to school, all that was left was cemetery duty.

“Do you want me to call your teacher?” my mom had blurted as soon she found out. “See if someone will switch with you?”

“No one's dying to go to the cemetery,” I had said, which is pretty funny, now that I think about it. “And anyway, I'll be fine.”

She had turned away, but not before I saw her frown.

“I'll be fine,” I had repeated, trying to convince myself more than her.

I slid into the empty seat beside Pascal. I was not used to seeing him out of school uniform, or Merrilee for that matter, although I spotted her familiar red plastic jacket with the bunnies-and-carrots print draped over her chair. I hoped they would notice my t-shirt. It read,

Change is good. You go first

.

I like to collect sayings I've heard and print the best ones on t-shirts. Lately, I had been giving them away as gifts. My dad got,

I'm fine

, with a bloodstain printed beneath the words. He likes to wear it in his workshop in the garage or when he goes to the hardware store.

I thought that if I were to make a t-shirt for Pascal, it might read,

There are three kinds of people: those who are good at math and those who aren't

. Pascal had an answer for everything, even if he had to take a wild stab in the dark.

But I wasn't so sure about Merrilee. I didn't know her as well as Pascal, although I remembered that she was quite the archaeologist when she was little. She had a peculiar habit of burying things in the school's sandbox, then later digging them up. Maybe her t-shirt would read,

X marks the spot

.

The cemetery work crew we were assigned to arrived in full force â all three of them.

“Students, I'd like you to meet the Twillingate Cemetery Brigade. This is Mr. Creelman, Mr. Preeble and Mr. Wooster,” Loyola announced.

Each one glowered more fiercely than the next. All three stood dripping in their raincoats. Loyola eyed the stack of books that Merrilee had been leafing through and quietly moved them to another table for protection.

Creelman broke away from the trio. His thick white eyebrows reminded me of a portrait of my grandfather that I'd done back in grade one. I had been really inventive by gluing on cotton balls for his eyebrows.

“No sense cleaning grave markers today,” he announced, digging out a thick wad of wrinkled yellowed notes from inside his raincoat pocket. “Instead, you'll have your first lesson on how to read weathered stones.”

Creelman paused. Was he expecting us to clap? All he got was the sound of rain slamming against the cheerless stained glass above our heads.

“Let's see how much you know,” Creelman said, plowing along even without applause. “What are most of our nineteenth-century stones made out of?”

“Nineteenth century,” Pascal repeated. “You mean the really old ones?”

“Not old! Weathered!” Creelman barked, pounding the table for effect.

I startled. Merrilee flinched.

“Concrete?” Pascal guessed undaunted.

As I said, he had an answer for everything, but even I knew that he was way, way off.

Creelman stared him down, probably trying to figure out if Pascal was joking or not. His cotton-ball eyebrows collided into one straight line.

“Anybody else?” he growled, turning to Merrilee and me.

We quickly shook our heads, me unable to look away from those comical brows.

“Marble,” he pronounced. And then he repeated himself as if we were idiots. “Mar-ble.”

We shifted in our hard wooden seats.

“Does marble last forever?” he asked, eyebrows now arched.

It felt like a trick question. Merrilee and I didn't bite, but Pascal quickly weighed in.

“Yes, it does. For sure. Look at the ancient Greek statues.”

Creelman snorted.

“Ancient Greek statues aren't forever!” he declared, pounding the table again. “That's why there aren't many left and they end up inside museums for protection!”

He had a point. It even silenced Pascal for a moment.

“And do you know why marble doesn't last?” Creelman continued, laying another trap.

I looked around for help. Preeble and Wooster were standing off to the side appearing smug, as if they knew the answers but weren't about to share. Loyola was gone. I spotted her back at the front desk helping a daycare group sign out picture books.

“Sulfur dioxide,” Creelman declared, but he didn't pound the table. Instead, he stood with his arms crossed, giving us plenty of time for this fact to sink in.

I wondered if my mom should make the call about cemetery duty after all.

“And where does sulfur dioxide come from?” Creelman demanded.

He was relentless!

Desperately, I looked over to Loyola, who had finished checking out the books. I caught her eye, but then she quickly busied herself by sharpening pencils. She was not coming back any time soon. Traitor!

“The periodic table?” Pascal guessed.

The periodic table?

I was tempted to inch my chair closer to Merrilee so that Pascal had plenty of room to dig his own grave. Good grief!

“Burning coal power!” Creelman replied, his eyes widening.

Even though we knew it was coming, all three of us jumped when he pounded the table yet again.

“Sulfur dioxide is the enemy of gravestones,” Creelman continued, as if he were talking about some new plague or a campfire ghost story. “It steals letters and makes our grave markers unreadable.”

Pollution. Got it. I sneaked a peek at the wall clock. This was going to be a very long afternoon. I almost wished I was back in the cemetery, despite the rain.

Almost.

“Part of your job will be to read and record our gravestones so that the information doesn't disappear,” he leaned in, “

forever

.”

As if rehearsed, Preeble pulled a small mirror from the pocket of his raincoat, handed it to Creelman, then took a precise step back beside Wooster. Creelman moved beneath the nearest stained-glass window and held the mirror in front of the engraved plaque mounted in the shadow of the windowsill.

“If there's plenty of light, like in this library, you can use a mirror. You hold it over the gravestone like this,” explained Creelman, flashing the mirror across the plaque, “and redirect the light at an angle so that the carved words are highlighted in shadows. See?”

The words etched on the plaque really popped out. It read,

Restored by the Twillingate Cemetery Brigade

.

Despite the table pounding, I was a little impressed.

“But sometimes there's not much light,” Creelman said, his eyebrows casting a shadow, his face clouding over.

That was Wooster's cue to pull out a paintbrush from his pocket and hand it to Creelman, then return to his spot beside Preeble.

“What you do is take a brush and some plain water.” Creelman demonstrated by brushing the air. “When you wet the surface, you move the dirt into the carved letters and lighten the surrounding surface at the same time. Then it's easier to read.”

Makes sense, I thought. It was simple to follow now that the table pounding had stopped.

Creelman began to lay out his yellowed sheets of paper in front of us.

“Even with all that, you'll still need to become an expert at deciphering engraved characters that have partially disappeared. Have a look.”

The three of us leaned in. Creelman's papers contained charts of what carved numbers looked like after they had weathered for one hundred years and then two hundred years.

“I need someone to demonstrate,” Creelman said. He slowly scanned the three of us, and his eyes landed on me.

“Okay,” I croaked, having very little choice.

He handed me a nubby pencil.

“Write the numbers 1 through 9 on this piece of paper,” he instructed.

I did.

“Now look. See how all your strokes are even?”

Everyone inspected my numbers. I have to admit that I do write neatly. My notebook where I record my collection of t-shirt sayings is a thing of beauty.

“But it isn't so with numbers hand-carved in marble. They are carved by uneven chisel strokes. Take the number 4. The carver has to lean in hard to make one long downward stroke, and then finish the rest of the number with short light taps. Over time, those little strokes fade away, leaving only the deep downward stroke, until finally you can't tell a 1 from a 4.”

“How do we figure out which is which?” Pascal asked.

“Good question!” Creelman replied, not scowling for the first time that afternoon. “Your only clue is the spacing. Look here. The downward strokes in the year 1811 are spaced more evenly than the year 1814.”

Even Merrilee nodded in interest.

“The numbers 2, 3 and 5 are in the next group. Over time, only the deep curve on the right side of all three numbers remains â here at the top of the 2, here at the bottom of the 5 and here, twice for the number 3.”

By now, I'd completely forgotten about the cemetery. As we studied Creelman's charts, I began to feel as if we were training to become detectives for hidden codes.

“Next are the numbers 6, 9 and 0. They also have deep curves on both sides that remain over time. The number 6 will have a long curve on the left and a short curve on the right. Nine is just the opposite. And see here? Zero will have two long curves.”

Look at that, I thought, taking in the lesson.

“Last are the numbers 7 and 8. When carvers engrave an 8, they have to cut a deep diagonal line in the middle that is the last to fade away. But unlike the number 8, the number 7 has a long deep diagonal cut that runs all the way to the bottom.”

Then, just when I was not expecting it, Creelman pounded the table and declared, “Sevens never die!”

From the safety of her desk, Loyola Louden looked our way with a startle.

The lights flickered overhead.

“Now, we're going to leave you to study these charts. When we get back, there'll be a quiz. We can't have you making any errors when you're recording our gravestones.”

With that, Creelman, Preeble and Wooster marched past the book stacks and out the front door, leaving behind the yellowed sheets, a mirror and three puddles on the marble floor.