The Memoirs of Catherine the Great (42 page)

170

August 14, 1758 (n.s.).

171

May 30, 1758.

172

; May 23, 1758.

173

June 25/July 6, 1758.

174

Horace,

Ars Poetica,

1. 139.

175

In his memoirs (1: 327–31), Poniatowski describes how the Grand Duke and his drunken party met him as he arrived at Oranienbaum to see Catherine. After snide comments by his mistress, the Grand Duke had him detained as he was leaving. The Grand Duke “first asked me in clear terms whether I had . . . his wife. I told him no.” The Grand Duke brought in Alexander Shuvalov as head of the Secret Chancery, to whom Poniatowski said, “I believe that you understand, Monsieur, that it is absolutely crucial for the honor of your own court that all of this end with as little fuss as possible and you get me out of here as soon as possible.” Shuvalov agreed, and gave Poniatowski a carriage to leave. Two days later he received a note from Catherine, indicating “that she had taken several steps to win over her husband’s mistress.” Catherine told him to meet her at Peterhof, where she would be with the court for St. Peter’s Day, June 29/July 11, 1758. That evening Catherine finds Poniatowski in the Grand Duke’s chamber. ‡ This passage appears in final memoirs before what should be the end of 1757 (before the birth of her daughter), but which Catherine mistakenly thinks is 1758. Here it comes after the middle of 1758, or what Catherine thinks is 1759.

APPENDICES

CATHERINE’S OUTLINE, 1756–59

Return to town. The chevalier W[illiams] departs. Count P[oniatowski] returns as the minister from Pol[and] toward the

end of 1756.

The assignations continue on the same footing. The intrigues of Brockdorff and the Holstein entourage, a number of officers from this country in the Grand Duke’s chambers. What he thinks of Russia, his lies; the Elendsheim affair, my opposition to his arrest; he is arrested just as Holmer had been, without evidence, with neither an accuser nor an accusation; my views on this subject.

Beginning in 1757.

Continuation of the Grand Duke’s affairs with Madame Teplova, with Countess Vorontsova, with the Princess of Courland, the danger she risked; Marshal Razumovsky’s affair with Madame Naryshkina; Lev N[aryshkin’s] promise, how they wanted to marry him off and how he . . . How we went one day . . . to Marshal Razumovsky’s home one day during Lent, and how . . . Departure for the country, Pechlin’s death, Stambke’s arrival. In the month of July news of the capture of Memel by the treaty of June 24th. In the month of August, news of the battle of Gros Jägerndorf, which had occurred on the 19th of the same month. I held a party in my garden on the day of the Te Deum, which consisted of a large dinner, and a roast ox for my garden workers and for the masons, who were building a man-made mountain. In the autumn, conversation with the Emp[ress] at the Summer Palace. Retreat of Marshal Apraksin, which has the appearance of flight. Why. Sinister explanation. His difficulties, my letters at the request of the Grand Chancellor. The Marshal does not answer.

Winter of 1757. Beginning of 1758,

the dispatch of Fermor, capture of Königsberg on January 18th. Marshal Apraksin is taken to Triruki. His trial, his death. General Lieven, mixed up in this affair. His devotion to me, what he says about this to Count Pon[iatowski] at Count Esterhazy’s masked ball. Arrival of Prince Charles of Saxony. New pregnancy. How he was received, the Grand Duke barely honors him, hardly talks to him; the Princess of Courland’s part in this. Prince Charles joins the army. Departure for Oranienbaum, the party that I give there for . . . the effect of this party.

163

His Imperial Highness reattaches himself to Countess Vorontsova, he increasingly shuns me; the party I give at Oranienbaum, the effect of this party. How Lev turns his back on me in the spring of this year, how he attaches himself to the Grand Duke, how his sister-in-law and I whipped him. The Empress’s suffering over the Battle of Zorndorf; it is declared won; the truth was that both sides were beaten, the Te Deum is not sung until the third day, our troops however sang it on the battlefield. The Emp[ress] on the Battle of Zorndorf.

Count Schwerin, the adjutant general of the

King of Prussia is taken prisoner. Fermor gives Lieutenant Captain Grigory Orlov the

order to take this prisoner of war to Petersburg.

164

The Empress goes from Peterhof to Tsarskoe Selo; what happens to her on September 8th, the day of the Virgin’s Nativity, how I learn about it.

165

Return to town. I do not appear in public, believing that I am close to giving birth; I am off by a month; what Lev N[aryshkin] comes to tell me about my pregnancy in October. Why I had my big bed removed and thereafter only slept in my little bed and this in another room. October, news of the recall of Count P[oniatowski]. Count Bestuzhev’s anger about this, my delivery in December,

166

;

celebrations of this, fireworks on January 1st, 1759. How Peter Shuvalov brings me the plan for the fireworks, where I hide my company and how I receive him. During carnival three weddings at court, disastrous weddings of L[ev] N[aryshkin], of Strogonov, and of B[uturlin];

167

bets about these, who of the three would first be cuckolded. Arrest of Count Bestuzhev,

168

of my jeweler Bernardi, of Elagin, Adadurov; Shkurin’s secret contacts, which fail. The Grand Duke no longer comes into my chambers. Discovery of Stambke’s and Count Pon[iatowski’s] secret contacts with Count Bestuzhev, dismissal of Stambke; the affairs of Holstein are taken from me, someone named Wolff is brought in, they are given to him. The Grand Duke is made to fear speaking to me during the Bestuzhev affair. How I wanted to go to the Comédie Russe and how they wanted to keep me from going there, how I wanted to write to the Emp[ress] about why they wanted to keep me from going. I am warned that there is talk of dismissing me, my decision concerning this. I demand to be dismissed. I write of this to the Empress, what this letter contained; I say that I am sick and no longer go out. I am alone in my chambers, I read five volumes of the

Histoire des voyages

with the map on the table and the

Encyclopédie

for my amusement. The Empress has me informed that she wants to speak to me. The Grand Duke learned of this, he became jealous of it and demands to be present at this conversation. How this conversation took place.

169

The Empress’s conduct, her words, her actions, the Grand Duke’s conduct on this occasion, mine, how I began upon entering.

What the Empress said to me while approaching her toiletry table, what I replied to her. She dismisses us, what Alexander Shuvalov comes to tell me on her behalf. How I reply. How she sends Count Vorontsov to me a short time later. The Prince of Saxony returns to Petersburg after the Battle of Zorndorf,

170

how he had fled to Landsberg; because of his cowardice, the Grand Duke does not speak to him, nor does he wish to have anything to do with him. There is talk of making Prince Charles Duke of Courland, the Princess of Courland makes the Grand Duke angry at Prince Charles; third engagement of the Princess of Courland with Cherkasov.

How the Grand Duke wanted to go to Holstein, what he did to this end, what was

done, how I was told about it; what I said, what Count Vorontsov told me about it, this should

be put at the end of 1759. Departure for the country;

171

before this second conversation with the Emp[ress] in private, the Empress’s decision about my situation.

172

;

This was the day following Prince Charles’s visit to our residence, what Count P[oniatowski] said to me rather loudly

upon departing was heard, I think, by Brockdor f, who was quite near us. I take the waters,

where I stay. How Count P[oniatowski] is arrested leaving my residence.

173

Brockdor f speaks

of killing him. Lev N[aryshkin] advises giving him to Count Ale[xander] Sh[uvalov], who

hands him to his son-in-law and leaves for Peterhof. Ivan Sh[uvalov] advises him to have

him released, which he does. Ale[xander] Sh[uvalov] comes the following day to tell me what

happened overnight, I knew nothing of it, the Grand Duke comes to my chambers, speaks to me,

they had appeased him because they did not want any rupture, he proposes that I see, demands

that I see Countess Eliz[abeth] V[orontsova].

She comes to my chambers, I remain in bed all

day, quite overcome. The evening of the following day, I receive from Alex[ander] Sh[uvalov]

a note from the Empress, written in the hand of Ivan Sh[uvalov] and signed Eli[zabeth], in

which she begs me not to be distressed and to come to Peterhof for the feast of St. Peter as if

nothing had happened. I reply to this and show her my heartfelt gratitude. I go to Peterhof.

During the St. Peter’s day ball, Count Rzewuski says to me: my friend asked me to tell you that

by the channel of La Grelée and that of Count Branicki, everything is arranged and that this

evening he hopes to have the pleasure of seeing you in the Grand Duke’s chambers. Now, he had

never been there. I replied to Count Rzewuski: tell your friend that I find this conclusion

completely ridiculous and that [a mountain has given birth to a mouse].

174

Back from [supper]

I went to bed without hearing discussion of anything. Between two and three in the morning

I heard the curtain of my bed being drawn and I awoke with a start; it was the Grand Duke,

who told me to get up and follow him; whom I find in his chambers.

175

There we all are, the best friends in the world. How until Count P[oniatowski’s] departure, the Grand Duke spent two

and three evenings per week in my circle and drank my English beer; so that as a result of this

episode and that of the following winter there was no trust to be had in His Imperial High

ness in anything, and things took such a turn that it was necessary to perish with him, by him, or else to try to save oneself from the wreckage and to save my children, and the state.

‡

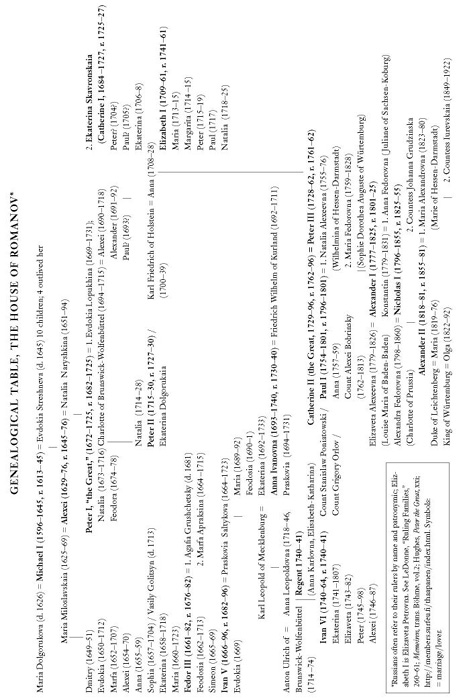

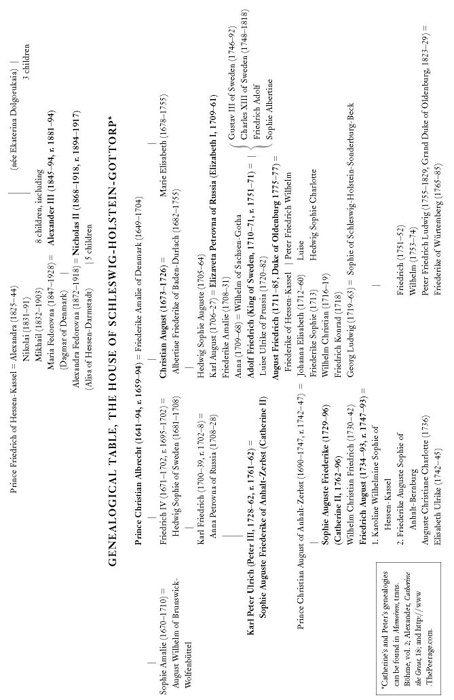

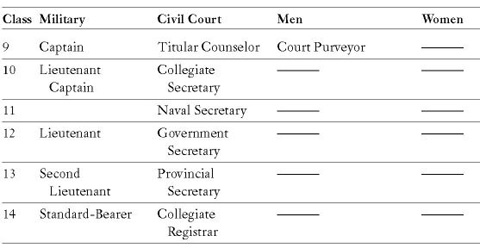

TABLE OF RANKS AND CHIVALRIC ORDERS

In the eighteenth century, Russian noble status depended on the combination of family, noble title, service rank, profession, wealth, and education. The importance of these factors that accorded prestige was for the most part unspoken, yet essential for understanding individuals and their relationships. This brief note explains the nature of noble rank, a phenomenon that is central to the personal and political maneuvering described in Catherine’s memoirs. Although Catherine’s familiar tone gives the impression that she is quite like us, at the same time, the terms in which she thought of herself and others were utterly different.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Russian nobility comprised a mere 1.5 percent of the population, ranging from titled landowners to impoverished, landless civil servants, and distinguished as an estate by legal privileges.

1

In 1722, in his drive to modernize Russia, Peter the Great instituted the Table of Ranks to create a sufficient and able bureaucracy and army. He forced the nobility to serve the state in order to acquire service rank (

chin

), which became the determining factor of social identity. He also allowed non-nobles to attain noble ranks through their service. The importance of service rank is apparent in the fact that a nobleman without it was technically a minor, though still a noble. After 1762, even though nobles no longer had to serve, most did in order to gain rank.

There were fourteen ranks in the military, civil service, and the court, which remained in effect from 1722 until 1917. Fourteen was the lowest rank and one was the highest. Given equal ranks, military rank was superior to court rank, which in turn was superior to the civil service, and the jobs assigned to ranks changed greatly over time. All ranks in the military and classes eight to one in the civil service endowed individuals with either personal or hereditary nobility. With rare exceptions, women did not serve in positions in the military or government that accorded them service rank, and therefore historians of the Russian nobility generally ignore noblewomen. A noblewoman’s rank derived first from her father’s rank and then from her husband’s, and her rank was in relation to her mother and later to other wives. However, in the Russian court that comprises the world of Catherine’s memoirs, noblewomen could acquire their own rank through serving in the personal courts of Empress Elizabeth and Grand Duchess Catherine.

2

Service rank visibly upheld the privileges of the nobility and distinguished nobles from non-nobles, in a period when nobility no longer depended solely on birth. The rules on rank governed all aspects of the appearance of nobles in public, from forms of address, access to events, and precedence, to clothing, carriages, and livery, with fines for acting or dressing above one’s rank.

3

Only certain informal occasions were declared rank-free, and Catherine composed her “Rules” to describe proper conduct at such a gathering. Otherwise, rank shaped all ceremonial activity at the court. In the memoirs, once Catherine becomes Grand Duchess, she supersedes her mother in rank, which creates friction between them. As Catherine explains in the final memoir, “My mother, whom I had always obeyed, did not see without displeasure that I preceded her, which I avoided everywhere that I could, but which was impossible in public.” According to both Catherine’s early and middle memoirs, the day after their arrival in Moscow on February 9, 1744, Empress Elizabeth I presented first Catherine and then her mother, Princess Johanna, with the Order of St. Catherine (41, 449). In contrast, the account that Princess Johanna wrote for her husband stresses that the Empress presented the order “to me first together with the star and afterward to my daughter.”

4

Status was integral to noble identity, especially at court, for women as well as men.

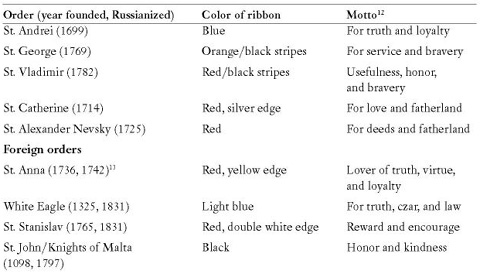

Beginning in 1699, upon his return from the Grand Embassy to Europe (1697–98), Peter the Great instituted chivalric orders, modeled on European orders, as rewards for service to the state. Like rank, orders were meant to connote individual merit through service, and to supplant a system of precedence through noble birth. The symbol of an order was a medal with a motto; the addition of diamonds and a wide, colored ribbon signified the highest degrees of these orders, with the first degree a ribbon worn over the shoulder, and the second degree a ribbon around the neck. Most orders had uniforms, anniversary gatherings, dues, pensions, charters that limited the number of members, and a chief knight. With the exception of the Order of St. Catherine, which was for women only (although Catherine I had awarded it to her favorite, Alexander Menshikov), with rare exceptions, all the orders were for men. Unlike rank, orders did not confer privileges, but orders correlated with ranks and thus might be accompanied by promotions in rank and position. In the memoirs, Catherine hints that her opponents have bought Lev Naryshkin’s loyalty with the inducement of getting the Order of St. Anna.

Details of Catherine’s coup in 1762 reveal the symbolic power of orders. On the eve of Catherine’s coup, the rumor that Peter III had presented his mistress, Elizabeth Vorontsova, with the Order of St. Catherine added urgency to Catherine’s decision to seize power. As Princess Ekaterina Dashkova (née Vorontsova, sister of Elizabeth) writes in her memoirs, the Order of St. Catherine could “be given only to members of the Imperial family and to princesses of foreign ruling houses, unless a woman had saved the ruler’s person or rendered a notable service to the nation.”

5

In other words, it signaled that Peter was preparing to depose Catherine and force her into a convent or prison, and make Elizabeth his consort. During the coup, as Catherine dressed to meet the guard regiments, she removed the Order of St. Catherine, which she then presented to Dashkova, who meanwhile procured for Catherine the blue ribbon of the Order of St. Andrei from Count Nikita Panin, which she then wore over her guard’s uniform. Again Dashkova explains that “the blue ribbon was not worn by the Emperor’s wife.” Thus it indicated that Catherine now ruled. Such details in portraits of the Russian nobility and royalty clearly had important state functions. Thus in the final memoir, in a verbal self-portrait, Catherine calls herself “an honest and loyal knight,” for she was a knight of the orders of St. Catherine, St. Andrei, St. George, and St. Vladimir.

Stepping outside this well-developed system of elite status, we find the undistinguished masses in three groups: merchants, clergy, and peasants and serfs. In the opening maxim of the memoir translated here, Catherine refers to the “common herd.” Her term in French,

le vulgaire,

refers to a traditional notion, the Greek

hoi polloi,

the Latin

profanum

or

ignobile vulgus

and

mobile vulgus,

or Shakespeare’s “beast with many heads.”

6

In this memoir, she illustrates her highly restricted view of society when she writes:

One of the masked balls was for the court alone and those whom the Empress deigned to admit; the other was for all the titled people in the city to the rank of colonel and those who served as officers in the guards. Sometimes the entire nobility and the wealthiest merchants were also permitted to come. The court balls did not exceed 150 to 200 people and those that were called public, 800 maskers.

In contrast to our understanding of the term “public” today, for Catherine it was limited to those who had the right to appear at court. It is worth remembering that when Catherine was writing these memoirs, French citizens had beheaded Louis XVI and American electors had elected their first president with 69 out of 138 votes. Catherine’s memoirs belong to a world of status and rank whose foundations were crumbling elsewhere, but which survived in Russia until 1917, and arguably survives there to the present day. Catherine’s era truly was the golden age of the nobility.

TABLE OF RANKS

The laws governing the Table of Ranks were periodically modified, and the simplified chart below represents the positions by class over the course of the eighteenth century.

7

Nineteen additional points to the Table of Ranks detail ranks for women, privileges, responsibilities, and punishments. Military ranks here correspond to those in the army. At the end of the eighteenth century, the complete table breaks down military ranks in the following order: guards (foot soldiers and cavalry), army (foot soldiers and cavalry), dragoons, Cossacks, artillery, and navy.

8

For example, the rank of major in the guards was two classes above that in the army (class 6 and class 8, respectively). Laws limited advancement by the number of places in each class and the minimum number of years someone had to spend in a class. It was possible to occupy a class above or below one’s profession, or service rank, and advance despite restrictions.

CHIVALRIC ORDERS

The orders are listed according to the general hierarchy of their importance; the complete list would include the degrees of each order in relation to each other.

11

Russia also added several foreign orders, some of which dated to the Crusades.

NOTES

Privileges included (1) the right to own land occupied by serfs (until their emancipation in 1861), (2) the right not to serve in the government or military (from 1762 to 1874, when universal military conscription became law) and preference in service for those who did serve, (3) freedom from corporal punishment (until 1863), (4) exemption from the poll tax (until 1883), (5) the right to be judged by peers (given to all Russians in judicial reforms of 1864, together with due process for life, status, and property), and (6) the right to travel abroad (restricted under Nicholas I). Paul I suspended the second and third privileges from 1796 to 1801, which led to his murder in 1801.

In 1725, at Peter the Great’s funeral, Catherine I’s ladies-in-waiting preceded the wives of men of the first eight ranks. Hughes,

Russia in the Age of Peter the Great,

194.

Ibid., 180–85. Sumptuary laws regulated, for example, the type of fabric and the width of lace, a luxury item, nobles of each rank were allowed to wear.

Anthony,

Memoirs,

81.

Princess Dachkova,

Mon histoire: mémoires d’une femme de lettres russe à l’époque des

Lumières,

ed. Alexander Woronzoff-Dashkoff, Catherine Le Gouis, and Catherine Woronzoff-Dashkoff (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1999), 44.

Barbara Ann Kipfer, ed.,

Roget’s International Thesaurus,

6th ed. (New York: Harper-Collins, 2001), 444 (606.2).

“Tabel’ o rangakh,” no. 3890, January 24, 1722,

Polnoe sobranie zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii,

1649–1913,

vol. 6 (St. Petersburg, 1830–1916), 486–93. The most recent full discussion of the Table of Ranks is L. E. Shepelev, Chinovnyi mir Rossii: XVIII-nachalo XIX v. (St. Petersburg: Iskusstvo-SPB, 2001). In English, Smith,

Love and Conquest,

403–4; Paul Dukes, trans. and ed.,

Russia Under Catherine the Great,

vol. 1 (Newtonville, Mass.: Oriental Research Partners, 1978), 4–14.