The Midwife Trilogy (45 page)

Read The Midwife Trilogy Online

Authors: Jennifer Worth

Tags: #General, #Health & Fitness, #Pregnancy & Childbirth, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Medical, #Gynecology & Obstetrics

This rapid succession of vowels would be unintelligible in speech without the use of the glottal stop.

‘t’ can come in for other changes. Sometimes it becomes a ‘d’, e.g.

bidda budder

(bit of butter),

arkadim

(hark at him),

all ober da place

(all over the place).

‘t’ followed by ‘r’ becomes ‘ch’, e.g.

chrees

(trees),

chrains

(trains).

‘t’ followed by another word beginning with a vowel again becomes ‘ch’, e.g.

whachouadoin’ov?

(what are you doing?),

doncha loike i:?

(don’t you like it?).

Sometimes ‘t’ is heavily emphasised, becoming ‘ter’, e.g.

gichaw coa-ter, we’re goin’ah-ter

(get your coat, we’re going out).

‘th’ is nearly always replaced by ‘f’ or ‘v,’ e.g.

vis

,

va

’,

vese

and

vose

(this, that, these and those); and

fink

,

fings

,

fanks

,

frough

(think, things, thanks, through).

‘f’ and ‘v’ were so common in the 1950s and the sound was so impressed into my aural memory that I have found it very difficult to write the Cockney speech without using them.

Ve baby

,

ve midwife

, and so on, came more naturally than Standard English. The widespread use of ‘f’ and ‘v’ may have arisen early in the twentieth century because practically all men, and not a few women, usually had a limp, wet Woodbine hanging off the lower lip. The articulation of an ‘f’ or ‘v’ would leave the soggy appendage undisturbed, but the fricative ‘th’ might result in it being spat out!

Over decades speech changes, and I believe that the ‘f’ and ‘v’ are dying out. Perhaps this is because cigarettes are filter tipped and thrown away! The succulent remains of a Woodbine are not preserved and cherished and rolled around the lips as they used to be.

On the subject of change, the Dickensian reversal of ‘v’ and ‘w’ seems to have dropped out of Cockney speech altogether, e.g.

vater

(water) and

wery

(very). Occasionally an old-fashioned shopkeeper (are there any left?) can be heard to say

welly good, sir

, but not welly often!

As speed is all important, ‘h’ is seldom used. However, the suggestion (which is a sort of tasteless joke) that Cockneys trying to ‘talk proper’ put ‘h’ in the wrong places is not quite correct. I have listened very carefully, and only noticed an aspirated ‘h’ used for special emphasis, often with a glottal stop thrown in as well, e.g.

oie was :henraged

(I was enraged);

bleedin’ ca:s :heverywhere

(bleeding cats everywhere).

‘L’ in the middle or end of a word is usually lost and replaced by ‘oo’ or ‘w’. This is just about impossible to write convincingly. Consider:

li:oo

(little);

bo:oo

(bottle);

vere’s a sayoo of too-oos darn Mioowaoo

(there is a sale of tools down Millwall).

‘N’ and ‘m’ seem to be virtually interchangeable; a patient of mine had an

emforced rest due to an emflamed leg

. Another found

aoo vose en:y bo:oos ah:side ve ’ahse enbarrussin

’. (all those empty bottles outside the house embarrassing). In Poplar people used to

eat bre:m bu:er

(bread and butter).

There are many other consonant changes, which vary from family to family and from street to street. ‘Sh’, ‘ch’, ‘zh’ (as in treasure) and ‘j’ replace almost anything, e.g.

we’re garn :a shea-shoide

(we’re going to the seaside).

Ve doctor, ’e shpozhezh, vish fing wazh a washp shting azh wha: ‘azh shwelled up loike

(the doctor he supposes, this thing was a wasp sting that has swelled up).

Wocha

is the most common of all Cockney greetings, which has passed into Standard English. It is a very old form of “What are you (doing)?” The ‘ch’ in

wocha

replaces two or three words.

‘J’ can replace ‘d’.

Jury Lane’s a jraugh:y ole plashe

. (Drury Lane’s a draughty old place.)

‘J’ and ‘zh’ frequently join words together, e.g.

Izee comin’, djou fink?

(Is he coming, do you think?) ’

Azhye mum?

(How is your Mum?).

The softening of fricatives may have arisen from the fag-end already mentioned. In fact to speak the dialect, one only has to purse the lips, imagine a Woodbine stuck somewhere on the lower lip, and let the words roll out with the minimum of mouth movement, and you’ve got it!

If you think representing consonants in written Cockney speech is hard, that is only because you haven’t tried the vowels! There are five vowels in the alphabet, plus ‘y’ and ‘w’, and no possible combination of these seven sounds can convey the complexity of Cockney vowels, which are washed and soaped and rinsed and put through the wringer, then stretched and twisted beyond anything that any phonetician can imagine. Italian is the language of pure vowels (the singer’s delight). English has diphthongs and a few triphthongs. Cockney has quadraphthongs and quinquaphthongs, septaphthongs and octophthongs, and God knows how many more. They all differ from person to person, from time to time, from place to place, and from meaning to meaning. Vowels are the vehicle by which voice inflexion is carried, and singers spend years studying the tone, colour and meaning that can be placed on vowels. The Cockney does it from birth.

Many Cockney vowels are elongated and made unnecessarily complex, e.g.

loiedy

,

lahoiedy

(lady). Others are reduced to almost nothing, e.g.

fawna

(foreigner).

Diphthongs in Standard English can become a single pure vowel in Cockney, e.g.

par

(power),

sar

(sour).

In writing, to render ‘I’ as ‘oi’ gives the wrong impression, because Cockneys do not say ‘oi’, as in oil or joy. They say something like

aoiee

.

‘Ow’ becomes an approximation of ‘aehr’, e.g.

aehr naehr braehn caehr

(how now brown cow).

‘O’ (as in go) is ‘eao’ (or something like it), e.g. ‘

e breaok ’is leig, feoo off of a waoo, ’e did

(he broke his leg, fell off of the wall, he did); ’

e niver aw: :oo ’ave bin up vere, aoiee teoozh’im

(he never ought to have been up there, I tells him).

I was struggling to express the Cockney accent in written form, until a professor of English Literature said to me, “You will not succeed, because it cannot be done. People have been trying since the fifteenth century, but it has never been successful.”

What a relief! I will struggle no more.

Grammar, Syntax and Idiom

In all countries at all times in history, the poorest of the poor have tended to live around the docks. Trapped by poverty, they have become isolated, and remained more or less static. This may be why Poplar of the 1950s existed in a sort of time warp, with habits, customs and family life being somewhat behind the times. With the closure of the docks, this changed.

Speech is a living entity, changing with the people. But Cockney language changes have lagged far behind those of middle-class English. Many Cockney speech forms - idioms, grammar and syntax - which today are considered flawed, are, in fact, very ancient speech forms that can be traced back to Tudor times.

Here are some typical examples:

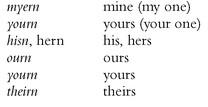

Possessive (conjugated)

The ‘-self’ form becomes:

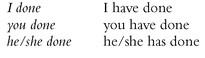

Verbs frequently take the third person singular for the whole conjugation:

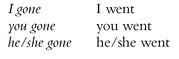

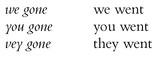

Some expressions in the past tense use the past participle on its own, without the auxiliary (have, did):