The Martian Race (30 page)

Authors: Gregory Benford

Tags: #Science Fiction, #Fiction, #General, #Space Opera, #Adventure, #Interplanetary Voyages, #Mars (Planet)

Then came an anxious Axelrod. His yachting jacket was a bit rumpled and he looked worried.

“Your coverage was aces on the Airbus meeting. Got to let you know, though, that all of us here want to get your impressions of what they're planning to do. Any chance they'll finish their recon in a few months? I mean, and get all that ice melted and into their tanks? Raoul, Viktor, the engineers here need your assessment of their capability.”

“How can?” Viktor talked back uselessly to the screen. “We see no gear, no hoses or mining equipment.”

“Tell him to ask his spy guys for that,” Marc joined in.

“—and keep track of how they're setting up. I mean, are they uncorking one of those inflatable habitats we heard about?” Axelrod flashed on the screen photos of trials done with blowup habs, one deployed in orbit.

“Never get me in one of those,” Raoul said. “No radiation shielding.” He had been strict about sandbagging the hab roof on the first full day after their landing. He had even strung more over the lip, to get more coverage. Viktor had remarked to Julia that after all, Raoul was hoping to have more children.

“—and their supplies. Point is, my guys, we're wondering down here if Airbus would maybe do an end run around you. Take off maybe a month or two after you do, but catch up on the return. With enough water, the engineers tell me, they could.”

“Impossible,” Raoul said. “They might have the tank volume, but mining that ice, no. It's a big job.”

“—so we're depending on you to fill us in on everything you see. Go over there, sniff around. Invite them to the hab, big dinner and all. Maybe give them the rest of your booze, see if that loosens some tongues. I'd say, get them off by themselves for that, so they're not under Chen's watchful eye alla time.” Axelrod smiled shrewdly. “See, we're putting out the story that we welcome these latecomers and all. But I smell a rat.”

“He's off-base,” Raoul said.

“True,” Viktor said. “They cannot do all the Accords want, plus make their water reaction mass. Not in few months.”

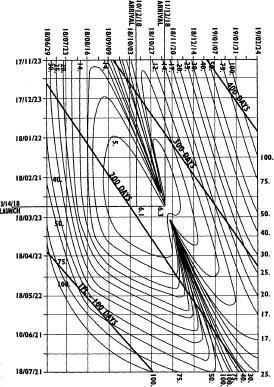

But Axelrod wasn't nearly through. On the screen popped the “pork chop” plots that showed the orbitally ordained launch windows. A big broad spot at the center was the minimum-energy zone. The window was broad, but its edges steep. Just above the spot was a high ridgeline when the energy costs became huge.

A glance told the story: Leave Mars between late January and late March, the dates laid out at the bottom. For these there were orbits for which the energy required to reach Earth was at the absolute minimum. On the left-hand axis were the arrival times on Earth.

“Now, I know you got all this in mind, Viktor, but just lemme see if I'm right here—”

Deciding on a trajectory was in principle simple. Pick a launch date, draw a straight line up into the minimum-energy spot. Depending on exactly which long ellipse Viktor chose, there were different arrival dates at Earth. Draw a horizontal line across the contours to the left-hand axis, tell your loved ones when to expect you in their sky.

“—if I'm readin’ this right, you guys could launch right now and hit damn near the minimum. The contour at January 22, in a couple days, is just a bit higher than the absolute minimum. I read it to be eight kilometers per second of velocity needed. That's versus waiting for the bargain rate on March 14, uh, 6.1 kilometers per second. Now, I know that's not a minor difference. My guys tell me so we're talking maybe seventy-five percent more fuel needed. Not a small order.”

“Energy goes as the velocity squared. You bet is not small,” Viktor said.

“Impossible,” Raoul said flatly.

Axelrod came from a business culture where much could be bought with smiling self-assurance, Julia realized. He was emphatically not a scientist. Deep down, she suspected, he believed that nature could be cajoled into behaving differently if you just found the right approach. He looked grave, then earnest, then respectful—the same sort of lightning-quick repertory she had seen from him in their first solo meeting. She did not doubt that he genuinely felt all those things, either. She had watched him carefully for years now, under the unique need to fathom his true meaning when she could not immediately interrogate him.

Finally, he beamed with renewed confidence. “But somewhere between now and March 14, there's a place where you guys can launch. I dunno where. I leave that to you.” He leaned toward the camera, arms crossed. “But as soon as you can get off, do. Beat Airbus back, if they're planning to try a smash-and-grab operation. Hell, you get home quicker, anyway!”

Raoul froze Axelrod's confident smile. “So he has learned some orbital mechanics.”

“Not very well,” Viktor said. “Those total flight lengths, the diagonals—they show even Axelrod that if we leave earlier, we take more time.”

Marc chuckled. “Maybe he thought we wouldn't notice?”

“No, I doubt that,” Julia said. “He's not a detail thinker.”

“You got it,” Marc said.

“He's hiding a lot of anxiety,” Julia said.

“Has thirty billion dollars on the table,” Viktor said.

“So he probably figures the earlier you leave, the sooner you get there,” Raoul said. “He didn't notice that the earlier launch dates are all further above the ‘200 DAYS’ diagonal.”

“We leave earlier, take longer, arrive little earlier,” Viktor pondered.

“How's our incoming velocity?” Raoul said. “Can't read that from these pork chop plots.”

“Will have to check,” Viktor said. “All would bring us in with small speed. Between them all, is maybe one kilometer per second difference.”

“Any trouble with our aeroshell?” Raoul pressed him.

Viktor shook his head thoughtfully. “No, is rated high. We can burn off the delta vee easily. Like coming back from moon almost.”

“Okay then,” Raoul said decisively. “We can do what he wants.”

“Not so fast,” Viktor said. “Matter of margin here. I like to have extra fuel, maybe twenty percent.”

Raoul said, “That's a lot—”

“For ship standing on Mars for years, not so much,” Viktor shot back.

Raoul glanced at the others. “We could drop our mass load some.”

“Not much,” Marc said. “It's just food, water, mostly.”

“Personal effects, it's maybe enough to make a one percent difference,” Raoul said.

“If drop all, could be,” Viktor said.

Julia could tell Viktor was sitting back, letting the talk run to see what would come out. Even she could not read him all the time. Maybe that was the signature of a good captain. “I've got very little disposable.”

“The most we have, masswise, is Marc's samples,” Raoul said, not looking at Marc.

“Hey, the Mars Accords

require

those,” Marc said.

“Not all of them,” Raoul said.

“Damn near.” Marc stood up. “I'm not compromising—”

“No point to argue,” Viktor said smoothly. “I set safety margin. Marc, I need the total mass you're carrying back anyway.”

Marc bridled. “You're not thinking—”

“Right, am not thinking. Just counting. Let me see total mass from everybody.”

“You're going to shave the margin that close?” Julia asked wonderingly.

“I think about it.”

“Next we'll be discussing Raoul's big old coffee mug,” she said in an attempt at lightness.

It failed badly. Raoul's face clouded.

Julia said, “Just kidding. What bothers me about this talk is that I've got plenty to do on the vent life. I need a month, easily, to—”

“Plenty of time to do that on the trip home,” Raoul said.

“I can't, not and keep to the bio protocols. I'd have to work in the little onboard glove box, and there's not nearly enough room in there to carry out my experiments on—”

“Science isn't the issue here,” Raoul said. “Let ‘em do that Earth-side, then.”

“The samples will die! I don't know if they'll even survive tonight—”

“If they don't, that settles the issue, then,” Raoul said.

She made herself take a deep breath. “It does not. I might want to go back down there, do more—”

“No more trips,” Viktor said. “Raoul is right, science over.”

“It's too early to say that! I—”

“It is too late,” Viktor said calmly, turning to her. “Game now is get back fast.”

“If we leave the big questions unanswered—”

“Airbus can answer,” Viktor said. “They have time.”

“But, but—” She could not see a way around him. “Look, let's hear the rest of Axelrod's message.”

This was pretty transparent, but then, they did not know that she had specifically sent Axelrod a quick question about when to announce her discovery, tacked onto the Airbus reception footage.

Sure enough, Axelrod quickly moved to answer. After a little cheerleading, he said, “Oh yes, Julia. I'm not going to go anywhere with the life story. Sure, it's huge, but I've got lawyers on my tail here. The Planetary Protocol people, they'll go ballistic when we announce. I want to do that

after

you guys have lifted off. No stopping you then—and I think that's what's at stake here. Somebody—hell, maybe the Feds—will slap an injunction on me, try to stop you coming back at all. I mean it. You got no idea what this circus is like, back here.”

“Oh no,” she said weakly.

“—and Raoul, I want your verdict on the repairs, right away. Before you knock off for today. I know you're tired, all of you, been working hard. But we gotta know back here, make plans.” He paused, beamed again. “Plans for your victory celebration, soon as we know the launch date.”

They sat in silence as the screen went gray with static.

Julia fumed. “Damn him. This is the biggest story—”

“He knows the situation there,” Raoul said.

“He is boss,” Viktor said.

“Well, he doesn't control everything,” she said. “I can blow the story any time.”

Raoul's eyes bulged. “What!”

“Tell my parents, just let it slip. They'll know what I mean.”

“You wouldn't,” Raoul said.

“I would.” She put more confidence into her tone than she felt. “Axelrod can't suppress news this big! We'll have a devil of a time explaining why we stalled.”

“He is boss,” Viktor said simply.

“If he told you to dump your gemstones, would you do it?” she said sharply.

Viktor looked affronted. “Is my personal mass.”

“I'd say we may have to put all our cards on the table,” she said in what she hoped was a calm manner.

“Hey,” Marc said, “let's cool this off a little.”

“I'm tired,” Raoul agreed. “Got to call Earthside and report, too.”

She tried to think of a way to smooth matters over. Better not let everybody sleep on unresolved issues. “How is it going?”

“Pretty well.” Raoul smiled. “I'm replacing all the seals I can.”

“Can?” Marc pressed.

“I'd like to replace every one. They've been standing in that damned peroxide dust for years. Impossible to tell if they have micropore damage, not without putting every square millimeter under a microscope. The temperature swings stress the material, crack it, peroxides get in, eat away—a nightmare.”

For Raoul this was a long speech, especially lately. Julia said, “They only have to work once.”

“Right, one clean shot. That's all I'm asking for.” Raoul smiled wanly.

Viktor said, “As soon as I say we can lift, we go. Okay?”

There wasn't any real doubt. He was captain. But Julia seethed.

JANUARY 22, 2018

T

HEY SPENT ANOTHER DAY IN HARD, EARNEST LABOR

. R

AOUL AND

V

IK

tor were refitting every possible seal, testing every valve, examining electrical interfaces, endlessly checking, checking, checking.

There was plenty of gofer work for Julia and Marc. He, however, was more than willing to take some of her chores. That freed some of the day for Julia's greenhouse experiments. Just why Marc was so willing she did not question, though she suspected that his anxiety over the ERV exceeded his interest in the vent mat. Maybe he was trying to help everyone, bridging the growing gap in their interests with his work.

She forgot all that as soon as she stepped inside the greenhouse.

The mat samples were indeed growing. In the mist chamber the pieces had expanded and merged, nearly covering the available floor space. Where they touched they blended seamlessly: this was a surprise that hinted at their complexity. Individual bacterial cultures would maintain a perimeter, whereas cultured tissue from higher plants and animals would be expected to blend together. In a few places there was a hint of more complex structures.

She had enough material to start some more sophisticated biochemical tests. She gingerly cut off a piece of the mat, bracing for some kind of reaction. But nothing happened.

She froze, then thin-sectioned tiny pieces of mat for biochemical staining and microscopic examination. Under the microscope the colors showed that the basic constituents of life—proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, nucleic acids—were the same here, or at least close enough to respond to the same simple chemical tests.

“All right!”

This was already a big step. Although the biologists had been betting that Mars life would be carbon-based, no one had known for sure what she would find. Some had speculated it could be silicon-based— even some kind of self-assembling mineral life. But so far matters were a lot less strange.