The Mascot (38 page)

Authors: Mark Kurzem

Dina and Erick exchanged words in a language that was not Russianâperhaps it was a Belarusian dialectâbut it was obvious that there was tension between them, perhaps because Erick had not told her anything about us beforehand.

I stepped in. “May we see inside the house?” I asked Dina.

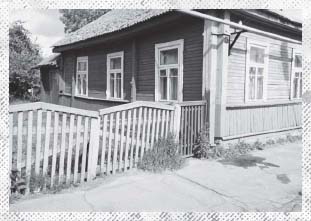

My father's orignal home at 12 October Street in Koidanov.

The door squeaked open on its rusting hinges.

I followed behind my father and mother as they tentatively entered the run-down kitchen, which appeared not even to have running water.

“When I bought this house it was deserted,” Dina said self-consciously, “and in even worse condition than it is now.”

We moved deeper into the house, which consisted of two other rooms. Both were bare of furnishings apart from a solitary chair and a small divan. My father looked around.

“Do you remember this room?” I asked.

“This might have been where I slept⦔ He shifted the chair from its position by the window and stood where it had been.

“The bed would've been here,” he said. “I was lying with my head at this end on the night my father said good-bye to me. The dividing curtain must have been over there. Later, I would've seen him leave that way, over there, through the door.” My father pointed directly at the main door we'd just entered through, visible in the kitchen on the far side of the house. He stared up at the ceiling.

“My father's feet would've been dangling just over there.”

I went over to inspect the ceiling. There was evidence of a trapdoor to the roof space that had been boarded up. My father joined me to inspect it. He noticed something else.

“Look,” he said, pointing off to the right. There was a row of about a dozen rusted hooks that had been nailed into a ceiling beam. “Yes.” My father nodded. “They could've been used to hang a curtain.

“And when I came to the curtain to eavesdrop on my parents, they were sitting at a table there.” My father pointed in the direction of the kitchen.

Dina, who had been watching and listening intently to my father, added that in fact there had been a table there when she'd moved into the house.

“Isn't that correct?” she said, turning to Erick, who'd been strangely silent.

“Yes,” he replied uncomfortably.

It seemed as if the layout of the house coincided with my father's memories.

“So

this

was the Galperin house,” he said. As if reading my mind at that moment, I heard my father's voice. “From before the war.”

“Yes,” Erick said.

“I grew up here?”

“Yes.”

“I have another memory,” my father said, “of a soldier coming into this room. Not a Nazi. A friendly one.” My father squinted, trying to remember more. “He was visiting a lady, not my mother, but another who lived with us, I think.”

“That must have been your aunt Sonya, Solomon's sister,” Erick replied. “She did live here. She died with the rest of the family. She was engaged to a Russian soldier who was sent to the front. Nobody knew what became of him. He never came looking for Sonya after the war. He must have perished, too.”

“Can you think of anything else about the history of the house or the family?” I asked.

A likely image of Hana Galperin, my father's mother, found in a dusty bag of photographs in the old family home in Koidanov.

Erick shook his head, as did Dina, but suddenly her expression changed. “One moment. There is something⦔

Dina crossed to the divan and began to rummage underneath it. “I forgot. Last year, some of the floor had to be replaced. The carpenter found it hidden there. I meant to tell you, Erick. Sorry, I forgot.”

We waited expectantly. She rose with something in her hand. “These.”

She dusted off a plastic bag and held it aloft. “Old photos,” she declared. “I don't know who the people are. You are welcome to look.”

I reached for the bag and sat down on the one chair in the room, removing a handful of photos. I flipped slowly through faded pictures of individual faces and family group portraits. It was difficult to say when these had been taken, but they likely predated the war. Judging by their garb, some of the people were Jewish. One particular photograph of a young woman gave me pause. Smiling confidently at the camera, she was in her early twenties and had an attractive and open face. She was dressed up in her finest and may have been off to a special occasion. I had no idea who she was and passed the photograph to my father. He shook his head.

Father and son outside the family home in Koidanov, 1998.

I returned the photographs to the bag and removed another handful, which I began to go through before passing them on to my father. Suddenly I stopped, transfixed. The photograph I held had been partly torn so that its top right corner was missing, but one side of the face of another young woman was still clearly visible.

“It's Krystal,” I gasped. Whoever this woman staring intently into the camera was, she was identical to my niece, my brother Andrew's daughter.

My father reached across for the photograph. I was still dazed but I heard him say, “Oh my God,” and then pass it to my mother, who similarly exclaimed, wanting to know what a photograph of her teenage granddaughter was doing among these faces from the past.

We were silent, overwhelmed by what we'd just seen.

My mother spoke first, clearing her throat. “The eyes,” she said. “And the shape of the face. She's so like Krystal, isn't she?”

“Uncanny,” my father replied.

“She must be related to us somehow,” I said. “Who is she?” I passed the photograph to Erick. He examined it closely.

“It might be Hana, your mother,” he replied. “But I'm not certain. I only saw one photograph of her one time.” Erick returned the picture to my father.

“Do you remember this face?” my mother asked gently, looking over her husband's shoulder.

“No,” he answered. “But it's so like Krystal, it must be someone close to me. My mother? I must be Ilya Galperin. I believe it.” He shook his head.

We were all infected by his sense of astonishment. How could a man with only those two mysterious wordsâ“Panok” and “Koidanov”âhave found his way home nearly sixty years later to the room where he had slept as a child in the company of his baby sister and younger brother, to the place where he had been nurtured by his mother and father before the Nazis tore them apart?

I followed my father and the others as they made their way back up the driveway toward the blue bus. I stared at my father's back. He was hunched forward, carrying the bag of photographs that Dina had given to him as a gift. Such a gift. He was still shaking his head in amazement.

SOLOMON AND VOLODYA

I

t was late afternoon, but the day wasn't over for us. Erick wanted us to meet an old, dear friend of Solomon's. He'd been sullen since we'd discovered Solomon and Hana's house.

The bus rattled to a halt outside a run-down cottage: paint was peeling from its walls and the shutters on the windows swung loosely on their hinges. Erick, who had been riding up front with the driver, turned to look at us.

“We are at the house of Volodya Katz,” he said. “My father's best friend from before the war up until he died.” Erick was the first out of the bus and waited for us to join him. “I'm sorry,” he said, “but Volodya can only meet Alex and Mark, and, of course, Galina to translate.”

“Why can't Patricia come?” my father protested.

“Volodya is uncomfortable with having too many people in his humble surroundings,” Erick explained.

“Don't worry,” my mother said. “I can take a nap while you're gone.”

We passed through a gap in the fence where a gate had once been and made our way along a path to the house. Before we'd even reached the front door, it opened, and a very elderly woman appeared on the veranda. Beside her, holding her hand, was an equally aged man with startling blue eyes that seemed to look through us. He raised his hand in the air and called out, “Shalom! Ilya Solomonovich!”

“Shalom!” my father responded.

We climbed the steps up to the veranda, where Volodya stood with his arms outstretched. He embraced my father awkwardly. It was then that I realized he was blind.

“Ilya Solomonovich.” Volodya wept at the words. “Ilya Solomonovich.”

“Yes, yes, that's me,” my father answered slightly self-consciously. It would take some time for “Ilya Galperin” to sit comfortably with him. “This is my son Mark,” he said quickly.

Volodya beckoned me toward him. He gripped me strongly by my shoulders and appeared to take my measure intuitively.

“My wife, Anya,” Volodya said as the woman behind him stepped forward and greeted each of us. Although she was well into her eighties, one could tell that she was a woman of character. She still had piercing and decisive eyesâshe must have been handsome and charismatic as a young woman. She took my father by one hand and Volodya by the other and guided them into the house while we followed behind.

The room was dark and sparsely furnished with a few shabby pieces. There didn't seem to be any heating apart from a small brick stove. The floor covering was pitted and buckled linoleum. The couple seemed to live only in this room, and in the far corner there were two bunk beds made out of wooden planks with thin blankets strewn over them. The table had been set for a modest tea, which Anya served while Volodya began to speak.

“I could not believe my ears,” he said, shaking his head, “when Erick told me that Solomon's boy had been found alive. In Australia!”

My father smiled. “You knew my father well?” he asked.

“Your father and I were good friends all our lives. We were the same age. We grew up together in this village. Even after your father married Hana, and I, Anya, we remained close. We were always at their house on October Street.”

Anya nodded. “Your mother was an excellent cook,” she said. “She could make a feast out of nothing.”

“What was my mother like?” my father asked.

“She was very gentle,” Anya said, wiping her hands on her apron. “She was young. She must have married your father when she was about sixteen. That was the custom in those days. Solomon was older than herâhe must have been about twenty-one. They were a lovely couple and even though a matchmaker had been involved, they cared for each other. You could see it in the way they were when they were together.”

My father leaned forward, hanging on Anya's every word.

“She showered so much love on you and your brother and sister.”

“Do you remember me?” my father asked.

“Of course I do,” Anya replied. “I used to nurse you when you were a baby. When you got older you loved to sit on my lap. Not as much as you loved to sit on your aunt Sonya's. You were the apple of her eye. She was your father's sister. A real beauty. She lived with your family. Your mother and Sonya were great friends. They'd known each other all their brief lives, too. She'd been planning to get married to a Russian soldierâ”

My father interrupted, exclaiming, “I mentioned that before. I have a memory of a man in a uniform.”

“Sergei was his name,” Anya said. “He was very quick-witted and charming. He'd make us all laugh when he was there. Do you remember Aunt Sonya?”

My father shook his head.

“You don't remember her singing to you?”

“Not at all.”

Anya paused. She'd noticed my father's mood darken at her last comment. “As you got older you didn't want to sit on my knee anymore. You'd wriggle away from me and stand with your hands on your hips, telling me that you had business in the village. You'd make all of us laugh out loud with your antics. You were quite the man about town. Everybody in the village knew you. You'd talk to anyoneâthe policeman, the baker, anyone. You'd have a word for them all. You were a good boy. You had a kind nature. You were always considerate. Helping the old people in the village, chatting away to them.”

My father shook his head, laughing. He was both moved and embarrassed. “I had no idea I was such an angel.” He feigned surprise.

“Oh, but you weren't,” Anya joked. “You were a rascal, too, especially when you were out and about with one of those boys. What was their name?”

She paused.

“Panok,” she said, clapping her hands together. “Now those boys were trouble. Always up to mischief and trying to involve you.”

“Panok!” my father exclaimed, almost jumping out of his chair with excitement.

“There was one your age. The pair of you were inseparable. You'd have your arms around each other's shoulders as you walked around the village. You both loved playing in the apple tree behind your house.”

“That's right,” my father said. His face was bright red and his blue eyes shone with pleasure and emotion. “We used to play pirates in the apple tree. One of us would climb up to the top and act as a lookout and report on the pirates about to invade our village.”

My father turned to look at me. “So that was the answer all along,” he said. “Panok was my best friend.” My father touched Volodya's arm.

“Tell me, do you know what became of him?”

“He perished that day,” Volodya replied. “With the rest of his family.”

My father sank back into his seat, defeated. “And none of them survived?” he said.

Volodya shook his head.

The mystery of Panok had been solved, and although he didn't remember it, I realized that my father had likely witnessed the extermination of his dear friend, also only five, that day.

Anya poured more coffee.

After some time my father spoke again.

“Do you remember my birthday?” he asked.

“It may have been late in 1935,” Anya answered. “But I can't say for certain.”

“What about my little brother and sister, do you remember them?”

“Very little. By that time, I was spending more time in Leningrad with my sister, who was unwell. I returned to the village occasionally, but there were few chances to meet with Solomon and Hana.”

“Do you remember?” Anya asked her husband.

“The little girlâ¦no. But the boy was perhaps called David. You were definitely Ilya. Named after your grandfather, who was also Ilya. A tradition among us Jews.”

I looked at Volodya and noticed that there were tears in his eyes.

“I miss our village,” he said. “It was a true shtetl. Of course, there were the usual fallings-out and scandals, but people looked after each other. That's all gone now.”

Volodya wiped his cheeks. “When I finally reached home after the war I was told that every single Jewish soul had perished.” His large, bearlike hand reached for Anya's.

“We didn't even know that each other had survived then,” Anya said.

Volodya nodded grimly. “I'd made my way through the forests to the northeast of Belarus,” he said, “and when I got back the village was almost deserted. Fortunately this place was still standing, but it was in bad condition. I set about repairing it and, one day, when I was on the roof, I saw Anya coming along the path. I rubbed my eyes to make sure I wasn't dreaming. Anya had survived.”

“You are both survivors,” my father said.

“We were fortunate,” Volodya said. “Anya was in Leningrad with her sister when Belarus was invaded. She stayed there and later joined the partisans.”

“And what about you?” my father asked Volodya.

“I joined the partisans, too. Outside Mogilev in the northeast of Belarus.”

“And my father?”

“Your father was a survivor, too.”

“My mother told me that my father was dead. Why would she have done that?”

“So that you wouldn't have given the game away,” Volodya replied.

My father gave him a puzzled look, forgetting that the man was blind.

Solomon and his friend Volodya, with whom he escaped from Koidanov in 1941.

“Weâyour father and Iâdidn't want anybody, including you, to know where we were hiding,” Volodya said.

“I don't understand,” my father said.

“Let me start at the beginning,” Volodya said. “The Fascists invaded our country in 1941. There'd been scraps of news and rumors that the Nazis were rounding up the men and boys from the villages and taking them away. We knew what that meantâit was going to be like the old days of the pogroms. None of the Jews in the village knew what to make of it. But we were sure that the elderly, the women, and the children would be safe. We knew that if the Nazis came into Koidanov we'd be done for. Some of the other men in the village were also making plans to get away before the Fascists arrived. There was a lot of talk about joining the partisans that were forming in the forests everywhere throughout Belarus. A few men talked about heading farther east away from the invaders.

“In late summer of 1941,” Volodya recalled, “I visited your parents to discuss the situation. I put it to Solomon that we, too, should think about escaping. He was reluctant.

“âAnd my family?' your father said. âMy children? What about them?'

“I had to convince him of the danger to both of us. âThe Germans aren't coming for the women and children,' I told your father. âThey'll be safe if they keep to themselves.' Your father knew the history of the pogroms, after all. But he couldn't be convinced that this was the best course of action.

“I had another idea. Anya was already in Leningrad with her sister. I told Solomon and Hana that I'd hide in the roof of my house but spread the word that I'd joined the partisans.

“âRidiculous!' Solomon said. âHow will you survive up there?'

“âI'll store food and water with me and anything else, then I'll wait until the middle of the night,' I told Solomon.

“Suddenly we heard a noise and jumped up. Somebody had been listening to our plans. Do you know who it was?”

My father shook his head.

“You.” Volodya laughed. “You'd been eavesdropping from behind the curtain.

“Your mother ordered you back to bed, but you didn't want to go. You were stubborn, that's for sure.”

“I remember a scene like that. The talk had woken me up. Wait!” My father stopped abruptly. “Did you have a beard?”

“That's right!” Volodya burst out laughing. “Like this,” he added, indicating its large bushy shape. “What a memory you have!

“Eventually Solomon came around to the idea on the condition that we hid in the roof of twelve October Street instead. That way he could keep an eye on his family. Hana was keen on thatâshe could fetch anything we needed and let us know when it was safe to come down.