The Maze of the Enchanter

Read The Maze of the Enchanter Online

Authors: Clark Ashton Smith

Tags: #Fantasy, #Short Stories, #Fiction

Volume Four of

The Collected Fantasies Of

C

lark

A

shton

S

mith

Edited by Scott Connors and Ron Hilger

With an Introduction by Gahan Wilson

Night Shade Books

San Francisco

The Maze of the Enchanter

© 2009 by The Estate of Clark Ashton Smith

This edition of

The Maze of the Enchanter

© 2009 by Night Shade Books

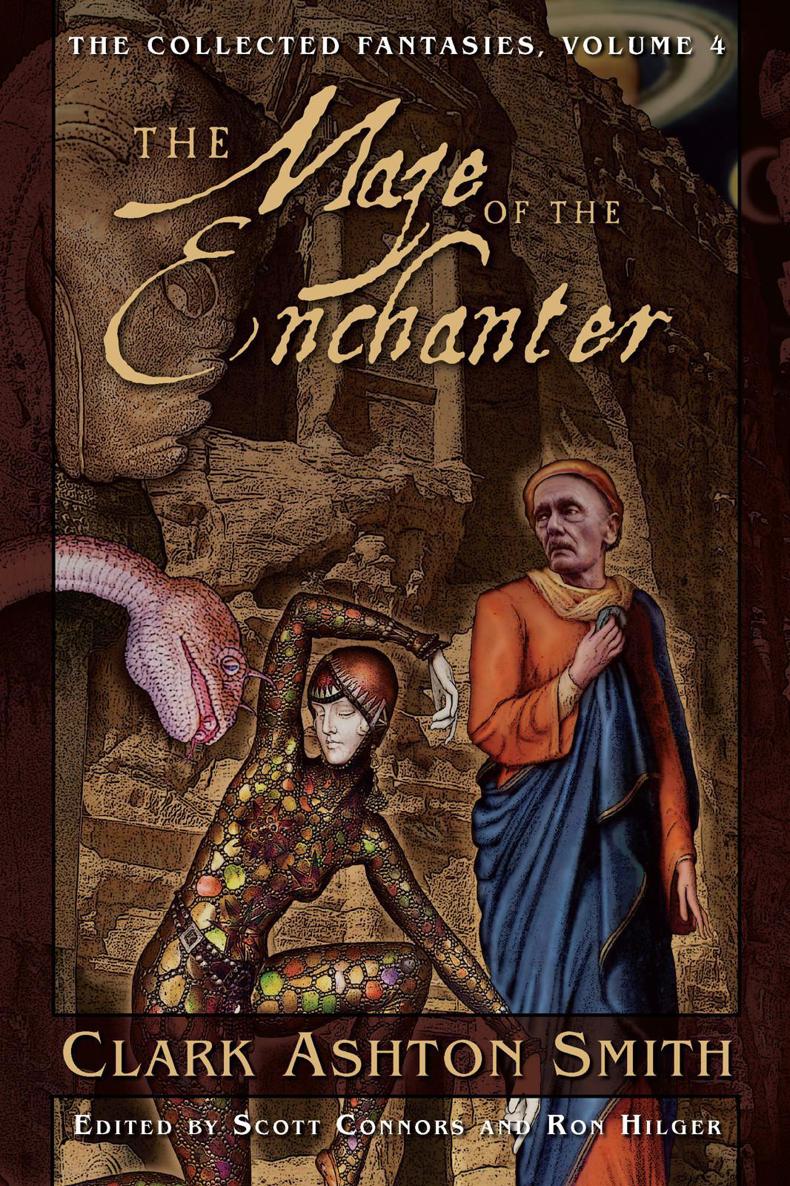

Jacket art © 2009 by Jason Van Hollander

Jacket design by Claudia Noble

Interior layout and design by Jeremy Lassen

Author photo by E. Hoffmann Price

Photo courtesy of David Drake and J. Daniel Price

All rights reserved.

Introduction © 2009 by Gahan Wilson

A Note on the Texts © 2009 by Scott Connors and Ron Hilger

Story Notes © 2009 by Scott Connors and Ron Hilger

Bibliography © 2009 by Scott Connors and Ron Hilger

First Edition

ISBN: 978-1-59780-031-0

Night Shade Books

Please visit us on the web at

http://www.nightshadebooks.com

I

NTRODUCTION

By Gahan Wilson

C

lark Ashton Smith’s works have always stirred me to the bones. His writings are both meticulously rendered and totally unabashed, his writings can be outrageously grotesque or exquisitely delicate or both simultaneously and without any clashing whatsoever. They are really and truly wonderful.

It took a lot of luck and considerable effort for me to track them down and delight in them, but once I finally came across the first I knew he was the real thing.

I was, frankly, an odd little kid who was always lured by the fantastic and the bizarre. I remember the thing I loved the most about the yearly visit of Barnum and Bailey’s big circus to Chicago was the freak show, and I would drag my father to its tent even though I knew he hated it.

Of course I also loved the acrobats and the band and the lion tamers, but they all had chosen to become what they now were whereas the grotesquely huge or absurdly tiny or horribly distorted or otherwise drastically different people of the freak show were born that way and had somehow managed not only to accept their condition fully and without reservation, they had the guts to stand on a platform before throngs of regular-sized, regular-looking folk and make it work for them.

I started my search for this kind of strangeness in art with the Sunday strips, mostly

Dick Tracy

with his ugly villains, but soon expanded the hunt by quietly plucking DC Comics from the magazine racks of the Evanshire Drugstore in Evanston, Illinois, and reading them for free with my small, bare elbows resting on the cool marble counter of the soda fountain while—on the really good days—I spooned and sucked away whole chocolate sodas as, with equal enthusiasm and greed, I read about the early doings of

Superman

and

Batman

and their multitudes of spectacular fiends and loved every crowded panel.

After that, I wandered further afield to the tiny little newsstand lurking beneath the elevated train’s Main Street Station in order to collect and soak up science fiction pulp magazines with their shamelessly gaudy covers featuring green and tentacled alien monsters which were all inexplicably but universally attracted to voluptuous Earth girls who had lots of curly hair and looks of horror on their faces.

I won’t pretend I didn’t enjoy all of this, but it turned out to be merely a gentle introduction to the glorious day when I worked up the nerve to go to a large and legendary newsstand a whole bus ride further away which was said to carry all kinds of usually unavailable magazines, and my eyes widened and my mouth fell open and joy flooded my heart when I spotted and began to thumb through my very first issue of

Weird Tales

magazine, a publication unashamedly and even proudly devoted to being creepy, and my life was never quite the same again.

Weird Tales

was, for a good part of Clark Ashton Smith’s life, his major source of income. It’s very true the relationship between Smith and the magazine was ever tricky and uneven and that its eccentric and autocratic editor, Farnsworth Wright, was guilty of highhandedly insisting on many alterations and eliminations which were hurtful to both the works and their creators (do note that the producers of this series of Smith’s manuscripts have worked scholarly wonders to correct as many of these ill-advised “corrections” as possible), but without that same editor’s initial OKs on Smith’s stories the great bulk of the tales in these marvelous Night Shade collections would never have been written. Life is complicated.

One very important, if somewhat odd, requirement about creating really good fantasy is that it must be solidly based on reality, and though Clark Ashton Smith was about as romantic as a romantic could get and very gentle with his fellow humans, he was also an astute and occasionally merciless viewer of life and his species and their many failings, and his stories are very often wise teachings as well as entertainments.

I suggest, if you are a Smith beginner, it might be a good idea to start your reading of this book with its title tale—“The Maze of the Enchanter”—as I believe it is a particularly good example of the bizarre startlements, subtly unveiled richnesses and the deeply ironic humor of a great, eccentric artist in top form who is enjoying himself enormously.

At the end of this unabashedly affectionate salute to a man to whom I owe so much, I would like to leave you with a story about Clark Ashton Smith which I deeply treasure. I don’t know where I read it, doubtless in something printed by Arkham House, one of Smith’s most true-blue supporters, possibly in the little magazine good old August Derleth put out for some years toward the end.

A group of Smith’s fans had written the author to ask if he would be kind enough to let them visit him while traveling in the West, and he not only wrote a note saying he’d be delighted to do so, he drew them a little map showing them how to make their way to his secluded cabin.

They were driving in their car, close to their goal, when they came to a fork in the narrow road which was not indicated on the map and they stopped and were puzzling what they should do next when one of them rose in his seat and pointed out the figure of a man climbing down the mountain slope to their left. They peered at him and saw that he was carrying a sign set on a small post. The sign was shaped like an arrow and it pointed at the man’s back and it had CLARK ASHTON SMITH written on it in big bold letters. Of course Smith was on his way to stick it into the ground at the intersection.

I don’t know about you, but this story warmed my heart when I first read it, and it still does now that I write it out.

A

N

OTE ON THE

T

EXTS

C

lark Ashton Smith considered himself primarily a poet and artist, but he began his publishing career with a series of Oriental

contes cruels

that were published in such magazines as the

Overland Monthly

and the

Black Cat

. He ceased the writing of short stories for many years, but under the influence of his correspondent H. P. Lovecraft he began experimenting with the weird tale when he wrote “The Abominations of Yondo” in 1925. His friend Genevieve K. Sully suggested that writing for the pulps would be a reasonably congenial way for him to earn enough money to support himself and his parents.

Between the years 1930 and 1935, the name of Clark Ashton Smith appeared on the contents page of

Weird Tales

no fewer than fifty-three times, leaving his closest competitors, Robert E. Howard, Seabury Quinn, and August W. Derleth, in the dust with forty-six, thirty-three and thirty stories, respectively. This prodigious output did not come at the price of sloppy composition, but was distinguished by its richness of imagination and expression. Smith put the same effort into one of his stories that he did into a bejeweled and gorgeous sonnet. Donald Sidney-Fryer has described Smith’s method of composition in his 1978 bio-bibliography

Emperor of Dreams

(Donald M. Grant, West Kingston, R.I.) thus:

First he would sketch the plot in longhand on some piece of note-paper, or in his notebook,

The Black Book

, which Smith used circa 1929-1961. He would then write the first draft, usually in longhand but occasionally directly on the typewriter. He would then rewrite the story 3 or 4 times (Smith’s own estimate); this he usually did directly on the typewriter. Also, he would subject each draft to considerable alteration and correction in longhand, taking the ms. with him on a stroll and reading aloud to himself [. . .]. (19)

Unlike Lovecraft, who would refuse to allow publication of his stories without assurances that they would be printed without editorial alteration, Clark Ashton Smith would revise a tale if it would ensure acceptance. Smith was not any less devoted to his art than his friend, but unlike HPL he had to consider his responsibilities in caring for his elderly and infirm parents. He tolerated these changes to his carefully crafted short stories with varying degrees of resentment, and vowed that if he ever had the opportunity to collect them between hard covers he would restore the excised text. Unfortunately, he experienced severe eyestrain during the preparation of his first Arkham House collections, so he provided magazine tear sheets to August Derleth for his secretary to use in the preparation of a manuscript.

Lin Carter was the first of Smith’s editors to attempt to provide the reader with pure Smith, but the efforts of Steve Behrends and Mark Michaud have revealed the extent to which Smith’s prose was compromised. Through their series of pamphlets, the

Unexpurgated Clark Ashton Smith,

the reader and critic could see precisely the severity of these compromises; while, in the collections

Tales of Zothique

and

The Book of Hyperborea

, Behrends and Will Murray presented for the first time these stories just as Smith wrote them.

In establishing what the editors believe to be what Smith would have preferred, we were fortunate in having access to several repositories of Smith’s manuscripts, most notably the Clark Ashton Smith Papers deposited at the John Hay Library of Brown University, but also including the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley; Special Collections of Brigham Young University; the California State Library; and several private collections. Most of the typescripts available are carbon copies; where possible, we also consulted the original manuscript appearance of the story, since Smith occasionally would pencil in a change to the top copy of the typescript that did not get recorded on the carbons. Priority was given to the latest known typescript prepared by Smith, except where he had indicated that the changes were made solely to satisfy editorial requirements. In these instances we compared the last version that satisfied Smith with the version sold. Changes made include the restoration of deleted material, except only in those instances where the change of a word or phrase seems consistent with an attempt by Smith to improve the story, as opposed to the change of a word or phrase to a less Latinate, and less graceful, near-equivalent. This represents a hybrid or fusion of two competing versions, but it is the only way that we see that Smith’s intentions as author may be honored. In a few instances a word might be changed in the Arkham House collections that isn’t indicated on the typescript. As discussed below, “The Beast of Averoigne” is one such example.