The Marus Manuscripts (35 page)

Read The Marus Manuscripts Online

Authors: Paul McCusker

A

NNISON’S

R

ISK

Manuscript date: September 18, 1927

R

eady or not, here I come!” a child’s voice called out from somewhere behind the shed.

Madina Nicholaivitch giggled and scrambled to find a hiding place. She’d already hidden once behind the well and once in the garage, and now she had to think of somewhere little Johnny Ziegler wouldn’t think to find her.

Johnny shouted, excitement in his voice, “I’m coming, Maddy!”

Everyone called her Maddy now except her grandparents, who still spoke in Russian and called her Dreamy Madina in that tongue. It didn’t matter to them that they’d been living in America for 10 years now. “We will not forsake our traditions, no matter where we live,” Grandma had said.

On the other hand, Maddy’s father, Boris, now refused to speak any Russian. He said he was protesting the Russian Revolution of 1917 that drove them, persecuted and destitute, from their home in St. Petersburg. “We’re in America now,” he stated again and again in his clipped English. “We must speak as Americans.”

“The revolution will not last,” Maddy’s grandpa proclaimed several times a year, especially in October, on the anniversary of the revolution.

“It is now 1927, is it not?” Maddy’s father argued. “They have killed the czar, they have destroyed everything we once held dear, and they are closing our churches. I turn my back on Russia as Russia turned its back on us. We are Americans now.”

So Madina became Maddy and spoke American because she was only two when they came to America. She never really learned Russian anyway, except for odd phrases from her grandparents. Refugees that they were, they’d started off in New York and drifted west to Chicago as opportunities from various friends and relatives presented themselves. Boris had been an accomplished tailor back in St. Petersburg, so his skill was in demand wherever they went. Then they’d heard from a cousin who owned a tailor shop in a small Midwestern town and wanted Boris to join him in the business. They called the firm Nichols Tailor & Clothes, Nichols being the English corruption of their original Russian name, and made clothes for nearly everyone, including the mayor.

Maddy was unaffected by all the changes and upheaval in their lives. She seemed contented and happy regardless of where they were. The world could have been falling apart around her, and she would have carried on in her pleasant, dreamlike way, lost in fantasies like

Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan,

and the many other stories she read at the local library.

She often pretended to be a girl with magical powers in a fairy-tale world. Or she played out a dream she’d been having night after night for the past two weeks. In the dream, she was a lady-in-waiting to a princess with raven black hair and the most beautiful face Maddy had ever seen.

“You must come and help me,” the princess said to her every night in the dream.

“I will,” Maddy replied. And then she would wake up.

She had told her mother about the dream. But her mother smiled indulgently and dismissed it as she had most of Maddy’s fanciful ideas.

Apart from pretending to be in fairy tales, Maddy enjoyed playing games like hide-and-seek with the smaller neighborhood chil

dren. Her mother often said that she would be a teacher when she grew up because she loved books and children so much.

Maddy circled their old farm-style house that had been built with several other similar houses on the edge of town. It had gray shingles, off-white shutters, and a long porch along the front. She ducked under the clothesline that stretched from the porch post to a nearby pole. The shirts and underclothes brushed comfortingly against her face, warmed by the sun. She then spied a small break in the trelliswork that encased the underside of the porch. That would be her hiding place, she decided—under the porch.

She pressed a hand down on her thick curly, brown hair to keep it from getting caught on any of the trellis splinters and went only as far under as she dared, to the edge of the shadows. The dirt under her hands and bare legs was cold. She tried not to get any of it on her dark blue peasant dress, which her father had made especially for her. She could smell the damp earth and old wood from the porch. In another part of the garden, she heard her little brother squeal with delight as their mother played with him in the late-summer warmth.

“I’m going to find you,” little Johnny, the boy from next door, called out.

Maddy held her breath as she saw his legs appear through the diamond shapes of the trellis. He hesitated, but the position of his feet told her that he had his back to the porch. Maybe he wouldn’t see the gap she’d crawled through. He moved farther along, getting closer to the gap, so she moved farther back into the shadows and darkness. The hair on her neck bristled. She’d always worried that a wild animal might have gone under the porch to live, just as their dog Babushka had when she’d given birth to seven puppies last year. But Maddy’s desire to keep Johnny from finding her was greater than her fear, so she went farther in.

The porch, like a large mouth, seemed to swallow her in darkness. The trelliswork, the sunlight, and even Johnny’s legs, now moving to and fro along the porch, faded away as if she’d slowly closed her eyes. But she knew she hadn’t. She held her hand up in front of her face and wiggled her fingers. She could see still them.

Then, from somewhere behind her, a light grew, like the rising of a sun. But it wasn’t yellow like dawn sunlight; it was white and bright, like the sun at noon. She turned to see, wondering where the light had come from. She knew well that there couldn’t be a light farther under the porch, that she would soon reach a dead end at the cement wall of the basement.

As she looked at the light, she began to hear noises as well. At first they were indistinct, but then she recognized them as the sounds of people talking and moving. Maddy wondered if friends from town had come to visit. But the voices were too numerous for a small group of friends. This sounded more like a big crowd. And mixed with the voices were the distinct sounds of horses whinnying and the clip-clop of their hooves and the grating of wagon wheels on a stony street.

Crawling crablike and being careful not to bump her head on the underside of the porch, Maddy moved in the direction of the light and sounds. The noises grew louder, and, once she squinted a little, she could see human and horse legs moving back and forth, plus the distinct outline of wagon wheels.

It’s a busy street,

she thought, but then she reminded herself,

There’s no busy street near our house.

The sight inflamed her imagination, and she ventured still closer and closer to the scene.

It’s like crawling out of a small cave,

she thought. Then her mind raced to the many stories she’d read about children who had stepped through a hole or mirror or doorway and wound up in a magical land. Her heart beat excitedly as she thought—

hoped

—that maybe it was

about to happen to her. Perhaps she would get to see something wondrous; perhaps she was going to enter a fairy tale.

At the edge of the darkness, she glanced up and realized she was no longer under the porch. The coarse planks of plywood and the two wheels directly in front of her and two wheels directly behind her made her think she must be under a wagon. More startling was that the porch, the trellis, Johnny, and even her house had disappeared.

A man shouted, “Yah!” and snapped leather reins, and the wagon moved away from her. She stayed still, afraid she might get caught under the wheels, but they didn’t touch her. In a moment she was crouched in an open space, sunlight pouring down onto her. People were crowded around, and she stood up with embarrassment on her face, certain they were wondering who she was and where she’d come from.

A man grabbed her arm and pulled her quickly into the crowd. “You’d better get out of the road, little lady,” he warned. “Do you want to get run over by the procession?”

Besides that, no one seemed to notice her. But she noticed them. Her eyes were dazzled by the bright colors of the hundreds—maybe even thousands—of people lined up on both sides of the avenue. Trees sprung out from among them like green fountains. Tall buildings stood behind them with enormous columns and grand archways. Maddy blinked again. The colors seemed too bright somehow, much richer than the colors she was used to seeing. Then she smiled to herself: They looked just like the colors in so many of the illustrated stories she’d read.

She noticed that some of the people clutched flags and banners, while others held odd-looking rectangular-shaped hats to their chests, and a few carried children up on their shoulders. What struck Maddy most were the peculiar garments everyone wore. The

women were in long, frilly dresses, not unlike Maddy’s own peasant dress but far more intricate in their design, billowing out at the waist like tents. The men had on long coats and trousers that only went to just below their knees. The rest of their legs were covered with white stockings. On their feet they wore leather shoes with large square buckles. The men had ponytails, she noticed, and hats that came to three-pointed corners.

The scene reminded her of the last Fourth of July, when she had stood along Main Street with the rest of the townspeople for the big parade, followed by fireworks and picnic food in the park. Some of the people in that parade had dressed the same as the people she saw now. It was the style of clothes worn when America won its independence.

Unlike the parade back home, however, this parade didn’t seem very happy. Most of the people stood with stern expressions on their faces. A few looked grieved. Several women wiped tears from their eyes. Maddy suspected she had formed the wrong impression of what she was seeing. Maybe it wasn’t a parade; maybe it was a funeral procession.

“Did someone die?” Maddy asked the man who’d pulled her from the street.

He gazed at her thoughtfully and replied, “Our nation, little lady. Our nation.”

A regiment of soldiers now marched down the avenue. The men were dressed in the same outfits as those in the crowd, but all were a solid blue color, and they had helmets on their heads and spears or swords in their hands. They broke their ranks and spread out to the edge of the crowd.

“The king is coming, and we want you to be excited about it,” one of them said gruffly.

“He’s not

our

king!” someone shouted from the thick of the crowd.

The soldier held up his sword menacingly. “You can be excited or arrested,” he threatened. “The choice is yours.”

The soldiers moved off to stir up other parts of the crowd. Across the avenue, a fight broke out, and Maddy watched in horror as three soldiers began to beat and kick a man they’d knocked down. They dragged him away while the rest of the soldiers stood with their swords and spears at the ready.

What kind of parade is this,

she wondered,

where the people are forced to enjoy it or be beaten?

As if to answer her question, Maddy remembered the stories her father told of the Russian revolutionaries who demanded that people parade and salute even when they didn’t want to.

Halfhearted cheers worked their way through the crowd as a parade of horses approached and passed, soldiers sitting erect on their backs, swords held high in a formal salute. Then a large band of musicians with woodwinds and brass instruments came by, playing a lively song of celebration. Next came several black open-topped carriages, each with people dressed in colorful outfits of gold and silver that twinkled in the sunlight. The men wore white shirts with lacy collars. The women wore hats with brightly colored feathers sticking out of the backs. They waved and smiled at the crowd.

Maddy noticed one man in particular who seemed almost as unhappy as some of the people in the crowd. He had a pockmarked face, unfriendly eyes, a narrow nose, and thinning, wiry hair. Unlike the rest of the parade, he didn’t wear a colorful jacket but one of solid black—as if he, too, were mourning something. Occasionally he lifted his hand in a wave, but Maddy was struck by the look of boredom on his face. It seemed to require considerable effort for him to be pleasant to the crowd.

At the end of this particular procession came the largest carriage

of all. The carriage was gold on the outside; its seats were made of a plush, red material. A man sat alone on the rear seat—propped up somehow to raise him higher than he normally would have been—and waved happily at the crowds. He was a pleasant-looking middle-aged man with ruddy cheeks, big eyes, and wild, curly hair.

“I was wondering if he’d wear that stupid wig,” someone muttered nearby.

“It’s no worse than that coat,” someone else commented.

The man’s coat displayed the colors of the rainbow and had large buttons on the front. Maddy smiled. It made him look a little like a clown.

“I can’t bear it,” a woman cried as large tears streamed down her face. Even with the tears, she waved a small flag back and forth.

“What’s wrong?” Maddy asked the woman. “Why are you crying?”

The woman dabbed at her face with a handkerchief. “Because it’s the end of us all,” she replied with a sniffle.

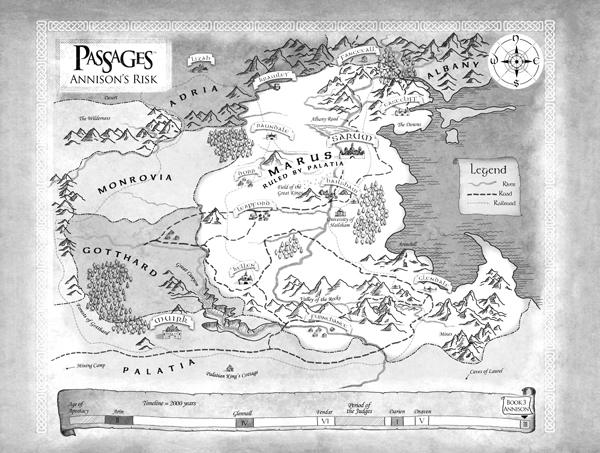

“Aye,” an elderly man behind her agreed. “When the barbarians parade down the streets of Sarum, it’s the end of Marus.”