The Medieval English Landscape, 1000-1540 (7 page)

Read The Medieval English Landscape, 1000-1540 Online

Authors: Graeme J. White

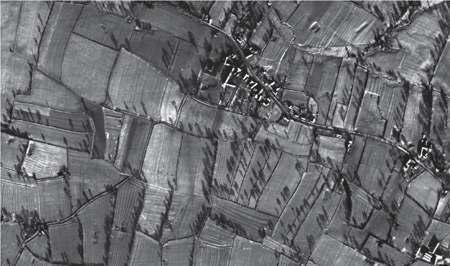

We may also be able to detect former arable strips in the landscape from a pattern of reverse-S hedges – planted in between the strips as part of the process of piecemeal enclosure – or from the zigzag course of a lane or boundary, which formerly marked the line of the headlands between the furlongs. There are few sequences of reverse-S hedges as spectacular as that at Brassington (Derbyshire), where the curving ridge and furrow can also be discerned in alignment with them, but field boundaries of this nature are widespread wherever the strips were enclosed by agreement between neighbours rather than through coercion or a commissioners’ award. As for zigzag lanes, an excellent illustration is to be found in the former Town Field area of Clotton (Cheshire) – shown as still partly ‘open’ on an estate map of 1734 – where the minor road known locally as ‘corkscrew lane’ plots a course between the surviving reverse-S field boundaries (

Figure 3

). Those who use such tracks today are quite literally following in the footsteps of the peasants who ploughed the fields on either side.

47

Figure 3: Field System, Clotton (Cheshire)

. This RAF photograph of January 1947 shows a small planned settlement along the main road (the A51) with a row of adjacent tofts, a back lane which then zigzags along the headlands of a former open field system, and several reverse-S hedges caused by the piecemeal enclosure of strips. (English Heritage NMR RAF Photography.)

Another feature of the modern rural landscape which may take us right back to the activities of these medieval farmers are lynchets (terraces on

hillsides where arable strips ran along the contours, rather than up and down the slope). These are normally interpreted as extensions to the open fields to feed a growing population, and they survive because they were allowed to revert to pasture in the population downturn of the late middle ages. Examples abound over much of the country, among the more readily accessible being the lynchets in the beechwoods of the Gog Magog hills of Shelford, south of Cambridge, those on the slopes below Housesteads Roman fort (Northumberland) and those associated with the deserted medieval settlement of Hound Tor on Dartmoor, where a sinuous reverse-S course can still be discerned. In a few places open arable strips are still being worked, though without the former communal regime – as at Soham (Cambridgeshire), 8 kilometres south-east of Ely, where the North Field was never enclosed, and the aforementioned Forrabury (Cornwall) (

Figure 1

).

48

However, the best demonstration of communal arable farming remains that at Laxton, where three great open fields are still worked by tenant farmers who hold intermingled strips, meet annually in early December in a manorial court (the Court Leet) presided over by the lord of the manor’s steward, and mostly live as neighbours to one another, in farms which line the main road through the village. Even so, as an echo of the medieval ‘midland system’, this demands qualification: each Laxton farmer now has the bulk of his land in enclosed fields outside the system of strips, the ‘fallow’ field grows a grass crop as forage for animals and in place of communal access to meadows the practice since 1730 has been for patches of common grassland (sykes) near watercourses to have their hay crops auctioned off to the highest bidder. Anyone with the slightest interest in medieval farming should visit Laxton, ideally between March and June when the strips are most easily distinguished: but what the visitor sees is not a fossilized open field system, but one which has evolved over the centuries as all such systems did. Laxton is special because of the remarkable survival of three open arable fields, albeit in truncated form, and of a court to regulate farming within them.

49

Medieval pastures took many different forms. Some were extensive areas of rough grazing on lightly settled moorlands and heathlands or were to be found in wetlands unsuitable for cultivation. Others were managed intensively by their local communities, among or beyond the arable fields, and were liable to be ploughed up if demand for arable outstripped supply. Some pastures served as greens around which settlements clustered. Yet others were temporary leys created within open arable fields, intended not only to feed

livestock but also to renew the fertility of the soil. Meadows, by contrast, had a more uniform appearance, normally fairly flat, located next to a watercourse and prone to flooding. By the time documentation becomes fairly abundant, it is clear that in all parts of the country some pasture and meadow was liable to be held in closes, managed exclusively for a lord or one of his acquisitive freeholders, and it is a measure of the importance of these resources – pastures for grazing and sometimes the collection of fuel, meadows for hay as winter feed – that such private holdings were often valued more highly than equivalent areas of arable: in the Essex manors of Latton and Bocking, for example, either side of the year 1300, while an acre (0.4 hectare) of arable was valued at sixpence (2.5p) per annum, private pasture was reckoned at a shilling (5p) per acre per annum and private meadow at two or four shillings. As with arable, however, at least a portion of the available pasture and meadow was normally managed in common, and where the ‘midland system’ prevailed it was fully integrated into the highly regulated regime, with livestock having to be moved on and off by appointed dates. The Bishop of Ely’s estate survey of 1251, for example, listed private and common resources separately, including at Little Gransden (Cambridgeshire) where there were 25 acres (10.1 hectares) of private pasture ‘called

Gravis

, where the plough-oxen of the parson of Gransden can feed with the bishop’s oxen’ along with ‘a certain pasture called

Langelund

, and it is common to all the village’. Similarly, on his manor of Barking (Suffolk), four areas of private pasture were listed, plus ‘a certain common of pasture which is called Berkingetye’ of 90 acres (36.4 hectares).

50

Barking Tye survives as a common to this day, governed by District Council bye-laws which forbid the posting of notices on trees, the snaring of birds and – except by ‘lawful authority’ which essentially was the case in the middle ages as well – the keeping on the common of cattle, sheep or other animals. Today, some 3% of the land surface of England is registered as common land, including precious survivals such as the Commons in south London – Clapham, Wandsworth, Tooting, Streatham – all saved ultimately because of acquisition by the Metropolitan Board of Works in the 1870s and 1880s and reminders of a string of discrete settlements, each of which had its own mention in the Surrey portion of Domesday Book.

Domesday was, however, inconsistent in its handling of pasture. Only one circuit, that covering south-west England, appears to have attempted systematic coverage, although fairly full details are given for some counties elsewhere. Measurements vary from acreages (often in round figures, like the 200 acres – about 81 hectares – of Lyneham, Oxfordshire) to linear estimates (such as 17 furlongs by 17 furlongs – about 3420 metres each way – at Frome, Dorset, or one league in length and breadth at King’s Nympton, Devon). Such differences make comparison very difficult, although Oliver Rackham has calculated that perhaps one-third of the landed area of

England was treated as pasture in 1086, if upland moors and heaths are included. Where a rental value is assigned, such as two shillings per annum at Kempston (Bedfordshire) or 40 pigs at Abinger (Surrey), it is possible that the reference is to privately held pasture, but this cannot be the case everywhere since at Oxford the burgesses paid 6s 8d (33.3p) per annum for what is specifically described as common pasture outside the town wall. There are several other explicit references to common pasture – in 12 places in Devon, for example – and its existence may also be inferred from use of the phrase ‘pasture for the livestock of the vill’, often found in Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire and Middlesex, or ‘pasture for sheep’ in East Anglia, especially Essex. Domesday also reveals that intercommoning arrangements between settlements were in place, usually so that those short of pasture could access that available elsewhere. Benton and Haxton (Devon) had common pasture in neighbouring Bratton Fleming; Hardington and Hemington (Somerset) used one another’s common pasture; there was pasture in the Suffolk hundred of Colneis common to all men of the hundred. It has also long been recognized that many of the ‘pasture for sheep’ entries for inland Essex manors were in fact referring to entitlements to graze the coastal marshes of Canvey, Foulness and Wallasea Islands.

51

The Domesday commissioners dealt more comprehensively with meadow than with pasture but inconsistencies in the way different Circuits handled their material again pose problems: most entries for meadow give their acreage, but others describe them by the number of plough teams they could sustain or use linear measurements. However, a more serious difficulty is the suspect nature of the information which is presented. Occasionally, we are specifically told that a manor had no meadow (as at Orwell Bury, Hertfordshire, or Stockton, Yorkshire), a circumstance which presumably meant resort to the intercommoning already encountered with pasture, but it is more usual to find cases where the resource is simply omitted. Accordingly, on the face of it there was no meadow at all in Shropshire (despite the richness of the Severn floodplain) and a paucity of it in the Welsh marches generally, in Cornwall and in much of East Anglia. It is impossible to believe that the royal manor of Hingham (Norfolk), with 60 villeins and 29 bordars holding 20 ploughs between them, had only 8 acres (3.2 hectares) of meadow, or that in Thetford, straddling the Little Ouse river which forms the boundary between Norfolk and Suffolk, a small portion in ecclesiastical hands had 12 acres (4.9 hectares) of meadow but the remainder, shared by king and earl, had none at all.

52

At Shocklach, a dispersed settlement in Cheshire adjoining the modern Welsh border, there is to this day a 16-hectare meadow still managed communally and until recently with boundary stones demarcating the ends of the surviving ‘doles’ or shares: this is appreciably more meadow than there apparently was in 1086, when only half an acre (0.2 hectares) was recorded (

Figure 4

).

53

Figure 4: Gwern-y-ddavid, Shocklach Oviatt (Cheshire)

. The meadow (bounded to the west by the Welsh border) still retains unenclosed ‘doles’ owned by different farmers, despite some consolidation since this photograph was taken in July 1971. As a township of dispersed settlement, Shocklach demonstrates communal farming of shared resources outside the context of a nucleated village. (Copyright 2006 Cheshire West and Chester Council & Cheshire East Council ©. All rights reserved. Flown and captured by Hunting Surveys Ltd., 8 July 1971.)

There is no certain answer to the conundrum, particularly since variation is apparent even within particular Domesday circuits: the Essex folios, for example, demonstrate that there were meadows in excess of 40 hectares for settlements in the north-west of the county watered by rivers such as the Stour and the Colne, but give much smaller amounts further down these rivers towards the east coast.

54

It may be that the management of grassland as meadow was not well-developed in some parts of the country, but it is also possible that what the Domesday commissioners were sometimes attempting to record was not the whole of a community’s meadow but a discrete portion of it, such as that held privately by the lord alone or (conversely) that held from him and subject to communal regulation. A focus on meadow shared as one of the assets of the manor might explain the contrast between north-west Essex where there were later to be some affinities to the ‘midland system’ and the rest of the county where there were not, and also the relative scarcity of recorded meadow in north-west Warwickshire where individual rather than communal holdings would later be much more significant than elsewhere in the midlands.

55

But it would be unwise to press this too hard and wrong to dismiss the Domesday figures altogether. Whatever vagaries there may have been in the collection and presentation of data, a striking contrast in the overall character of landscape

and economy is clearly apparent between Cornwall on the one hand, with its scattered references to odd acres of meadow, and the valley of the Thames with its tributaries in Oxfordshire and Berkshire on the other, rich in the extensive meadowland which helped to sustain a thriving medieval cheese-making industry.

56