The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World* (15 page)

Read The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World* Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #Retail, #Ages 10+

BOOK: The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World*

7.51Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

But now it was time for Massasoit to visit the English himself. He had to turn to squanto.

Â

âââ On March 22, five days after his initial visit, samoset returned to Plymouth with four other Indians, squanto among them. squanto spoke about places that now seemed like a distant dream to the Pilgrimsâbesides spending time in spain and Newfoundland, squanto had lived in the Corn Hill section of London. The Indians had brought a few furs to trade, along with some fresh herring. But the real purpose of their visit was to inform the Pilgrims that Massasoit and his brother Quadequina were nearby. About an hour later, the sachem appeared on Watson's Hill with a large entourage of warriors.

The Pilgrims described him as “a very lusty [or strong] man, in his best years, an able body, grave of countenance, and spare of speech.” Massasoit stood on the hill, his face painted dark red, his entire head glistening with bear grease. Draped around his neck were a wide necklace made of white shell beads and a long knife hanging from a string. His men's faces were also painted, “some black, some red, some yellow, and some white, some with crosses, and other antic works.” some of them had furs draped over their shoulders; others were naked. But every one of them possessed a stout bow and a quiver of arrows. These were unmistakably warriors: “all strong, tall, all men in appearance.” Moreover, there were sixty of them.

â

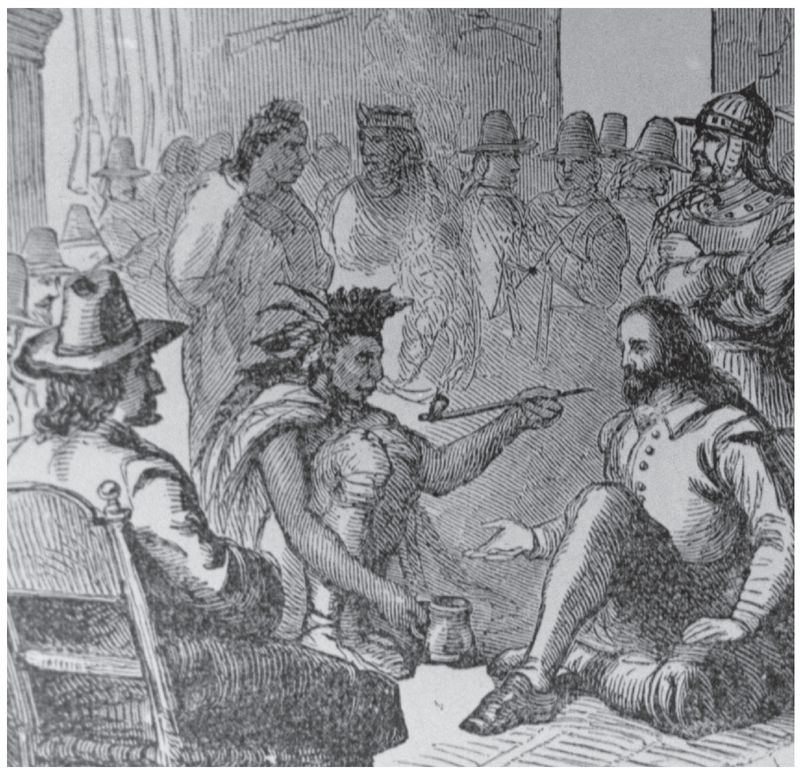

Nineteenth-century engraving of the first peace treaty between Governor Carver and Massasoit.

Nineteenth-century engraving of the first peace treaty between Governor Carver and Massasoit.

For the Pilgrims, who could not have gathered more than twenty adult males and whose own military leader was not even five and a half feet tall, it must have been a most intimidating display of physical strength and power. squanto ventured over to Watson's Hill and returned with the message that the Pilgrims should send someone to speak to Massasoit. Edward Winslow's wife, Elizabeth, was so sick that she would be dead in just two days, but he agreed to act as Governor Carver's messenger. Clad in armor and with a sword at his side, he went with squanto to greet the sachem.

First he presented Massasoit and his brother with a pair of knives, some copper chains, some alcohol, and a few biscuits, “which were all willingly accepted.” Then he delivered a brief speech. King James of England saluted the sachem “with words of love and peace,” Winslow proclaimed, and looked to him as a friend and ally. He also said that Governor Carver wished to speak and trade with him and hoped to establish a formal peace. Winslow was under the impression that squanto “did not well express it,” but Massasoit seemed pleased. The sachem ate the biscuits and drank the liquor, then asked if Winslow was willing to sell his sword and armor. The Pilgrim messenger politely declined. It was decided that Winslow would remain with Quadequina as a hostage while Massasoit went with twenty of his men, minus their bows, to meet the governor.

Captain standish and half a dozen men armed with muskets met Massasoit at the brook. They exchanged greetings, and after seven of the warriors were designated as hostages, standish accompanied Massasoit to a house, still under construction, where a green rug and several cushions had been spread out on the dirt floor. On cue, a drummer and trumpeter began to play as Governor Carver and a small parade of musketeers made their way to the house.

Upon his arrival, Carver kissed Massasoit's hand; the sachem did the same to Carver's, and the two leaders sat down on the green rug. It was now time for Massasoit to share in yet another ceremonial drink of liquor. Carver took a swig of aqua vitae and passed the cup to Massasoit, who took a large gulp and broke into a sweat. As the meeting continued, during which the two groups worked out a six-point agreement, Massasoit was observed to tremble “for fear.”

Instead of Carver and the Pilgrims, it may have been Massasoit's interpreter who caused the sachem to shake. The Pilgrims later learned that squanto claimed they kept the plague in barrels buried beneath their storehouse. The barrels actually contained gunpowder, but the Pilgrims undoubtedly guarded the storehouse, which made squanto's claims believable. If the interpreter told Massasoit of the deadly contents of the barrels during the meeting on March 22, it is little wonder Massasoit was seen to tremble.

Bradford and Winslow recorded the agreement with the Pokanoket sachem as follows:

1. That neither he nor any of his should injure or do hurt to any of our people.

2. And if any of his did hurt to any of ours, he should send the offender, that we might punish him.

3. That if any of our tools were taken away when our people were at work, he should cause them to be restored, and if ours did any harm to any of his, we would do the like to him.

4. If any did unjustly war against him, we would aid him; if any did war against us, he should aid us.

5. He should send to his neighbor confederates, to certify them of this, that they might not wrong us, but might be likewise comprised in the conditions of peace.

6. That when their men came to us, they should leave their bows and arrows behind them, as we should do our pieces when we came to them.

Once the agreement had been completed, Massasoit was escorted from the settlement, and his brother was given a similar reception. Quadequina quickly noticed something that his higher-ranking brother had not chosen to comment on. Even though the Indians had been required to lay down their bows, the Pilgrims continued to carry their musketsâa clear violation of the treaty they had just signed with Massasoit. Quadequina “made signs of dislike, that [the guns] should be carried away.” The English could not help but admit that the young Indian had a point, and the muskets were put aside. squanto and samoset spent the night with the Pilgrims while Massasoit and his men, who had brought along their wives and children, slept in the woods, just a half mile away. Massasoit promised to return in a little more than a week to plant corn on the southern side of Town Brook. squanto, it was agreed, would remain with the English. As a final gesture of friendship, the Pilgrims sent the sachem and his people a large kettle of English peas, “which pleased them well, and so they went their way.”

After almost five months of uncertainty and fear, the Pilgrims had finally established diplomatic relations with the Native leader who, as far as they could tell, ruled this portion of New England. But as they were soon to find out, Massasoit's power was not as widespread as they would have liked. The Pokanokets had decided to align themselves with the English, but many of Massasoit's allies had yet to be convinced that the Pilgrims were good for New England.

The next day, squanto left to fish for eels. At that time of year, the eels lay sleeping in the mud, and after wading out into the cold water of a nearby tidal creek, he used his feet to “trod them out.” By the end of the day, he returned with so many eels that he could barely lift them all with one hand. That night the Pilgrims ate the eels happily, praising them as “fat and sweet,” and squanto was on his way to becoming the one person in New England they could not do without.

Â

âââ Two weeks later, on April 5, the

Mayflower,

her empty hold filled with stones from the Plymouth Harbor shore to replace the weight of the unloaded cargo, set sail for England. Like the Pilgrims, the crew had been cut down by disease. Jones had lost his boatswain, his gunner, three quartermasters, the cook, and more than a dozen sailors. He had also lost a cooper, but not to illness. John Alden had decided to stay in Plymouth.

Mayflower,

her empty hold filled with stones from the Plymouth Harbor shore to replace the weight of the unloaded cargo, set sail for England. Like the Pilgrims, the crew had been cut down by disease. Jones had lost his boatswain, his gunner, three quartermasters, the cook, and more than a dozen sailors. He had also lost a cooper, but not to illness. John Alden had decided to stay in Plymouth.

The

Mayflower

made excellent time on her voyage back across the Atlantic. The same winds that had battered her the previous fall now pushed her along, and she arrived at her home port of Rotherhithe just down the Thames River from London, on May 6, 1621âless than half the time it had taken her to sail to America. Master Jones learned that his wife, Josian, had given birth to a son named John. soon enough, Jones and the

Mayflower

were on their next voyage, this time to France for a cargo of salt.

Mayflower

made excellent time on her voyage back across the Atlantic. The same winds that had battered her the previous fall now pushed her along, and she arrived at her home port of Rotherhithe just down the Thames River from London, on May 6, 1621âless than half the time it had taken her to sail to America. Master Jones learned that his wife, Josian, had given birth to a son named John. soon enough, Jones and the

Mayflower

were on their next voyage, this time to France for a cargo of salt.

Perhaps still suffering the effects of that awful winter in Plymouth, Jones died on March 5, 1622, after his return from France. For the next two years, the

Mayflower

lay idle, not far from her captain's grave on the banks of the Thames. By 1624, just four years after her historic voyage to America, the ship had become a rotting hulk. That year, she was found to be worth just £128 (roughly $24,000 today), less than a sixth of her value back in 1609. Her subsequent fate is unknown, but she was probably broken up for scrap, the final casualty of a voyage that had cost her master everything he could give.

Mayflower

lay idle, not far from her captain's grave on the banks of the Thames. By 1624, just four years after her historic voyage to America, the ship had become a rotting hulk. That year, she was found to be worth just £128 (roughly $24,000 today), less than a sixth of her value back in 1609. Her subsequent fate is unknown, but she was probably broken up for scrap, the final casualty of a voyage that had cost her master everything he could give.

Â

âââ Soon after the

Mayflower

departed for England, the shallow waters of Town Brook became alive with fish. Two species of herringâalewives and bluebacksâreturned to the fresh waters where they had been born in order to reproduce.

Mayflower

departed for England, the shallow waters of Town Brook became alive with fish. Two species of herringâalewives and bluebacksâreturned to the fresh waters where they had been born in order to reproduce.

squanto explained that these fish were essential to planting a successful corn crop. Given the poor quality of the land surrounding Plymouth, it was necessary to fertilize the soil with dead herring. Although Native women were the ones who did the farming (with the sole exception of planting tobacco, which was considered men's work), squanto knew enough of their techniques to give the Pilgrims a crash course in Indian agriculture.

The seed the Pilgrims had stolen on the Cape is known today as northern flint corn, with kernels of several colors, and was called

weachimineash

by the Indians. Using mattocksâhoes with stone heads and wooden handlesâthe Indians gathered mounds of earth about a yard wide, where several fish were included with the seeds of corn. Once the corn had sprouted, beans and squash were added to the mounds. The vines from the beans attached to the growing cornstalks, creating a blanket of shade that protected the plants' roots against the hot summer sun while also keeping out weeds. Thanks to squanto, the Pilgrims' stolen corn thrived, while their own barley and peas suffered in the soil of the New World.

weachimineash

by the Indians. Using mattocksâhoes with stone heads and wooden handlesâthe Indians gathered mounds of earth about a yard wide, where several fish were included with the seeds of corn. Once the corn had sprouted, beans and squash were added to the mounds. The vines from the beans attached to the growing cornstalks, creating a blanket of shade that protected the plants' roots against the hot summer sun while also keeping out weeds. Thanks to squanto, the Pilgrims' stolen corn thrived, while their own barley and peas suffered in the soil of the New World.

â

Corn that was called

weachimineash

by the Wampanoags, or northern flint corn today.

Corn that was called

weachimineash

by the Wampanoags, or northern flint corn today.

In April, while laboring in the fields on an unusually hot day, Governor Carver began to complain about a pain in his head. He returned to his house to lie down and quickly lapsed into a coma. A few days later, he was dead.

After a winter of so many secret burials, the Pilgrims laid their governor to rest with as much pomp and circumstance as they could musterâ“with some volleys of shot by all that bore arms.” Carver's brokenhearted wife followed her husband to the grave five weeks later. Carver's one surviving male servant, John Howland, was left without a master; in addition to becoming a free man, Howland may have inherited at least a portion of Carver's estate. The humble servant who had been pulled from the ocean a few short months ago was on his way to becoming one of Plymouth's foremost citizens.

Other books

Flight by GINGER STRAND

Forget You Had a Daughter - Doing Time in the Bangkok Hilton by Sandra Gregory

King Charles II by Fraser, Antonia

Doomsday Love: An MMA & Second Chance Romance by Shanora Williams

Mistaken Identity by Montgomery, Alyssa J.

The Tunnel Rats by Stephen Leather

Dragonfriend by Marc Secchia

Through Glass Darkly Episode 1 by Peter Knyte

High Spirits at Harroweby by Comstock, Mary Chase

The Circle Now Is Made (King's Way Book 1) by Mac Fletcher