The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World (29 page)

Read The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World Online

Authors: Holger H. Herwig

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War I, #Marne, #France, #1st Battle of the, #1914

Sir John French sprang into action. He was flummoxed. “I know nothing of this Order,” he petulantly barked out. He turned to Henry Wilson. The latter allowed that he had received Joffre’s instruction during the night, but had not studied it, much less translated it for Sir John. Joffre was livid, but he maintained his customary calm. The atmosphere had turned from ice cold to hostile. Another pained silence followed. Junior officers dared not speak. French and Lanrezac refused to speak to each other directly. When Sir John invited the group to lunch, Lanrezac declined.

62

Charles Huguet, chief of the French Military Mission at GHQ, summarized the conference as having been conducted with “extreme coolness” and “lack of cordiality.” It had “achieved no military result.”

63

Later that night, Huguet informed Joffre, back at Vitry-le-François, that the BEF had not only lost a battle, but “all cohesion.” It would require “serious protection” from the French army before it could reorganize.

64

Joffre moved with alacrity.

65

He enacted General Instruction No. 2, standing up French Sixth Army under Michel-Joseph Maunoury out of VII Corps and four reserve divisions around Amiens. He formally abolished Pau’s Army of Alsace since most of its units had already been sent to Sixth Army. And with another stroke of the pen, he crossed off the hapless Army of Lorraine, sending its infantry divisions to Third Army and its staff to Sixth Army. It was Joffre at his best: decisive, resolute, unflappable.

Colonel Huguet’s reference to a “battle lost” concerned Le Cateau. While the French and British held their desultory discussions at Saint-Quentin, advance guards of Kluck’s First Army had, at dusk on 25 August, attacked the Coldstream Guards of Sir Douglas Haig’s I Corps, withdrawing on the east side of the Forest of Mormal. In fact, Haig had callously disobeyed Field Marshal French’s order to assist British II Corps. He instead prepared to shelter for a few hours in deserted army barracks at Landecries. There occurred several street fights with Kluck’s advance guard that night. This minor, accidental encounter set off near panic at corps headquarters—where Haig’s staff prepared to destroy the unit’s records—and at Saint-Quentin—where French’s chief of staff, Sir Archibald Murray, “completely broken down,” could scarcely be sustained by “morphia or some drug” before “promptly” slipping into a “fainting fit.”

66

Landecries was not Haig’s finest hour. It was one of the rare occasions on which the normally steady Haig became “rattled,” possibly the aftereffects of a severe bout of diarrhea from the night before. Standing on a doorstep, revolver in hand, he cried out to John Charteris, his chief of intelligence, “If we are caught, by God, we’ll sell our lives dearly.”

67

He was spared the sale. The I Corps continued its retreat toward the Aisne River the next morning.

Yet again, the greater danger faced Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien’s II Corps, falling back on the west side of the Forest of Mormal. Delayed by the passage of Jean-François Sordet’s cavalry corps across its line of retreat, II Corps was itself harassed by more of Kluck’s advance guards. It just managed to reach Solesmes, where it found cover under the guns of Sir Thomas Snow’s newly arrived 4th ID. But late that night, Sir Edmund Allenby’s cavalry division (CD) reported that Kluck was closing in on the BEF. Smith-Dorrien decided that his best chance lay in preparing his defenses and then “giving the enemy a smashing blow.”

68

Twice he communicated his decision to GHQ. At 3:30

AM

, he ordered his units to stand their ground on a low ridge running west of Le Cateau.

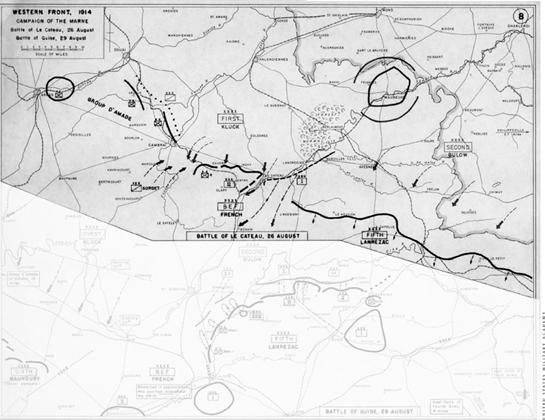

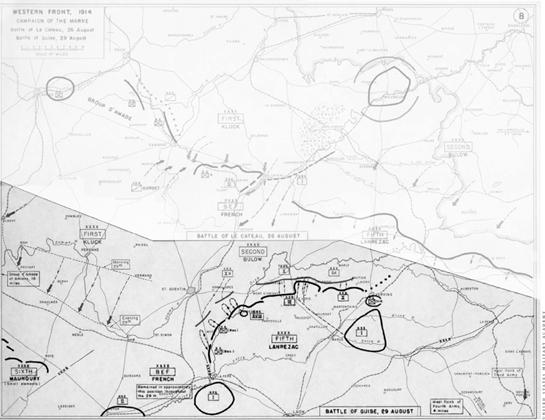

BATTLE OF LE CATEAU

BATTLE OF GUISE

The Battle of Le Cateau coincidentally fell on the 568th anniversary of the Battle of Crécy, where Edward III of England had defeated the far superior army of Philip VI of France. But in 1914, fate favored the stronger battalions. At 6

AM

, the guns of Kluck’s First Army, sited on the heights above the town, unleashed a deadly barrage. At first, Smith-Dorrien’s center managed to hold its own against the infantry assaults of Friedrich Sixt von Arnim’s IV Corps. But on the right flank, left unprotected by Haig’s retreat from Landecries, Ewald von Lochow’s III Corps drove forward to envelop British II Corps. Furious counterattacks failed to repel the Germans, and 19th IB as well as 5th ID seemed threatened with destruction. On the left flank, too, the situation grew precarious as Georg von der Marwitz’s II Cavalry Corps and two infantry divisions of Hans von Gronau’s IV Reserve Corps attacked “Snowball” Snow’s 4th ID. British II Corps was saved from possible annihilation by a timely sortie by Sordet’s cavalry corps against Gronau’s IV Reserve Corps and by an almost suicidal attack by Henri de Ferron’s 84th Territorial Division against Alexander von Linsingen’s II Corps moving up to join Gronau’s units.

In contrast with the brutal offensive infantry assaults supported by massive artillery barrages at Charleroi, in the Ardennes, and in Lorraine, Le Cateau was a battle waged on open and largely treeless fields, in which British riflemen fought from prone positions and rarely had the luxury of digging rifle pits. It in many ways was more like a battle out of the U.S. Civil War or the Franco-Prussian War than the fighting one normally associates with World War I. Still, the British suffered 7,812 casualties at Le Cateau, their greatest battle (and losses) since Waterloo. The next day, gray and gloomy with heavy down-pours, the commanders of two exhausted battalions surrendered rather than offering battle near Saint-Quentin.

69

By 28 August, intensely hot again, the BEF had put the Oise River between itself and the pursuing Germans. Even the ever-optimistic Henry Wilson was seen at the new headquarters in Noyon mumbling, “To the sea, to the sea, to the sea.”

70

French communications at Belfort intercepted Wilhelm II’s ebullient radio message to the troops: “In its triumphant march, First Army today approaches the heart of France.”

71

Still, Le Cateau was a bitter pill for Kluck to swallow. For a second time (after Mons), he had inflicted a tactical defeat on the British, but at great (unspecified) cost to his own forces and delay in the great sweep through northeastern France. And for a second time, due to poor intelligence and reconnaissance, he had failed to “achieve the desired annihilation.”

72

LE CATEAU STIRRED JOFFRE

to still more feverish activity. Around 6

AM

on 27 August, he dispatched an urgent appeal to Lanrezac, reminding the commander of Fifth Army to launch the counterattack against the Germans that Joffre seemingly had promised French at the conference in Saint-Quentin the day before.

73

The situation had grown more critical since then, given that Hausen’s Third Army had crossed the Meuse at Dinant. Joffre called for an immediate strike northwest from the region of the Oise River between Hirson and Guise. Yet again, Lanrezac prevaricated. He preferred to withdraw another twenty kilometers south, there to regroup, and then to attack from around Laon. All the while, Huguet bombarded Vitry-le-François with ever more dire reports concerning the British army.

74

By early afternoon on the twenty-seventh, it had evacuated Saint-Quentin, exposing Lanrezac’s left flank. At 5:45

PM

, Huguet reported that the BEF’s situation was “extremely grave” and that its retreat threatened to turn into a “rout.” In a final communiqué later that evening, he informed Joffre that after Le Cateau, two British infantry divisions were “nothing more than disorganized bands incapable of offering the least resistance,” and that the entire BEF was “beaten, incapable of a serious effort.” At 8:10

PM

, Joffre gave Lanrezac a direct order to attack toward Saint-Quentin.

It was a bold plan. Bülow’s Second Army was moving in a southwesterly direction—Karl von Einem’s VII Corps and Guenther von Kirchbach’s X Reserve Corps were approaching the British near Saint-Quentin—and thus offered an inviting flank for a counterattack. Of course, Joffre also knew that the plan was risky because he was asking much of a battered and exhausted army that had just marched almost three hundred kilometers first up to and then back from the Sambre. Fifth Army would have to execute a ninety-degree turn from northwest to west—while facing major enemy forces. Hence, Joffre dispatched one of his staff officers, Lieutenant Colonel Alexandre, to Lanrezac’s headquarters at Marle to monitor the attack. Unsurprisingly, neither the professor from Saint-Cyr nor his chief of staff, Alexis Hély d’Oissel, was amused by being lectured by a junior officer. Lanrezac sent Alexandre back to Vitry-le-François with a brutal peroration: “Before trying to teach me my business, sir, go back and tell your little strategists to learn their own.”

75

Joffre’s new deployment plan must have reminded Lanrezac of his recent trials and tribulations in the Battle of Charleroi. There, Fifth Army had been boxed into the triangle formed by the Sambre and Meuse. Now he was being asked to fight in a similar triangle around Guise, where the Oise River, after flowing east to west, turns sharply southwest. More, he would have to divide his forces: While Émile Hache’s III Corps and Jacques de Mas-Latrie’s XVIII Corps would drive west against Bülow’s formations harassing the British around Saint-Quentin, a single corps, Gilbert Defforges’s X, would have to secure the northern front toward Guise as well as to cover Fifth Army’s right flank and rear. That would leave only Franchet d’Espèrey’s I Corps in reserve.

76

At 9

AM

on 28 August, Lanrezac had a not-unexpected visitor: Joseph Joffre. The chief of staff was “shocked” by his commander’s physical appearance: “marked by fatigue, yellow complexion, bloodshot eyes.”

77

In what both officers later admitted was a “tense and heated” meeting, they exchanged views. Lanrezac, without informing Joffre of the dispositions he had made during the night to realign his corps according to GQG’s new design, launched a biting attack on Joffre’s overall strategic plan and reminded him of the great fatigue of Fifth Army and the overwrought “nerves” of some of its commanders. Joffre, fully aware that he could not afford either militarily or politically to have the BEF crushed on French soil, lost his customary calm. He exploded. “His rage was terrific,” Lieutenant Edward Spears, British liaison officer with French Fifth Army, recorded. “He threatened to deprive Lanrezac of his command and told him that he must obey without discussion, that he must attack without his eternal procrastination and apprehensiveness.”

78

When Lanrezac coldly countered that he possessed no written orders, Joffre sat down, seized paper and pen, and provided same. “As soon as possible, the Fifth Army will attack the German forces that were engaged yesterday against the British Army.”

79

By the time the story of the stormy meeting made the rounds in the seething political cauldron of Paris, President Raymond Poincaré noted in his diary that Joffre had threatened to have Lanrezac “shot” if he “disobeyed” this direct order.

80

A request that the BEF join Fifth Army’s attack was readily accepted by Haig—but immediately rejected by Sir John French, who “regretfully” informed Huguet that his “excessively fatigued” troops needed 29 August to rest.

81

Huguet was shocked to learn that the field marshal was planning a “definite and prolonged retreat” south of Paris.

82

Lanrezac was incensed.

“C’est une félonie!”

reportedly was his kindest comment on Sir John and the British.

83

Lanrezac counterattacked out of the triangle of the Oise around Guise in a thick mist at 6

AM

on 29 August.

84

Yet again, he squared off against Bülow. Yet again, the weary soldiers of French Fifth Army and German Second Army were asked for another Herculean effort. Yet again, the terrain was miserable: woods and brush, ravines and streams. Yet again, Paris was the prize. And yet again, both sides had a different name for the battle: Guise to the French and Saint-Quentin to the Germans.